William Hickman, 1842-1923, Anglican Section H, Memorial 21/511, Chemist, Druggist and Dentist

Clare Spicer, Hilary Southall, Jill Trethewey 25/01/2021

William Hickman’s family did not come from Bridgwater, or even Somerset. He was born in 1842 in Newbury, Berkshire, the son of Joseph Frederick Hickman and Martha nee Platt. Joseph Hickman had served an apprenticeship as a chemist and he took over a chemist’s shop in the Market Place in Newbury. Joseph worked hard and built this up to a successful business, and so was able to give his children a good start in life. The family lived over the shop in the Market Place.

William was one of six siblings, with two older sisters Elizabeth and Louisa, a younger sister Emma and two younger brothers, Frederick and Richard. Unfortunately William’s mother Martha died in 1847, when William was only five years old, and Joseph had to manage his work and six children. By 1851, Joseph’s unmarried sister Ann had come to live with him, and Joseph’s household also included an assistant chemist and an apprentice, as well as two house servants, but William was not with his father. In 1851, William, aged 8, and his older sister Louisa, aged 9, were pupils at a small boarding school in Hungerford.

William probably helped his father during school holidays, but by 1861 an 18 year old William was working as an apprentice in a large chemist’s shop in the High Street, Maidstone, Kent. William’s employer was Thomas Stonham, a wholesale and retail chemist, with an establishment of 19 people, including three assistant chemists, and four apprentice chemists. There were also four domestic servants, including a cook, so hopefully William was well fed, as well as getting a thorough training.

As an apprentice chemist, William would have spent a lot of time working in the shop, dealing with customers, selling patent medicines and passing doctor’s prescriptions to the druggist, who would make the prescription up by mixing the basic ingredients. A chemist’s shop in the 19th century usually had a long wooden counter which was highly polished, and behind that row upon row of shelves displaying glass bottles and jars, containing all the ingredients needed for medicines. Some of these bottles would be coloured to indicate the contents, blue might indicate a syrup, while green was often used for a poison. The shop would be filled with the scent of the medicinal ingredients, many of them herbal, such as mint, lavender, coriander, chamomile and sage, while liquids such as vinegar and treacle could be added to make the medicine more palatable. There may also have been small additions of more disturbing substances such as arsenic, mercury and lead. Everything was labelled with great care.

William would also have learnt to be a ‘druggist’ by helping in the dispensary. This would have been a small back room with a work bench containing tools such as a tincture press, for pressing herbs to obtain a liquid, measuring scales, a pestle and mortar for reducing solids to a powder, and a machine for making tablets. Measurements had to be in very small quantities, solids were measured in grains (65mg), scruples (20 grains) and drams (3 scruples, with eight drams in an ounce). Prescriptions were written in Latin, so William would have rapidly acquired a working knowledge of the necessary medical terminology. The druggist would keep a recipe book, listing the composition of medicines for common problems such as indigestion, and coughs, many of them of his own devising.

Chemists began to organise as professional societies in the mid-19th century, and in 1868, the Pharmacy Act of 1868 stipulated that dangerous substances such as arsenic and laudanum could only be sold by registered chemists. It is seems likely that William was able to register as a chemist before 1868 because he had been working as a chemist and druggist for some time already. After 1868 he would have had to take examinations to become a pharmacist.

On the 9th of February 1870, William married Eliza Adey in St Mary’s Church, Paddington, and his uncle Richard, who lived in London, was a witness. Eliza Adey also came from Newbury, so William probably knew her from childhood. Eliza was the daughter of George Adey, a prosperous builder in Newbury, although by 1870 he was retired and described himself as a gentleman. Her mother was Martha, nee Low.

William and Eliza were already expecting their first child, and moved to Bridgwater soon after the wedding. Their son Frederick was born in May 1870 and baptised in St John’s Church Bridgwater on the 29th of May 1870. Eliza’s father George died in November that same year, and although Eliza was one of five children, she probably inherited some money from her father. It appeared later that Eliza was able to buy some property with her own money.

