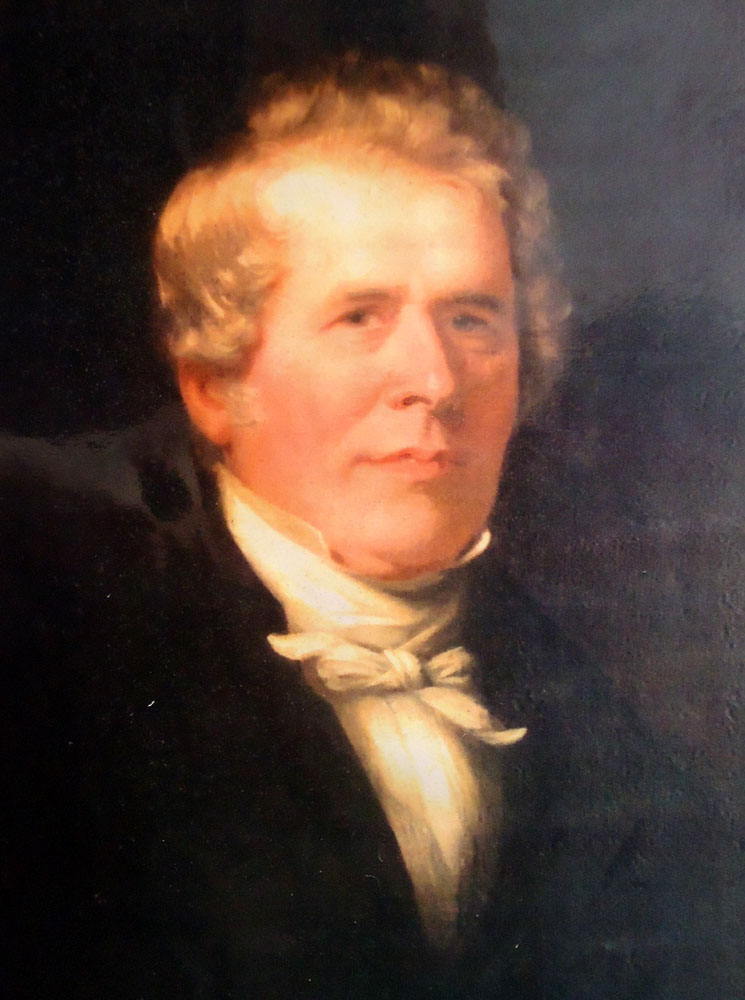

CAPTAIN GEORGE LEWIS BROWNE R.N. (1784-1856) Trafalgar veteran, Barrister, Bank Manager and Magistrate

- Mrs Ann Browne, nee Pyke (1781-1846), his wife

- Sophia Maria Browne (1783-1853), his sister

- Fanny Browne (1794-1871), his sister

by Jillian Trethewey, Hilary Southall and Clare Spicer 18/7/2023.

Thank you to all who helped with your expert knowledge and advice, particularly with regards to George Browne’s naval career. Thank you also to all who gave permission for use of illustrations.

The Battle of Trafalgar in 1805 was a celebrated victory of the Royal Navy during the Napoleonic Wars. A Bridgwater man, then Signals Lt. George Browne, fought bravely with Admiral Nelson in HMS Victory that day. Captain George Browne lived and worked in Bridgwater again for the last twenty years of his life. George’s brothers William Browne and John Browne also have biographies on this website.

