Anglican Section H, Memorial 19/509

Straw Bonnet Maker

Kindly Supplied by Clare Spicer, Hilary Southall and Jill Trethewey 28/01/2021

Jane was born in 1820 in Bridgwater, the middle child of eight siblings. She was baptised on the 4th of March 1820 in St Mary’s Church. Her father was George Gywther, a Welsh merchant seaman from Tenby in Wales, and her mother was Emma, or Amy nee Woolven, born in Brighton, Sussex. George and Emma were married in Bridgwater in 1810, a port where many mariners and their families settled.

Jane’s mother Emma would have taught her daughters to sew from a very early age, and at least two of her daughters used their needlework skills to find work. In the mid part of the 19th century there was a small straw bonnet industry in Bridgwater. This was a separate business from other milliners and hatters working in the town, and employed two different sorts of specialist skills – straw plaiting and straw bonnet/hat sewing.

Census records show that there were straw plaiters working in Bridgwater, who would produce the straw plaits or braid used for bonnets. Jane could have learnt how to plait as a young girl, but it is unlikely as she was able to sign her name, showing that she had been educated. Her father George earnt enough as a mariner to pay a few pennies each week for his children to go to school. Straw plaiters, usually female, would start their training at the age of two years old. They learnt to split and plait straw into intricate braids, using different patterns and number of strands. By the time a child was three or four years old, they were a fast enough plaiter to earn an income. A plaiter would plait continuously, walking around with their bundle of straw under one arm. There was little or no time for any other activity, such as education or housework.

Jane probably learnt how to sew the straw bonnets, either from her mother, or from an experienced maker in the town.

By 1841, Jane, aged 21, was working as a bonnet maker and living with her parents in St Mary Street in Bridgwater. Also there was Jane’s older brother George, 27 a cabinet maker, and younger sisters Kitty 15 and Emma 12. Jane’s older sisters Sarah and Mary Ann had already married and were living with their husbands.

Jane was very likely working at home, probably buying in the straw braid, stitching and then selling the completed bonnets, either to a milliner to decorate, or selling them herself at a market. Alternatively she might have been selling them to a middle man, such as the wholesaler in Bristol, James Hill, who regularly advertised in Bridgwater, selling straw plaits, and who would probably have sent a representative to Bridgwater to buy the completed bonnets as well. There were more than a dozen other specialist straw bonnet makers in Bridgwater during the 1840s.

During the 1840s, life began to change for Jane’s other siblings. Jane’s brother George married Margaret Johns in Bristol in 1842, and they moved away from Bridgwater to Tenby in Wales. Jane’s married sister Mary Ann died in 1845 aged only 29, leaving her husband a widower, but her only child had already died. By 1846, Jane’s father George had bought a freehold house with a garden in Friarn Street, Bridgwater, this must have been a bigger house, able to accommodate growing families. Jane’s younger sister Kitty married John Rogers in Bridgwater in 1847, and the new couple moved in with George and Emma Gwyther in Friarn Street.

In April 1851 George, now a master mariner, was away sailing, but Jane was still living with her mother Emma and younger sister Emma. Jane was a straw bonnet maker and Emma a milliner. Bonnets at this time were highly decorated with ribbons and flowers, so Emma may have been lining and trimming Jane’s bonnets ready for sale, or working for one of the milliners in town.

These are fashionable bonnets, but there would have been a large demand for plainer, cheaper bonnets as well. Women did not like to go out without some kind of head covering. The shape was the same for straw or fabric bonnets.

Read more about making a straw-bonnet and see a photo at the end of this biography.

Also living with George and Emma in 1851 were Jane’s younger sister Kitty, Kitty’s husband John and their two small sons. However, Kitty and John soon moved out to live in St Mary Street.

In 1854, Emma married Jeffrey Denman in Bridgwater, leaving Jane the only sibling still unmarried.

Jane met a young clerk, William Dyment, somewhere in Bridgwater, and on the 13th of May 1856 they were married in Bedminster, Somerset, by licence. Their entry on the marriage register is puzzling, as both gave their age incorrectly. William claimed to be 21 when he was only 20, so technically a minor. William’s father Isaac had died in 1849, and his mother Eliza had re married and was living in Swansea, so perhaps there was no one available to give William the official permission to marry. Getting married by licence away from Bridgwater enabled the new couple to be more discreet. Jane was 36 and was embarrassed enough by their age difference to take 12 years off her age on the marriage register, claiming to be 24. Both were born before the introduction of official birth certificates, but William must have been aware that Jane was quite a bit older than him. However, on every census after this, Jane claimed to be significantly younger than she really was. Jane was able to sign her name on the register, and her sister Kitty was a witness. After their marriage, William and Jane moved in with her parents in Friarn Street.