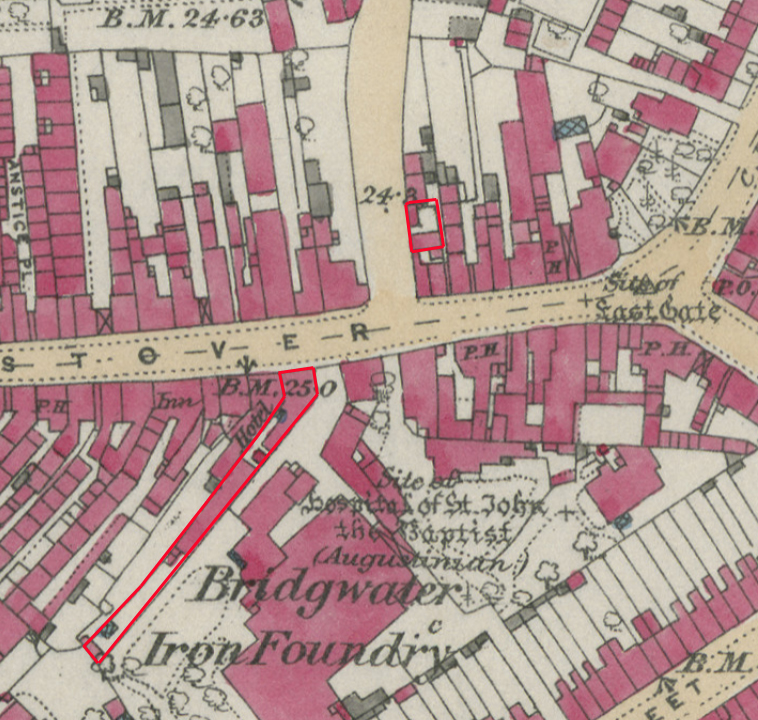

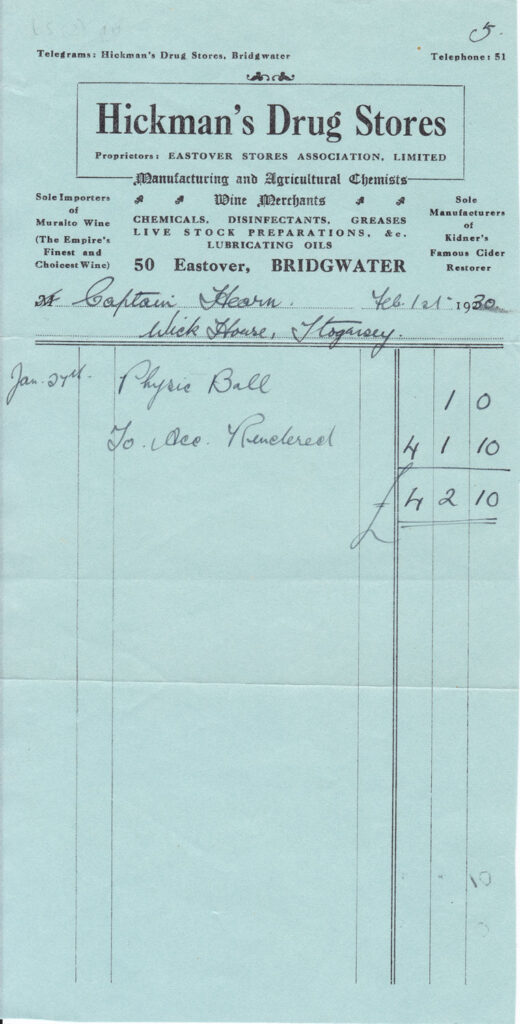

Neither William nor Eliza seemed to have any family connections with Bridgwater, so it is possible that William simply answered an advertisement to buy a chemist’s shop and business there. By April 1871, William and Eliza were living over their own chemist’s shop in Eastover, with their 11 month old baby Frederick. William described himself as a pharmaceutical chemist employing two apprentices, although these two apprentices were not living in with William.