Early Years

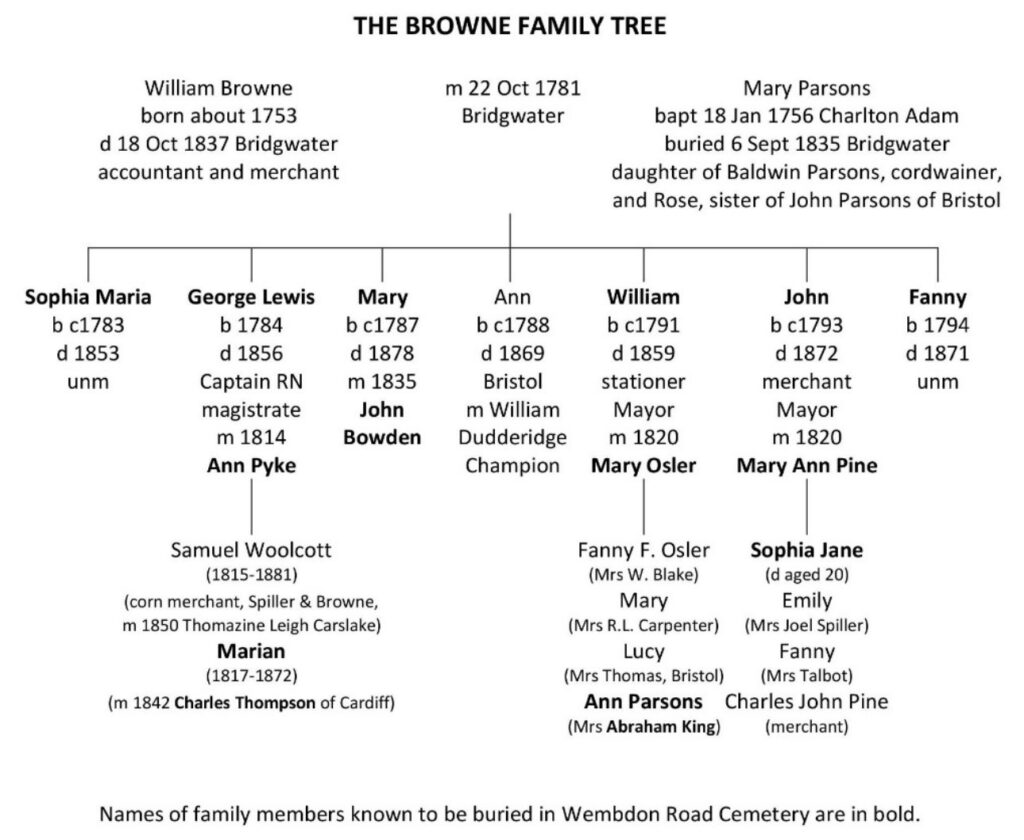

William Browne (c1753-1837) was an accountant and merchant of The Lions, Quay, Bridgwater. [1] He was a member of the Christ Church Unitarian congregation in Dampiet Street. His Unitarian friends were important to him both socially and in business. William married Mary Parsons in 1781 and they had seven children (see Appendix A). George was born at Bridgwater on 15 January 1784.[2] He was their second child and eldest son and the only member of the family known to have gone to sea. First his elder sister Sophia Maria Browne (born 1783) and then George, were baptised by a visiting Unitarian minister at Dulverton, Somerset, suggesting but not proving a connection with the Browne family of Dulverton. It wasn’t easy to arrange. Dulverton via Taunton is about forty miles by road from Bridgwater and the minister had to come from Hatherleigh in Devon. George was two and a half when he was baptised George Lewis Browne on 30 July 1786. Lewis was possibly after a Unitarian minister in Wales. In adult life George rarely used his middle name.

George grew up in Bridgwater and attended the local grammar school from the age of seven, but he was already learning about ships. In the middle of the town, the river Parrett was busy with sailing ships loading and unloading. Goods were brought up and down the river on barges, or to and from the quays by horse and cart. Any boy would have been fascinated by all the activity and the sailors’ stories. George later told his family how he used to climb the masts of ships moored in the Parrett.[3]

