Biographies by Clare Spicer, Hilary Southall and Jill Trethewey, 12/01/2021

Memorial

Through 2019 and 2020 the Friends’ volunteers worked hard to improve the area where two paths cross in the middle of the cemetery, between Anglican sections G, F, J and H. This had focused on the repair of three Dunsford family memorials, the family of John Thomas Upjohn Dunsford, editor of the Bridgwater Mercury, many of whom were tragically killed during a fire in 1883.

Continuing this work, the volunteers now want to improve the other corner of this junction and have earmarked three memorials for repair: the massive Boulting cross on the corner, then the adjoining Hickman cross and Dyment cross. The Hickmans were local chemists/pharmacists, while Dyment were cheese factors, but we’ll return with their stories soon. Here is the story of the Boultings, very kindly research for us by Clare Spicer, Hilary Southall and Jill Trethewey.

If you know of anyone related to these Boultings, or would like to contribute to the set of memorials’ repair, then please get in contact.

Part 1: George William Boulting 1835 -1918, solicitor, Susan Boulting nee Poolman 1838 – 1909, dressmaker, and Amy Boulting 1866-1927, companion to her parents.

George was born in 1835 in Taunton, Somerset. His father, James Boulting, was Bridgwater man, who worked as a plumber, glazier and painter. His mother Elizabeth, nee Frost, was born in Holcombe Rogus, Devon, but some of her family subsequently moved to Taunton and this is where Elizabeth and James got married in 1832. Both James and Elizabeth were able to sign their names on the marriage register, this was relatively unusual for working men and women in the 1830s.

George was baptised in St Mary’s Church Bridgwater on the 23rd of August 1835, and his family remained in Bridgwater after this time. George was actually baptised as William George, and he appears on the 1841 and 1851 censuses under this name, but as an adult he used the name George William.

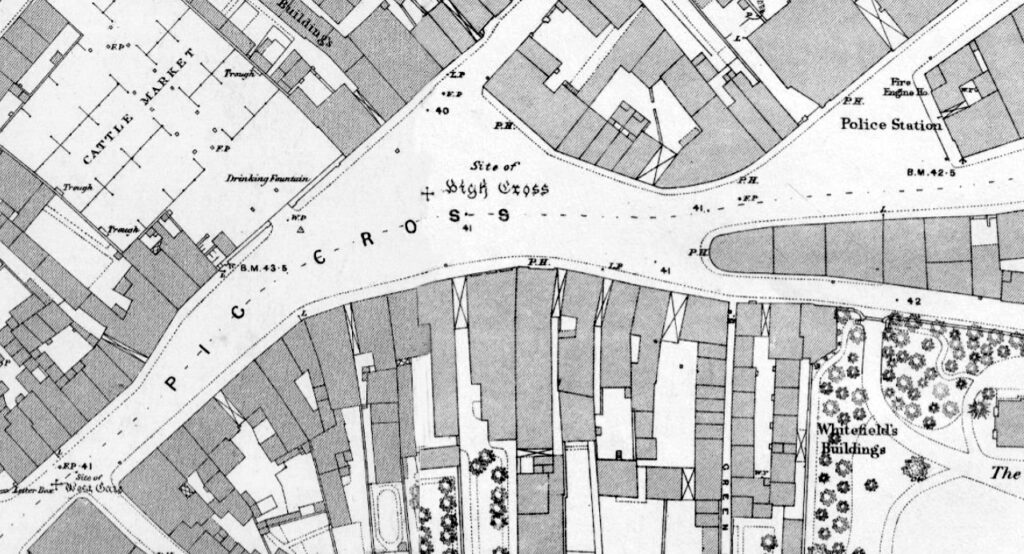

In 1841, James was living in Pig Cross, Bridgwater, with his wife Elizabeth and three children, George aged 6, Jane aged 4 and Fanny aged 2. In 1843, a fourth child, John, was born. By 1851, James and his family were living in Back Lane, James described himself as a plumber, glazier and painter, while his wife Elizabeth was working as a stay maker. The 15 year old George was working as an accountant – this probably meant that he was a ledger clerk, keeping records of expenditure and totalling figures. To do a job like this, George would have had a reasonable standard of literacy, with clear, neat hand writing and a head for figures. The three younger children were all described as scholars. James and Elizabeth must have worked to be able to pay for a good standard of education for all their children, as schooling was not free at this time.