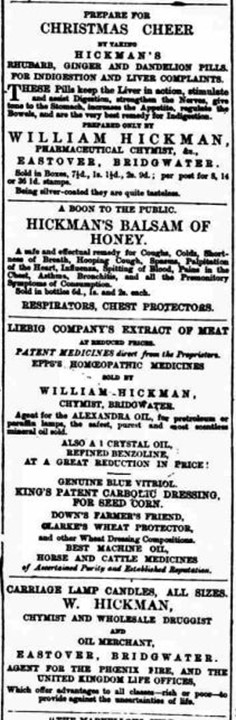

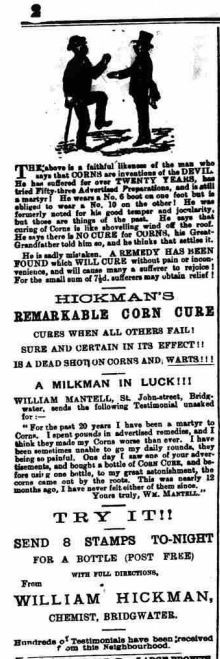

The Bridgwater Mercury in the 1870s carried frequent advertisements, showing William working hard to attract customers, and these advertisements give an idea of the large range of goods he was selling. William was selling a mix of his own remedies and patent medicines, as well as practical health aids, such as chest protectors and toothbrushes. Many people could not afford to go to a doctor, so a chemist provided a vital service by selling cheap ready-made medicines.

William also sold candles and was an agent for lamp oils, as well as preparations suitable for use in agriculture, such as the alarmingly named ‘Blue Vitriol’, and he gained additional income by working as an emigration agent.

Some of his adverts listed many of his goods, items such as:- Remedies for indigestion - Eno’s Fruit Salts, preparations of magnesia, Beckett’s syrup of orange and quinine, treatments for skin and hair such as Clarkes Blood Mixture and skin lotion, Macassar Oil, at least four different hair restorers, tooth pastes such as Floriline for the teeth and gums, Areca nut and cherry toothpastes, hair and tooth brushes, as well as a wide selection of cordials, juices, lemonade and mineral water. His shop would have been busy and well stocked.

As well as products for human use, William sold ‘horse and cattle medicines of every description’.

The products advertised were the ‘over the counter’ remedies, but William would also have stocked products such as laudanum, leeches, still in common medicinal use, and other restricted products such as arsenic, widely used as a rat poison. Customers would have had to sign William’s poisons register to buy this, and William would only have sold to customers he knew.

William’s own remedies advertised – the Rhubarb, Ginger and Dandelion pills for indigestion and liver complaints and the Balsam of Honey for coughs and colds, both sound like pleasant herbal remedies. As a chemist and druggist, William was trained to make up and dispense all sorts of medicines, both those prescribed by a doctor, and those which his own experience had taught him might be helpful. Medical science had not advanced enough to help many serious illnesses, but pain could be eased somewhat with various preparations such as laudanum, an opioid in common use until aspirin was developed in 1899.

Laudanum was useful for pain relief and for diarrhoea, but in Victorian times it was over used, even appearing in mixtures marketed to soothe infants. Laudanum could only be sold by registered chemists after 1868, but it could still be sold over the counter, without prescription, and was part of many patent medicines. It was the cause of accidental deaths and suicides, but the introduction of aspirin as a cheap and safe painkiller meant that in the 20th century there was much less reliance on laudanum.