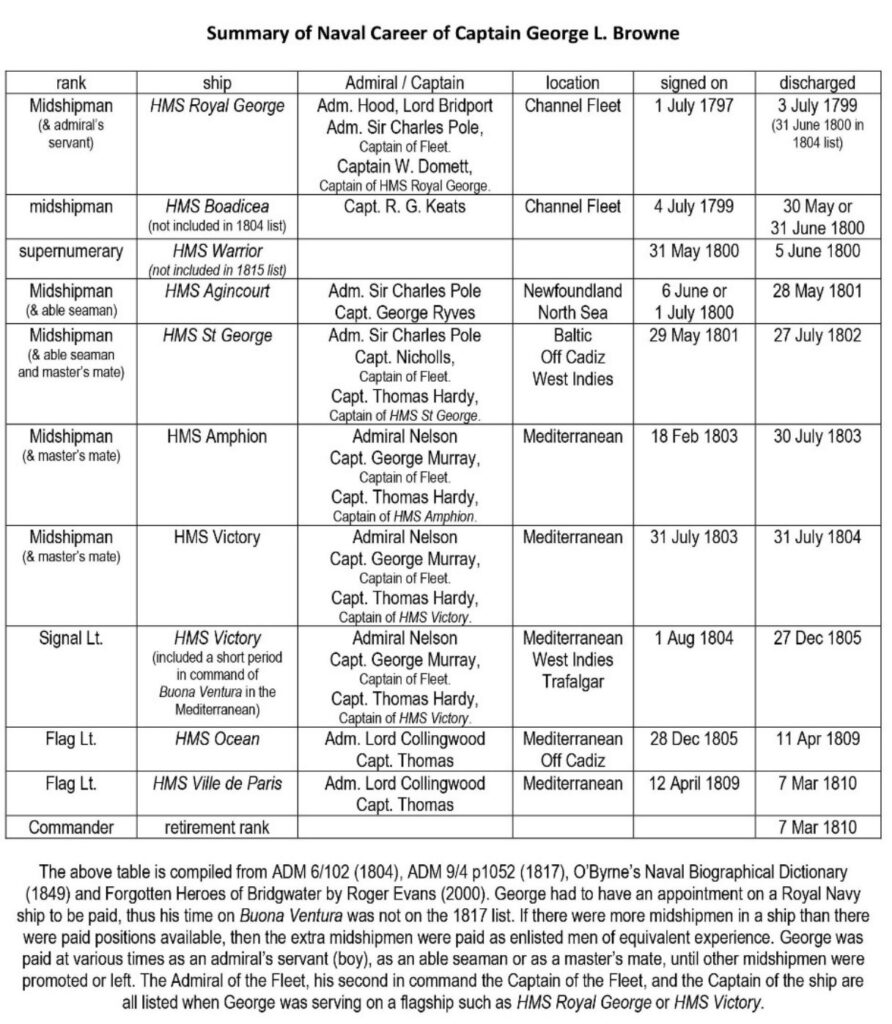

George joined the Royal Navy on 1 July 1797, at Torbay. His father took him to Admiral Sir Charles Pole, second in command of the Channel Fleet under Admiral Hood, on board the flagship HMS Royal George, a 100-gun ship of the line. [4] Britain was at war and the Royal Navy needed men and boys, but even so, this was a prestigious start for George. The captain of a Royal Navy ship, or in this case an admiral, chose his own servants (boys) to be trained as midshipmen. There is no written record of how William Browne obtained the admiral’s patronage for his son, but there is a possible connection. John Langston was MP for Bridgwater from 1790 to 1796 and his relative by marriage and running mate in 1796 was Sir Charles Pole (1757-1830).[5] Presumably William somehow used his connections to obtain an introduction.