In 1854, George’s younger brother John died, aged only 11. By 1861, James Boulting’s business was prospering. The family were now living in Queen Street, and James was employing a man to help him. The family also employed a 17 year old girl as a house maid. George, aged 25, was still living at home and working as a solicitor’s clerk.

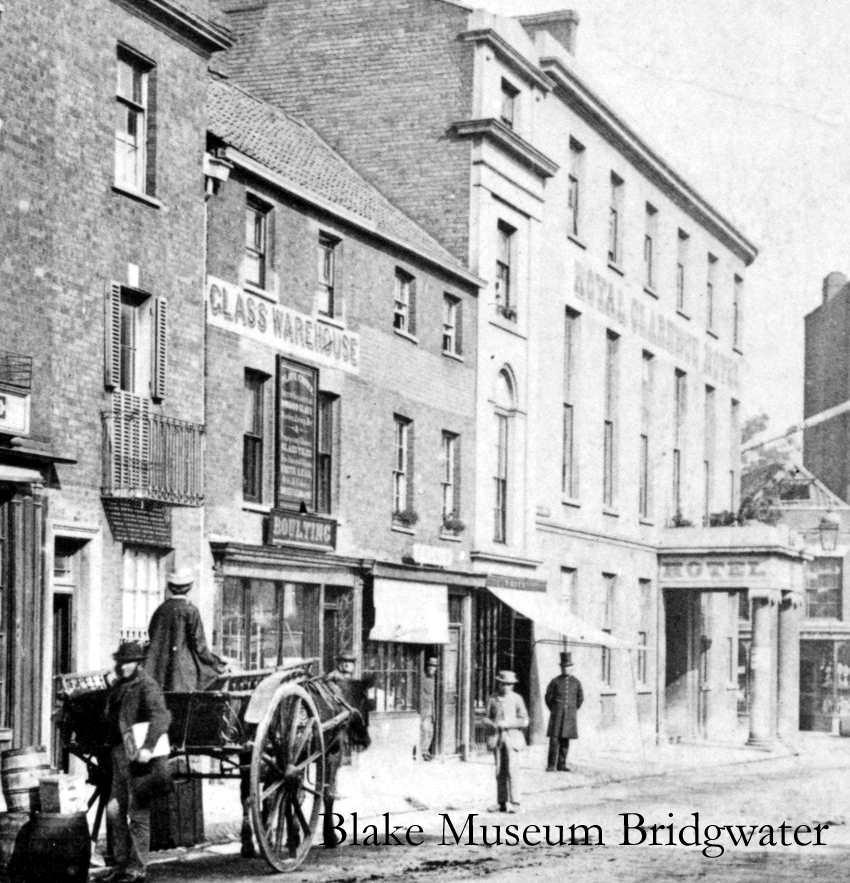

In 1864 James took an important step in expanding his business, by becoming a tenant of a business premises on the High Street, close to the Royal Clarence Hotel. He named this premises the ‘Boulting Glass and China Warehouse’, there was a shop on the ground floor, and the family lived over the shop.

Bridgwater High Street in c.1864/5 showing Boulting's new shop - kindly supplied by the Blake Museum