Jane and William had a son called George William in 1859, and a daughter Eliza in 1861.

In 1861, Jane and William, together with their two young children were living with her parents in Friarn Street. William’s younger brother George Dyment was also with them, so the house was busy and full. Jane’s mother Emma would have been able to help with the children, and so Jane was able to continue to work as a straw bonnet maker. Perhaps they were saving up for a house of their own.

Jane’s father George died in early December 1868, aged 79, he was buried in the Wembdon Road Cemetery in Anglican plot 2 C 47. George’s wife Emma continued to live in the Friarn Street house, sharing it with her grandson George Gwyther and a couple of lodgers.

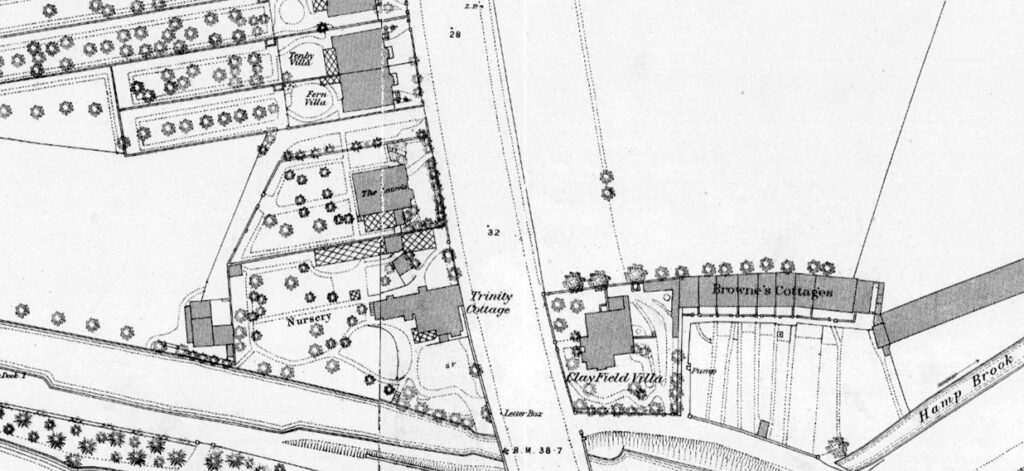

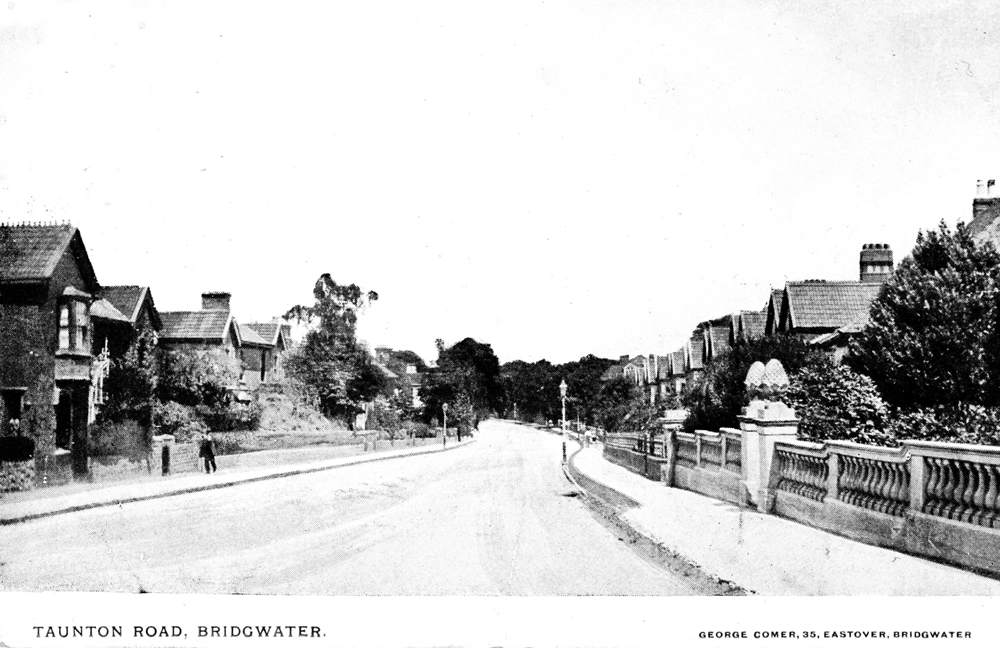

By 1871, Jane and her husband William Dyment were living at 11 Taunton Road, Bridgwater. Jane was only admitting to the age of 42, although she was in fact 51. William was at home at the time of the census, although by now his occupation was described as commercial clerk and traveller. He would have been away from home quite frequently, sometime on long trips, so Jane would have got used to coping on her own. Their children, George aged 12 and Eliza aged 10, were both at school.