Midshipman Browne

Boys from the age of twelve were trained as midshipmen on board ship.[6] There were a limited number of positions for midshipmen on each ship and George was officially an admiral’s servant (Boy First Class) for his first nine months. They were soon exposed to the strict discipline of the Royal Navy and the sights and sounds of battle. Britain was fighting Napoleon and the ships of the Channel Fleet were blockading French ports. The Royal George was present when HMS Mars fired on and captured the French Hercule on 21 April 1798. The Mars lost 31 men killed and 60 injured. The French ship lost 290 men killed and injured. This was only ten days after George was made a midshipman. One of the other young midshipmen serving on the Royal George at the same time was a boy from Sidmouth, Devon, named John Carslake (born 1785). Although they did not always serve in the same ships, they were to remain lifelong friends.[7]

George served in the Royal George for two years, followed by another year with the Channel Fleet in HMS Boadicea. Blockading involved long periods of just watching and waiting, with brief periods of action when an enemy ship attempted to slip in or out of port. There were regular chores to keep the ships seaworthy and regular gun drill so that the ship’s companies were battle ready, but it could be monotonous. George was transferred to HMS Boadicea, Captain R. G. Keats, during the blockade of the French Fleet at Brest. Boadicea was a 38-gun frigate and Captain Keats and his crew captured many prizes when cruising the Channel in between periods on blockade.[8]

In mid-1800, the Commander of the Channel Fleet retired and, underlining the importance of patronage in these appointments, when Admiral Sir Charles Pole was reassigned, he took George with him. The Admiral was now Governor and Commander-in-Chief of Newfoundland, with his flag aboard HMS Agincourt, 64 guns, Captain George Ryves. The Royal Navy was responsible for protecting Newfoundland’s fishing fleet and maritime trade. St John’s was the last port before the north Atlantic crossing and the safety of Falmouth. Initially George had to accept a position as an able seaman, but after a month he was on the payroll as a midshipman.

Six months later Sir Charles Pole was promoted to Vice-Admiral and became Commander-in-Chief in the Baltic. He raised his flag aboard HMS St George, 98 guns, Captain Thomas M. Hardy, and took George with him, though as an able seaman again for the first month. The British relied on Scandinavian supplies such as timber for masts and spas, tar and pitch. Control of Danish ports was crucial to access to the Baltic, but Denmark, Sweden and Russia were threatening to form a pact and side with the French. This resulted in the Battle of Copenhagen on 2 April 1801, which the British won.[9] While diplomatic negotiations continued, the St George surveyed the channels between the Danish islands that gave access to the Baltic Sea. The fleet sailed home in July. The St George then joined the blockade off Cadiz. In December Sir Charles Pole returned to England and did not go to sea again. George had lost his mentor. He sailed on the St George to the West Indies, paid as a master’s mate.

By March 1802, that phase of the war was over. George returned to England on the St George in July 1802 and then was unable to find another ship. It was a chance to go home and forget the hardships and discipline of life at sea.

Captain Thomas M. Hardy of HMS Amphion, a 32-gun frigate, knew George from the St George and in February 1803, George joined the Amphion as a master’s mate, as the ship already had its quota of midshipmen. Britain had remained uneasy about the threat posed by Napoleon and war was declared again in May 1803. Admiral Nelson was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Mediterranean Fleet and sailed from Portsmouth in HMS Victory, 104 guns, Captain Sutton. Victory was delayed off Brest and Nelson transferred his flag temporarily to HMS Amphion, to sail with haste to Malta and his new command. Hardy had been Nelson’s flag captain in Victory in the Baltic. When Victory finally caught up with them, Nelson transferred his flag back to Victory, with Hardy as captain and George as a midshipman. Captain Sutton took command of Amphion. The Mediterranean fleet were primarily blockading the French port of Toulon, preventing the French navy from leaving. The blockade went on for months and then years.

Meanwhile George was completing his training as a midshipman. By March 1804 he had been at sea for six years and two months and on that basis was eligible to sit the lieutenant’s exam. At the examination, each midshipman was interviewed by a panel of three senior captains and were questioned on seamanship and theory of navigation. The Navy Board did not set specific questions and so the examination could vary greatly in difficulty, with some candidates having to give detailed answers to demonstrate their knowledge and others being given an easier ride. The examination was pretty intimidating although occasionally a candidate found he was being examined by a relative. George was examined on 21 March 1804, on board HMS Victory, by Captain Richard Goodwin Keats, Captain Robert Barlow and one other whose signature is illegible. [10]

“In pursuance of the Directions of Lord Viscount Nelson KB Vice Admiral of the Blue, Commander in Chief of His Majesty’s Ships and Vessels, employed and to be employed on the Mediterranean Station, dated the 21st day of March 1804, we have examined Mr George Browne of His Majesty’s Ship Victory, who appears to be more than twenty-one years and has been to sea more than six years in the Ships and Qualities undermentioned, viz.”