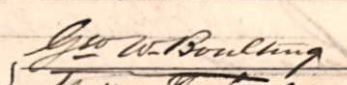

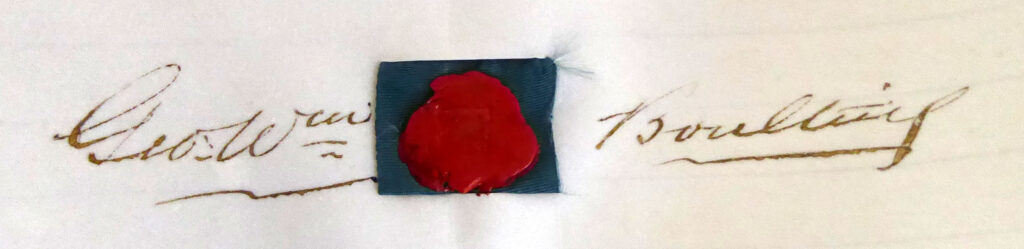

The following year George married Susan Poolman in St Mary’s Church, Bridgwater, on the 20th of July 1865. Susan, aged 26, was the daughter of Joseph Poolman, a master mariner who was deceased, and Jane nee Legge. George described himself as an accountant, and his signature is clear and confident.

George was also a landlord. In 1865 a survey of Eastover was conducted in advance of a potential railway station, and George William Boulting is recorded as owner of a terrace of houses, known as a court, off of Eastover, later called Anstice Place. This consisted of 16 'half-house' dwellings for workers and poorer families, and would have provided George with a steady income. Such courts easily became slums, although there does not seem to be any notable complaints about George in relation to these, or any other properties he may have rented out.

George and Susan had their first child, a daughter Amy, in 1866, and a son the following year. The birth of Eustace George Boulting on the 24th July 1867 was announced in the Bridgwater Mercury. George’s new family were now living in their own home at 4 Alexandra Villas (now Alexandra Road), Wembdon Road, Bridgwater.

Earlier in March 1867, George had become embroiled as a witness in a court case. George was the managing clerk for the Bridgwater solicitor Henry Lovibond. The previous year, acting on behalf of a relative (Robert Lovibond), Henry Lovibond was attempting to reclaim payment of a debt. Henry instructed his clerk George Boulting to distrain goods in payment of the debt. George had to take an inventory of goods at the debtor’s property and use a bailiff to seize goods to cover the amount owed. During this process, a horse was seized that was not actually the property of the debtor. This horse was owned by a third party who happened to be another solicitor called John Vesey, who not surprisingly, objected strongly. Mr Vesey visited George Boulting in his office and was loudly abusive, while George attempted to negotiate with him over a debt of less than £5. George had to give evidence in the subsequent court case, and this case was reported at length in the Bridgwater Mercury, over three full columns. This extraordinary amount of newspaper coverage was perhaps due to the contentious political situation in Bridgwater during the 1860s.

In 1865 one of the Bridgwater Members of Parliament, Henry Westropp had been elected, but this was subsequently contested and Westropp was unseated. This caused considerable division in the town, with some supporting Westropp and others opposing him. A petition was sent from Bridgwater to the House of Commons, objecting to the election of Henry Westropp, and the solicitor Vesey was summoned to the House by the Speaker, to give evidence. The barrister acting for Mr Vesey explained that Vesey was a staunch supporter on Westropp, while the two Lovibonds were equally staunch in their opposition. Vesey’s horse had been seized by the bailiff on the very day he was due to travel to the Houses of Parliament, and his barrister implied that the action by the Lovibond family had been politically motivated. The judge, either in a moment of hilarity or exasperation, inquired if the horse had a vote! The judge finally found in favour of the defendant Robert Lovibond.

George was clearly literate and numerate enough to work as a clerk from the age of 15 in 1851. He probably didn’t go to university, but he would have studied law additionally in his spare time, advised by his employer, and may have travelled to London to take exams. He does not appear on the Register of Articled Clerkships up to 1874, but was described as a managing clerk. Sometimes managing clerks had already qualified as solicitors, but then became a clerk to an established solicitor to gain experience.

A managing clerk had to be capable of working without constant supervision, and working hours were usually between 9 am and 8 pm. A large amount of time would be spent in writing out, or copying documents, and a clerk often wore ‘false sleeves’ to protect his shirt sleeves from ink stains. A clerk would learn to be careful, diligent and cautious, and remain polite to clients at all times. George seems to have kept his temper, even when Mr Vesey was shouting and swearing at him.

Barely had George time to recover from being a witness in the above case in March 1867, when he was involved in April, again as a witness, in a case involving his own family. The Bridgwater Mercury reported the following case from the Bridgwater Police Court on the 13th of April 1867.