William advertised the fact that he was an agent for lamp oil, which he stored on his premises, and which proved to be something of a fire hazard. On the 22nd November 1876, the Bridgwater Mercury reported a fire which had erupted at 7 o’clock in the evening at Hickman’s chemists shop. The shop was still open, but William had stepped out for a while. A lad employed by him was carrying a hamper through the store room at the back of the premises, and accidentally knocked the tap on a cistern containing benzoline. As the benzoline began to flow out over the floor and into the yard outside, the lad called for help. William’s two assistants ran in, one had a covered lantern which he placed about 6 yards away from the cistern. Unfortunately the vapour was still able to ignite, also setting fire to a nearby sack of linseed. The immediate explosion of flame rose to a height of about 45 feet, judged by the smoke discolouration on a nearby wall. The two assistants bravely used dampened clothes to put the flames out, so the only result was a relatively small loss of stock. Their courage and prompt action certainly prevented a much more serious fire. It was ironic that at the same time, William was an agent for the Phoenix Fire Insurance company, it is to be hoped that he had insured himself as well.

Both William and Eliza were engaging in the religious, social and charitable life of the town. A month after the fire, they were reported in the Mercury as taking part in a soiree given in aid of the St John’s Church Improvement Fund. Mrs Hickman contributed food to the tea, and William lent a ‘galvanic battery’. The evening included singing and musical entertainments. William was also active on the St John’s Church Burial Board. The following year, on the 20th June 1877, the Mercury gave a report on a funeral, which included William’s name as a councillor of Bridgwater. Chemists were generally well regarded as important members of society.

In 1878, William also registered as a dentist. Up to this time, dentistry was unregulated, but the Dentists Act of 1878 set up a register of dentists, and required all dentists to pass examinations after this time. People who had been practising as dentists for some time up to 1878 were allowed to register as dentists in this year, and William Hickman went on to the Dentists Register from this year onwards.

Before 1878 it was common for chemists to work additionally as dentists, poorer people also visited barbers and even blacksmiths for tooth pulling. It seems extraordinary now that people should consider going to a blacksmith for dentistry, but a blacksmith could make himself a suitable pair of pliers, and would certainly have the strength in his arms to pull a tooth quickly, which was a consideration if you wanted to reduce your pain. Much dentistry at this time consisted simply of pulling out teeth that were causing trouble. Unfortunately many people suffered afterwards with infections.

Again, chemists such as William Hickman were providing a very useful service to the many people who could not afford the fees of a qualified dentist. He also sold tooth brushes and toothpastes, to help with dental hygiene.

The 1870s also saw a significant enlargement of William and Eliza’s family, with the birth of two more sons, Ernest William in 1874, and George Cecil (known as Cecil) in 1876. Their last child, a daughter, Edith Mabel, was born in 1878.

Perhaps the increase in size of their family prompted William and Eliza to move away from their accommodation over the shop in Eastover to a house very nearby at 2 Church Street. In 1881 they were living here with their three younger children and a general servant called Mary Bartlett, a 30 year old unmarried woman from Westonzoyland. William and Eliza must have been good employers as Mary Bartlett remained with them until at least 1911. She spent longer living with William and Eliza than their own children did and really become part of the family. Their eldest child, Frederick, was boarding at the College House School in North Street, Bridgwater.