This was followed by a list of ships on which George had served, with dates, plus the names of the captains (see Appendix B). The statement of the panel then continued:

“He produceth Journals kept by himself for the Saint George, Royal George, Agincourt, Amphion and Victory, and Certificates from Captains Domett, Ryves, Nicholls, Thompson, Lobb and Hardy of his Diligence, Sobriety, Obedience to command.

He can splice, knot, reef a sail, work a ship in sailing, shift his tides, keep a reckoning of a ship’s way by plane sailing and Mercator, observe by the sun or star, find the variation of the compass and is qualified to do his duty as an able seaman and midshipman.

Given under our hands On Board His Majesty’s Ship Victory at Sea this 21st day of March 1804

R ………., R.G. Keats, Rob Barlow”

George was only twenty in 1804, but on the documentation for his Lieutenant’s Passing Certificate provided to the Navy Board in 1804, he was said to have been fifteen when he joined the service, thus two years older. Somehow this was overlooked. In any case, George was very young to be a successful candidate and this is another indication that he was an exceptional officer. [11] He was now qualified to be a lieutenant in the Royal Navy, but that did not mean an automatic promotion or a commission to a ship at that rank. Nelson wrote:

“I assure you that I most sincerely wish to promote Browne, who is an ornament to our service, but alas! Nobody will be so good as to die, nor will the French kill us. What can I do? – but I live in hopes.” [12]

The Battle of Trafalgar

Nelson presented George with his Lieutenant’s commission on the quarter deck of the Victory on 1 August 1804. It was a reward for two and a half years’ dedicated service. During this time George scarcely went ashore except when on duty and spent much of his leisure hours studying for promotion or training the boys for whom he was responsible.[13]

Every lieutenant at sea was required to keep a log in which every day he recorded wind speed etc., latitude and longitude and the nearest land, plus brief remarks about the weather and the work done that day. Most entries were only two, three or four lines. For instance, returning from the West Indies on Friday 2 August 1805:

“am cloudy and variable weather at 7.30 tacked to the westward made and shortened sail occasionally – squadron in company – ditto weather.”

On Sundays divine service was listed. The entries were very brief and matter of fact. The only time individual seamen were named was when they had been punished. It was not uncommon for men to be given three dozen lashes for drunkenness or neglect of duty. [14]

The blockade of Toulon had dragged on. There was even time for some fun. George didn’t drink alcohol and particularly liked Bristol Water. On one occasion it was Nelson who tried to trick him with a substitute, but George was not fooled and politely said the steward was mistaken in his labelling. Nelson gave George the temporary command of Buona Ventura, a Spanish prize, and a Royal Navy crew, with orders to cruise the Barcelona coast. This was very good experience for a young officer and George captured an enemy merchant ship and its valuable cargo. [15]

In April 1805, the French fleet commanded by Admiral Villeneuve eluded the British blockade and escaped Toulon. This was Villeneuve’s second attempt and this time the French fleet sailed through the Strait of Gibraltar, bound for the West Indies. Nelson was determined to follow and fight but spent all June searching the Caribbean without success. Back in London, to Nelson’s surprise, he and his fleet were praised for protecting the British West Indies from a French invasion. Nelson was now a celebrity and was cheered by people in the street.