‘IMPUDENT ROBBERY. _ John Mole, a little boy aged about twelve years, was charged with stealing 14s 9d, the monies of James Boulting, in High Street, Bridgwater, on the 6th inst. - Mr George William Boulting said he was the son of the prosecutor. On Saturday afternoon last, about 3 o’clock, he went to his father’s shop in High Street, and gave into the hands of his sister Fanny a paper parcel containing £1 18s., in silver coins, with two shillings in copper coins. – Miss Fanny Boulting said that she put the money given her by her brother (the last witness) on the counter, and directly afterwards went into the back of the shop. On her return she found two boys in the shop, one of them the prisoner. When they left she counted the money, and found only £1 3s 3d in silver, and two shillings in copper. – Sergeant Cheriton deposed that on Saturday afternoon he went to Mrs Lake’s shop with Mr Boulting, and saw the prisoner there. Witness charged the prisoner with stealing money from Mr Boulting, and he replied “The other boy took it, and gave me part.” He then took from his pocket 14s 9d, and handed it to witness. He asked Mr Boulting, the prosecutor, to forgive him. – In reply to the Bench, the prosecutor said the prisoner came to his shop to fetch a pound of red lead, and his daughter had left him in the shop while she went to fetch it. On her return she found the other boy there, whose name was Rainey. – George Rainey said he was in the employ of Mr Burrington, carrier, and on Saturday went to the prosecutor’s shop to fetch some weights for his master. The prisoner was in the shop when witness went in, waiting for Miss Boulting’s return, and he told witness what his errand was. Witness did not see the prisoner do anything. – The Chairman (Mr Ford) complimented this witness on the creditable way in which he had given evidence, and said that he left the court without the slightest slur on his character, -The prisoner then pleaded guilty, and was sentenced to seven days imprisonment, and to undergo, in the meantime, ten strokes with a birch rod.”

This seems a harsh punishment for a child now, but was lenient compared to the sentences handed out to even younger children earlier in the century. Red lead was used to provide a primer for outdoor metal, this would probably have been mixed into paint and used to paint railings and gates. James Boulting was obviously selling painting and plumbing supplies from his shop, as well as glass and china.

Together with the birth of his son Eustace in August, 1867 was an unexpectedly eventful year for George Boulting.

On the 1871 census, George was still a solicitor’s managing clerk, and most likely still working for Henry Lovibond. George had moved his family from Alexandra Road to York Buildings, a more central location close to the High Street. This must also have been a larger premises, as George’s wife Susan and his sister Jane Boulting had gone into business together as dressmakers and milliners. In 1871 there were ten people living at George’s address in York Buildings: - George himself, wife Susan, sister Jane Ann Boulting, and George’s children Eustace and Amy Boulting. Also living there were two dressmaker’s assistants and a dressmaker’s apprentice. Additionally there were two female servants, Sarah Bilinger age 21 and Bessy Beer age 14.

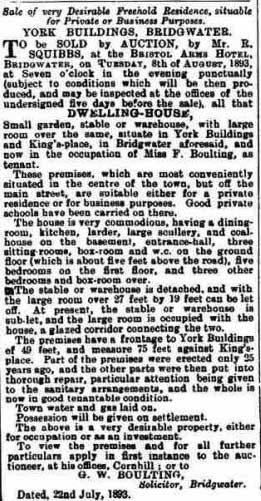

The property where George lived in York Buildings was described in some detail in an advertisement for its sale by auction in 1893. It was described as a desirable freehold residence, suitable for private or business use. It had a frontage to York Buildings of 49 feet and 75 feet to Kings Place. The house had several rooms – a dining room, kitchen, larder, large scullery and coal house on the basement. An entrance hall, three sitting rooms, box room and w.c. on the ground floor (which is about five feet above the road), five bedrooms on the first floor, and three other bedrooms and a box room over. There was a small garden and a stable or warehouse with a large room over it, which was connected to the house by a glazed corridor. The house had town water and gas laid on, and particular attention had been paid to the sanitary arrangements.