There followed a year of loss for Jane. Her younger sister Kitty died in May 1872, aged 48. Ten months later Jane’s mother Emma died in March 1873, followed only one month later by Jane’s elder sister Sarah in April 1873.

Jane and William were still living in Taunton Road in 1881, and William was still travelling as a representative for his employers, cheese factors Thompson and Collins. Their son George was away from home for that census, but Eliza, aged 20 was there. Eliza had completed her education by this time, and was helping her mother at home.

In 1891, Jane and her family were living in Taunton Road, and they had called their house Tenby Villa, perhaps to remember where Jane’s father came from. William was described as a cheese factor, and he had been accepted as a partner at the firm of Thompson and Collins, so their income should have increased, but they continued to live fairly modestly. Jane’s son George 32, was working as a clerk to a cheese factor, no doubt working with his father, and daughter Eliza, aged 30, was also still at home. Unusually no servant is shown as living in, but Jane may have had some domestic help coming in on a daily basis.

On the 1901 census, Jane and William’s address was shown as 22 Taunton Road, and their two children were still living with them. At some point after this, the family moved to 26 Taunton Road.

In July 1907, Jane’s husband William died, aged 71. He was buried in the Wembdon Road Cemetery, Anglican plot H19. Jane lived another two years without him but she died in August 1909, and she was buried together with her husband. Even now her true age was not shown, her burial record gives her age as 87, when in fact she was 89. Jane had lived a busy and productive life, earning her own wage throughout her younger life with a skilled occupation, and then looking after her husband and children.

Straw bonnet making

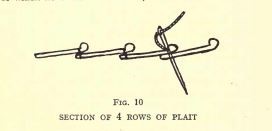

Straw bonnets were made by stitching together narrow braids or plaits of straw. The straw was plaited by a specialist straw plaiter. Her life was one of monotonous, continuous work from early childhood, but it was a reliable and respectable manner of earning an income for poor women and girls. Short split straws would be plaited into a single continuous plait, made to a particular weave. Each plaiter would know a variety of different weaves. Any spare small children of about two or three years old would be taught to clip the loose ends of straw from the completed plait, this was the way the plaiters began their training. When the plait or braid was 20 yards long it would be tied into a bundle for further processing, being bleached and perhaps dyed, before it was passed on to the bonnet maker. Straw could be left a natural colour, or dyed in fashionable shades, and there was always a demand for black, for mourning bonnets.

To make a bonnet out of straw braid, the narrow braid had to be turned into a small circle or oval, called a button. This was stitched firmly in place, and then concentric rows of braid added, one row at a time. Each new row being placed under the preceding row, and stitched down, using a long stitch underneath where it would not be seen, and a very small stitch on top, hidden in the weave of the straw braid.

When the straw braid had been stitched into an oval or circle large enough to form the tip of the bonnet, the maker could change the direction of the work by altering the tension she held the braid in. Pulling tightly would cause the braid to turn downwards, so that the side of the bonnet could be stitched. Pushing on the braid would make it turn outwards, to flare into a brim. The maker needed a lot of skill to stitch evenly and to control the changes in tension smoothly.

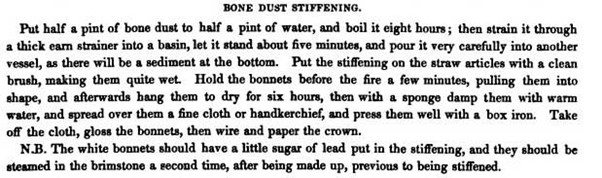

The maker would have a bonnet form or mould, known as a block, and usually made out of wood. As she worked she would regularly check that the bonnet fitted the bonnet block smoothly. When the bonnet was fully formed, it would be damped and stretched on the block. When dry, it would be ironed on the block with a heavy box iron to smooth and fix the shape, and then a stiffening lotion painted over it. Jane may have had to make her own stiffening preparation, or she may have been able to buy it.

Jane and other women of her time required a lot of skill and years of practice to make these beautiful straw bonnets. They were greatly valued by their owners and could be re-trimmed to look new again the next summer. Yet women’s work was hardly mentioned in the official records of her time. You may see surviving examples in specialist museums such as the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, and the Fashion Museum in Bath.