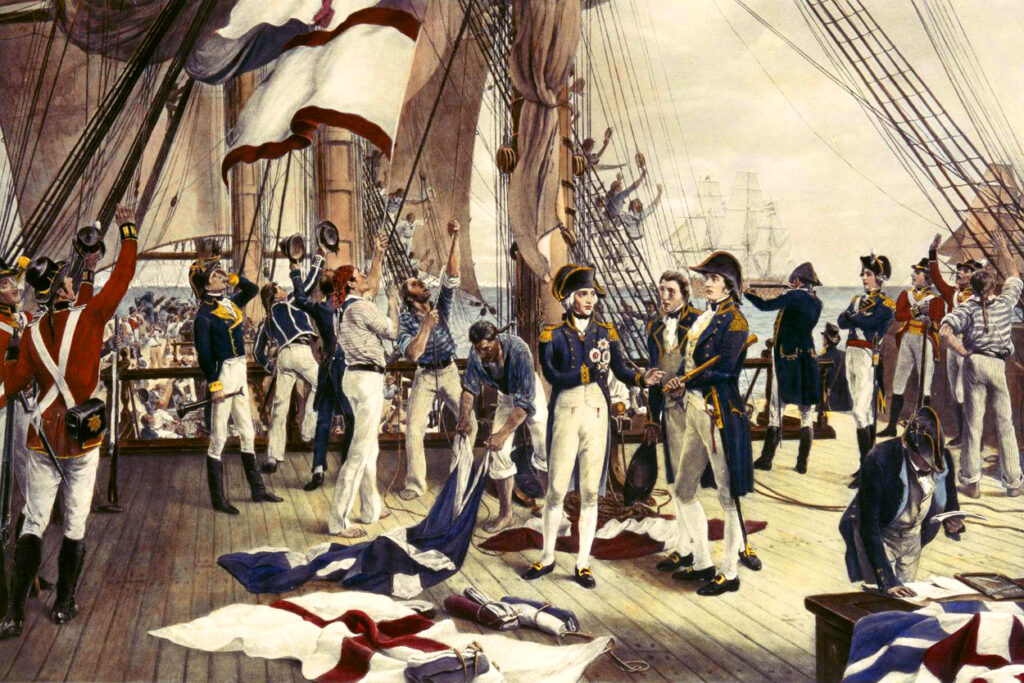

In early September, news reached Nelson in London that the combined French and Spanish fleets were at anchor off Cadiz. By the end of September, Victory, with Signals Lt. George Browne on board, had joined the British fleet off Cadiz and Nelson took command. Villeneuve had thirty-three ships of the line and Nelson only twenty-seven. Nelson devised a strategy to defeat the larger force and spent the next three weeks ensuring his captains understood and that his ships were ready. He had a very special relationship with his Captains whom he referred to as his Band of Brothers.

On Sunday October 20th, British frigates sighted the enemy fleet leaving Cadiz harbour and sailing west. Early on the morning of the Monday October 21st, Nelson ordered the Victory to sail towards the enemy and signalled the fleet to battle stations. The Battle of Trafalgar was about to begin.