This property has now been identified as Maldon House, York Buildings, Bridgwater. It is not clear whether George owned this property, or was a tenant. It was certainly large enough for both business and residential use.

In 1873, George and Susan had their third and last child, a daughter called Florence. In 1876, George’s father James was aged 65 years old, and perhaps he was already unwell. James decided to retire and he gave up the lease on his High Street shop, workshop and home, and moved to West Quay with his wife and daughter Fanny. James died there the following year in February 1877, and is buried in the Wembdon Road Cemetery.

There was a change in George’s professional life around 1876. He was recorded on the Law List as a solicitor, and began to appear in court records, acting either for the defence or prosecution. George’s former employer, Henry Lovibond, had already taken his own son into partnership with him, calling the firm Lovibond and Son. This may have resulted in George deciding to set up on his own account if he wasn’t going to become another partner in the Lovibond practice. George also joined the Freemasons Lodge of Perpetual Friendship in 1878, and was described as a solicitor.

In 1881, George was still living in York Buildings, although the number of people living in his property had grown to 13, divided into two households. George, 45, solicitor, was living with his wife Susan 42, now shown as having no occupation. Also with George and Susan were their three children, Amy 14, Eustace 13 and Florence 7, all listed as scholars, and two domestic servants. Living in the same property but as a separate household was George’s sister Jane Ann Boulting, 43, milliner and dressmaker, with her staff of five dressmakers and milliners.

As a solicitor in a busy market town such as Bridgwater, the bulk of George’s work would be conveyancing, arranging mortgages, drafting wills, collecting rents and either prosecuting or defending minor assault cases and other disputes in the local courts. George’s entry in various directories describes him as a solicitor, commissioner for oaths, clerk to Westonzoyland School Board, and agent to Scottish Provincial Insurance Co. George would probably have employed at least one clerk, and his son Eustace would have occasionally helped him as part of his training, although George would be determined that Eustace got as much formal education as possible.

George also took part in local politics, being on the Bridgwater Division of the Central Conservative Council for the selection of Mr Stanley as the next Conservative candidate in 1886.

In April 1886, George’s widowed mother Elizabeth died, aged 78. By 1889, George and Susan had moved away from York Buildings to live at ‘The Limes’, 43 Church Street, Bridgwater. They were living there in 1891 with their children Amy 24, and Eustace now aged 23 and also a solicitor. Florence was not with her parents, and was probably away studying. A cook and a housemaid were also living with them. George retained his office in York Buildings until he retired.

In 1893, George advertised the property in York Buildings for sale by auction. Kellys Directory of 1895 shows Fanny still living there while working as a milliner and dressmaker.

By 1895, Eustace had moved away from his parents, and was living and practicing as a solicitor in the High Street, Taunton. In 1898 Eustace married Ethel Hall Barker in Liverpool, and they had their first baby, Nora, in 1900. Eustace became a partner in the Taunton firm of Poole and Boulting.

In 1901 George and Susan were still living in Church Street, with their daughter Amy and two domestic servants. Their daughter Florence was working as a teacher in London. George was still practicing as a solicitor, and he must have felt confident that his son Eustace was also well set up for a life of prosperity, but the next few years were difficult ones for the Boulting family.

Eustace and his wife Ethel had their second child in 1901, a boy called Errol George Barker Boulting, but sadly Errol only lived a few weeks. Eustace and Ethel had another baby boy called Geoffrey Noel in 1903, but Geoffrey also only lived for a very short time. They were luckier the following year when they had another daughter, Violet Hilda, who was born healthy.

There was a happier event in 1903 when George’s daughter Florence married Harry Bazell in St Mary’s Church, Bridgwater. Harry was an assistant bank manager in Sunbury on Thames, and the couple settled in London. They didn’t have any children.

In April 1909, George’s wife Susan died, aged 70, and she was buried in the Wembdon Road Cemetery in the family plot H22. George’s daughter Amy kept her father company for the rest of his life. Later that same year, tragedy hit George again, as his son Eustace died in November 1909, aged 42. Eustace left a widow, Ethel, and two little girls.