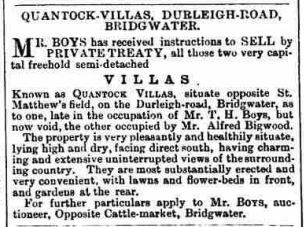

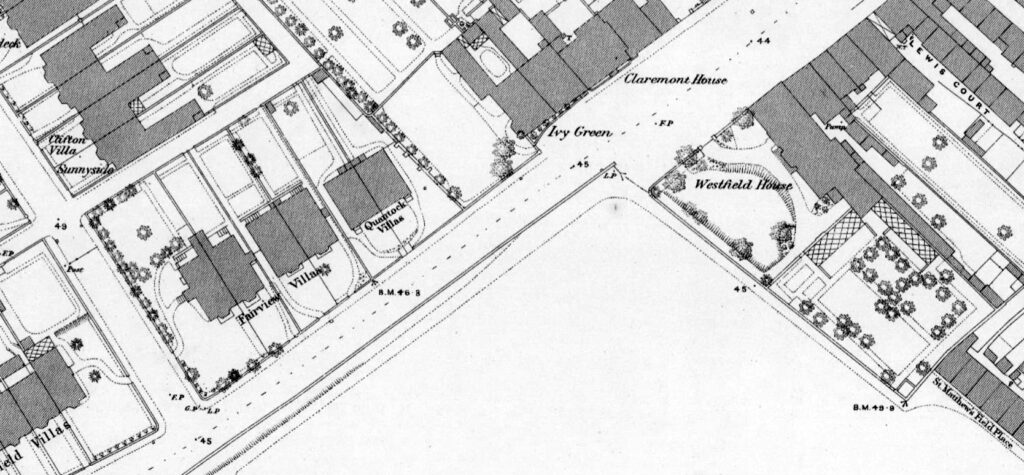

Both William and Eliza had fathers who were good businessmen, and this may have encouraged William to start investing and possibly speculating on the stock market. William certainly started to invest in rental properties, to increase his income. On the 28th of July 1881 in the West Somerset Free Press, a pair of semi-detached houses called Quantock Villas were advertised for sale together. It is likely that this is when William bought these two properties, as his financial situation subsequently grew more difficult in 1882.

Before October 1882, William had been making some investments in stocks and shares, and had unfortunately made a loss. William had made some transactions with the firm Strawbridge and Jones and now owed them £250. When they pressed for payment, William offered them £66, and asked them to wait for the rest, saying that his wife had some good property, which presumably he would have to sell to release funds. Strawbridge and Jones refused to wait for William to sell property to pay the debt, and took immediate proceedings to declare William bankrupt.

What happened next was legally complicated, but following the advice of his solicitor, William’s father Joseph Hickman stepped in to rescue his son by taking over all his son’s assets. Strawbridge and Jones considered this action fraudulent and initiated further legal proceedings. By this time, William’s father Joseph was a very prominent man in Newbury, a former mayor, magistrate and staunch churchman, and such an action would potentially have been very embarrassing for Joseph as well as damaging for William, even though Joseph had followed legal advice. Strawbridge and Jones pursued the case from the Bridgwater County Court to the Chief Judge in a bankruptcy court and finally to the Appeal Court, where at last William and Joseph won their case, although they had to pay their own legal costs. The appeal was reported in the West Somerset Free Press in 1883, and the annulment in the Western Times 1884. William was fortunate to have his father to back him in this expensive action, and no doubt some settlement was reached with William’s creditors. William’s declaration of bankruptcy was annulled, he retained his good name and his chemist’s business continued under the name Hickman and Son.

In 1886, William and Eliza’s eight year old daughter Edith died.

During the 1880s, Mrs Lovibond had been a tenant of William’s for some years, living at 1 Quantock Villas. In 1888, William had sent a letter to Mrs Lovibond asking if he might carry out some building work to improve this house, but Mrs Lovibond was a widow and not in a good state of health, and claimed to have been bewildered by this letter. The builders moved in shortly afterwards and demolished part of the front wall, excavated a room under the house and put a window in for the new room, all while Mrs Lovibond was still living there. This caused considerable mess and some damp damage, so Mrs Lovibond withheld payment of her rent of £4 15s, claiming that ‘cascades of water’ had damaged her furniture. She also made a claim of £10 for compensation, saying that two pianos and many watercolour paintings had been ruined. The subsequent court case was reported in the Weston Super Mare Gazette on the 22nd of June 1889. The case was about their dispute over exactly what had happened, who was responsible and who should pay. After several counter accusations, William and Mrs Lovibond settled on the net amount of £1 15s to be paid by her for rent, after a deduction of £3 for compensation. By this time, Mrs Lovibond had already left Bridgwater for Burnham.

During 1889, William advertised both number 1 and number 2 Quantock Villas as available for rent.