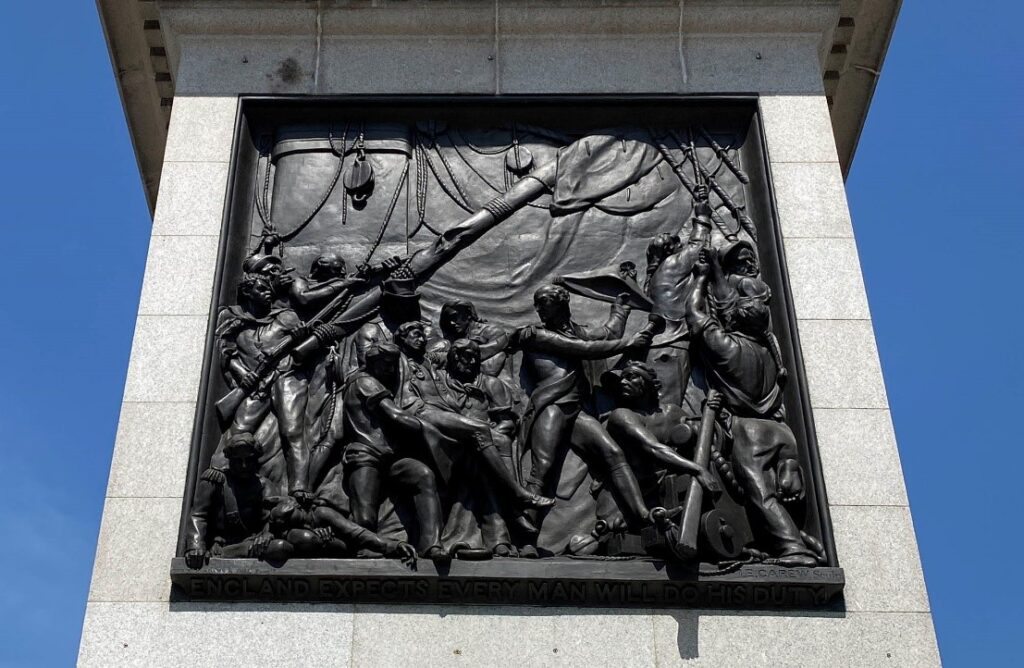

Just before the battle, Nelson ordered this famous message to be signalled to his ships with haste: “England expects every man to do his duty.” At George’s funeral many years later, a good friend related George’s version of events. “Young Browne was the signal lieutenant, and he received the Admiral's orders in the cabin, the dispatch being directed to run ‘Lord Nelson expects’ etc… Browne suggested the substitution of the word ‘England,’ which Nelson instantly adopted, thanking him for the improvement. Browne did not hoist the signal himself, but directed it be done by another. It passed through several hands and the substitution has been claimed by others.” [16]

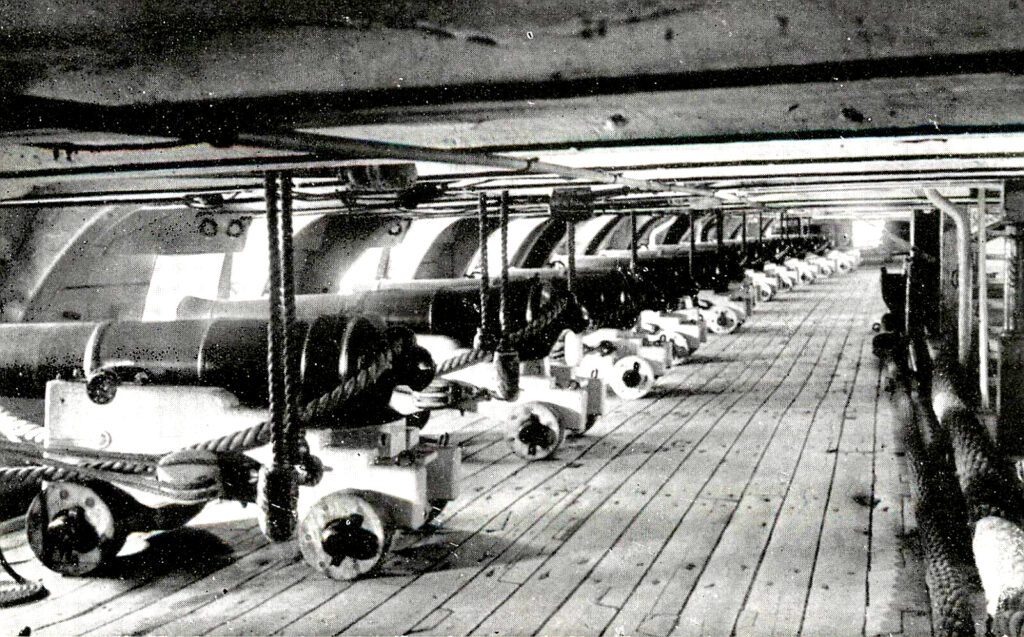

George’s Action Station was as Officer of the Quarters for a section of guns on the middle deck. He was thus responsible for a good number of guns, between a quarter and a third of those on that deck. George’s principal task was to keep the guns firing whenever they had a target. [17]