George’s sisters Jane Ann and Fanny retired together to Bristol, although Jane was in sufficiently poor health to need a nurse living with them. When Jane died in Bristol on the 5th of June 1915, aged 78, George had her body brought back to Bridgwater and buried in the family plot in Wembdon Road Cemetery. After Jane’s death, Fanny returned to Bridgwater and lived with her brother George and niece Amy in Church Street.

George died on the 20th of March 1918 aged 83, and was buried together with his wife in the family plot H22. His sister Fanny only lived another 8 months, and died in November 1918, aged 78, leaving Amy doubly bereft. Fanny was also buried in the family plot in Wembdon Road Cemetery. A grieving Amy moved away from Church Street where she had lived for over 27 years with her parents, to 22 Northfield, Bridgwater. Amy never married, and she died only six years after her father, in November 1924, aged 58. She is also buried with her parents and two aunts in the family plot H22.

George and his sister Jane Ann Boulting lived together in Maldon House for about 20 years, so their family life would have been deeply intertwined. However, their stories have been told separately, in order to give weight to each of their separate businesses.

Part 2: Jane Ann Boulting 1837 – 1915, and Fanny Boulting 1839 – 1918, dressmakers and milliners.

Jane Ann was born in 1837 and her sister Fanny in 1839. Their father James was a plumber and glazier, living with his family in Pig Cross, Bridgwater.

In 1851 their mother Elizabeth was working as a stay maker. She was probably doing piece work at home, hand stitching corsets, which every woman wore at that time. Victorian corsets were elaborate garments with steel stays stitched in, many rows of stitching and a lot of eyelets for lacing. Elizabeth would have taught her two daughters to sew as soon as they could have held a needle, and even while very young, they would have helped their mother by threading needles and picking up pins. Girls soon learnt to sew with a speed and dexterity which can only be envied now. However, James and Elizabeth were keen to get all their children well educated even though this would have to be paid for. In 1851 both their daughters were described as scholars, even though Jane was 14, an age when many girls were already out at work as servants.

Some time between 1851 and 1861, Jane moved to the West End of London to work, and probably her parents had to pay for her to have an apprenticeship, or at least to have paid for her keep while she spent some time learning her job. In 1861, Jane, now aged 23, was living and working as a milliner at 12 Princes Street, Hanover Square London. She was living in the large household of William Priest States, a silk mercer and brewer, and his French wife Maria, who was a milliner. There was a household of 32 people at 12 Princes Street, and while William was importing silk fabric, his wife Maria was running a dressmaking and millinery establishment there. Amongst several other staff, there were eight dressmakers and four milliners living on the premises. Jane was employed as a milliner, and may well have served her apprenticeship there. She would have learnt a lot of sewing techniques as a milliner, but also valuable specialist skills such as using flower irons to make silk flowers to decorate bonnets. Jane got training and prestigious experience in this upmarket West End shop which stood her in good stead for the rest of her life.

In 1861 Fanny, now 21, was living with her parents and working as a draper’s assistant. She was the younger daughter, and so would have been expected to stay at home to help her parents. In 1871 Fanny was still living with her parents. No occupation was shown for her, but the robbery in 1867 (described above) shows that she was running the High Street China and glass shop while her father was out at work.

By 1871, their brother George was living with his family in Maldon House, York Buildings, Bridgwater, and Jane had moved back to Bridgwater to live with him, and set up a dressmaking and millinery business with George’s wife Susan. Maldon House was large and very centrally situated, an ideal location to attract customers. As well as working in the business themselves, Susan and Jane were employing Eliza Allen age 21 and Ellen Wattle age 19, as dressmaker’s assistants and Emma Sellick age 16 was an apprentice.