By 1891, William and Eliza had moved out of 2 Church Street and were back living over his chemist’s shop at 50, Eastover, which was next to the White Hart Inn. They might have sold a property in order to re pay William’s father for any money he may have lent them in 1883. By returning to live over the shop, William was managing carefully within his means. Living with William and Eliza were two of their sons. Their eldest son Frederick Herbert, also working as a chemist now, their youngest son George Cecil was at home and working as a journalist, and a 23 year old chemist’s assistant from Bolton was boarding there as well. Of course, Mary Bartlett was there too. Their middle son, Ernest, was living and working in Dorchester, as a draper’s assistant.

In 1892, William became a member of the Freemason’s, joining the Lodge of Perpetual Friendship in Bridgwater.

On the 5th of January 1894, William’s father Joseph died at his home in Newbury. Joseph was a very prominent man in Newbury, and the long obituary printed in the Newbury Weekly News on 11th January 1894 describes Joseph as ‘Alderman Hickman, the Father of the Corporation’. William was reported as having attended the funeral, where he would have been reunited with his brothers, Frederick, who had taken over their father’s chemist’s shop, and Richard, now a general practitioner in Newbury.

The next two years saw William and Eliza’s two eldest boys get married. Ernest married Ellen Marriott in the second quarter of 1898, in Fareham in Hampshire. On the 27th of December 1899, Frederick married Ethel Darch in Woolavington, Somerset. Frederick and Ethel’s marriage was witnessed by both their fathers and by Fred’s youngest brother (George) Cecil.

In 1901, William and Eliza had moved away from living over the shop to their house at 2 Quantock Villas on the Durleigh Road, although William was still working as a chemist in their shop. All their children had now left home, but the faithful Mary Bartlett was still with them.

Frederick and Ethel were now living over his father’s chemist’s shop at 50, Eastover, Bridgwater in 1901, but Frederick was no longer working with his father. Although Frederick had trained as a chemist, he now described himself as an oil merchant, working at home on his own account. As William had been an agent for various lamp oil products for many years, it is likely that Frederick was now also working on this side of the business. Living with them was a ‘monthly nurse’, because Ethel was due to have her first baby any day. Frederick and Ethel’s son Charles William was born in Bridgwater on the 6th of April 1901, and no doubt William and Eliza were delighted with their first grandchild. Ethel returned to her family home in Woolavington to have Charles christened. They had another son, John Herbert, in 1909.

Ernest and his wife Ellen had moved to Bristol after their marriage, and Ernest was working as a hosiery haberdasher. Ernest and Ellen had a daughter, Doris in 1902. Also living with Ernest was his younger brother Cecil, still working as a reporter.

By 1911, William had retired, and was still living at 2 Quantock Villas, and Mary Bartlett was still with him. Eliza had gone on a visit to their son Ernest in Bristol, where Ernest now had his own gent’s outfitter business. Perhaps Ernest’s house was small, as Ernest’s eight year old daughter Doris was staying with a friend nearby.

William’s wife Eliza died on the 4th of July 1919, and she was buried in the Wembdon Road Cemetery in the Anglican section, plot H21. Her address was given as 2 Durleigh Road, which was the same address for Quantock Villas, so they were still living in the same house.

William died at the end of September 1923, and he was buried with Eliza on the 4th of October 1923 in plot H21.

William lived through a time of great change in the history of pharmaceutical and dental practice. He began by following the traditional route of his father and learning his trade as an apprentice, but when regulations changed in the late 1860s, he was able to qualify to be registered and continue to practice by reason of his years of experience. He was a man who took an active part in charitable works for the church, and on the town council, and devised remedies and gave advice to ease suffering and improve the health of many poorer people.

The memorial was repaired in 2020. Read about it here.

References

Ancestry.com

Bridgwater Mercury

West Somerset Free Press

Western Times

Western super Mare Gazette

Chemistanddruggist.co.uk

Bda.org