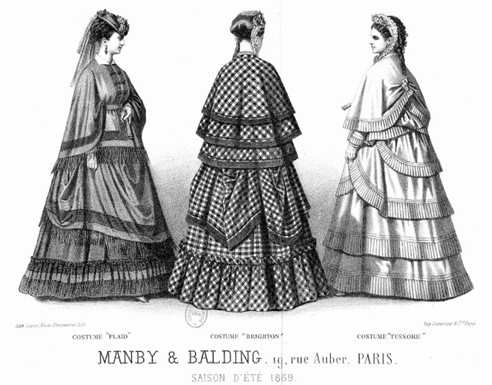

Jane’s West End experience meant that she would be able to advise their customers on the latest fashions and colours, and give some glamour and elegance to the dressmaking and millinery business she and Susan were running. Jane started her training surrounded by luxurious silks, but much of her work in Bridgwater would be using more practical fabrics such as wool, cotton and linen. Artificial dyes were developed during the second half of the 19th century, making much brighter colours available.

Although affordable domestic sewing machines were available at this time, with four seamstresses and an apprentice working, it is likely that a lot of hand sewing was being done. Crinolines were going out of fashion, but women’s dresses were still very voluminous, with lots of frills, flounces and pleats. This would mean yards of fabric to be hemmed, seamed and gathered, and innumerable button holes and eyelets to be hand stitched. Much of their work may have been doing alterations, remaking old dresses to look more up to date, and there were also many undergarments to be made, corsets, chemises, hooped petticoats and drawers, as well as night dresses and outer wear such as cloaks and capes. Jane would have been making stitched hats and frilled caps, bonnets were out of fashion, although older ladies may still have worn theirs. A fashionable hat was much smaller, worn on top of the head and with a lot of elaborate trimmings.

When Susan, Jane and their sister Fanny walked out to go to church, they probably would have taken care to wear their smartest, most fashionable clothes and hats, to advertise their sewing skills and fashion sense.

In 1881 Jane was still living in the same house as her brother George, but was now shown as the head of her own separate household. George’s wife Susan was no longer working as a dressmaker, but Jane was employing Lilian Oliver 22, Julia Hodder 21, Lydia Sellick 19 and Annie Norman 17, all assistant dressmakers and Minnie Keirle 17, milliner. It looks as though Jane had to keep recruiting and training young girls as dressmakers, no doubt they left when they got a better offer of work, or to get married. The fact that the young women were ‘living in’ meant that they were not paid so much, and were expected to work long hours. Fanny was living with their widowed mother in West Quay, but was also working as a dressmaker, no doubt together with her sister Jane.

The communal family life of the Boultings began to change during the late 1880s. Their mother Elizabeth died in 1886, and Fanny moved in with her sister Jane. By 1889, George, Susan and Amy moved out of Maldon House to 43 Church Street, although George retained an office in York Buildings. In Kelly’s Directory 1889, Jane and Fanny are listed together as dressmakers and milliners, but there was a change by 1891. Jane, although aged only 53, was shown as ‘retired’. Perhaps her health was not good, or she was having trouble with her eyesight, a common problem for dressmakers and milliners, working long hours with inadequate lighting. Possibly Jane may simply have felt that she could afford to retire now, as Fanny was free to take on the business. Fanny was now shown as the head of the household, and she was named as the tenant of Maldon House. Jane was living with Fanny as a boarder, but the sisters still had two dressmaking assistants and two apprentices living with them, as well as a domestic servant. They may also have used ‘out workers’, women who worked in their own homes for a piece rate.

Life changed again in 1893, when Maldon House was put up for sale. Rather than relocate their business, the two sisters both retired and moved together to Bristol. They didn’t move out immediately, but by 1901 they were renting two rooms in a house in Ashley Down, Bristol. The 1911 census shows that by this time they were living together in their own house in Ashley Down, although one of them was sufficiently unwell to require a live in nurse. Jane died in June 1915, and George arranged for her body to be brought back to Bridgwater and buried in his family plot in the Wembdon Road Cemetery. After this, Fanny returned to Bridgwater and lived with her brother George and niece Amy in 43 Church Street. George died in June 1918, and Fanny died only a few months later in November 1918. She was buried together with her sister, brother and sister in law in the family plot in Wembdon Road Cemetery, Anglican Section H22.

Clare Spicer, Hilary Southall and Jill Trethewey, 12/01/2021