Here is George’s account of the battle from his handwritten log:

“Monday 21 October 1805, Cape Trafalgar EbS 5 leagues. Fresh breezes and cloudy the lookout ships making the signal for the Enemy’s position and number. Am ditto weather observed the Enemy bearing EbS 10 miles cleared for Action Enemy Line consisting of 33 Sail of the Line 6 Frigates & 2 Brigs in a line of Battle laying too on the Starbd Tack, the British Fleet consisting of 27 Sail of the Line 4 Frigates a Schooner & Cutter all sail set bearing down on the Enemy – Fleet in Co.

Moderate weather at 11.40 the action commenced between the Royal Sovereign and the rear of the Enemy’s Line at 11.50 the Van of the Enemy’s line opened their Fire on us all sail set at 12.15 opened our fire at 12.20 in attempting to break through the Enemy’s line fell on board the 10th and 11th ships the Action became General with the Van ships of both columns, at 1.15 the Right Honble Lord Viscount Nelson was wounded, at 1.30 the Redoubtable having struck ceased firing our Starbd Guns, the Action continued on the Larbd side with the Santisima Trinidada and some other ships at 3.0 all the Enemy’s ships near us having struck ceased firing, observed the Royal Sovereign had lost her Main and Mizen Mast, and several dismasted Prizes around her; at 3.10 4 of the Enemy’s Van Tack’d & stood along our line & engaged us in passing at 3.40 made the signal for our ships to keep their wind, for the purpose of attacking the Enemy’s Van at 4.45 the Spanish Rear Adml struck and one of the Enemy’s ships blew up, the Right Honble Lord Viscount Nelson Departed this life, at 5 the Mizen Mast fell, our ships employed in taking possession of the Prizes, Vice Adml Collingwood hoisted his Flag on board the Euryalus, employed securing the Masts and Bowsprit sounded occasionally from 19 to 13 fms observed 14 sail of the Enemy standing to the Northward and 3 to the Southward. …”

There is no doubt that George was one of many very brave men serving in Victory that day. They remained at their stations despite the enemy’s close-range fire causing significant damage, death and injuries. As the cannon balls hit the thick wooden planking huge splinters, up to a metre long were sent flying across crowded gun decks causing horrendous injuries.

Nelson’s unorthodox and highly irregular tactic was to break through the enemy’s single line of thirty-three ships in two places. Victory, leading the left column, was under fire for forty minutes while her own guns remained silent. The guns faced port and starboard, but not straight ahead. All George and his men could do was move any dead or wounded men below deck and keep the guns clear of wreckage. [18] As Victory sailed between two French ships, she opened fire on both sides and caused immense damage to the enemy ships.

But the battle did not all go Victory’s way. At one point Victory’s starboard guns were so close to the French ship Redoubtable, that the guns were nearly touching Redoubtable's side, and the French had been preparing to board. Gunners were called on deck to repel boarders. HMS Temeraire approached and fired on the Redoubtable just in time. To avoid shot from Victory’s guns passing through the French flagship into the Temeraire on the other side, the guns were depressed with a lower charge of powder.[19]

At about 1.30 pm a sharpshooter high in one of Redoubtable’s masts caught sight of the blue and gold of Nelson’s dress uniform. He took aim and fired the musket ball which hit the Admiral in the shoulder and lodged near his spine. He was carried below accompanied by Captain Hardy. Nelson is famous for saying, as he lay dying, “Kiss me Hardy.” He lived long enough to hear from Hardy that they had won the battle. His final words were “Thank God I have done my duty” and “God and my country.”

After the battle, Victory sailed to Gibraltar for repairs and to take the wounded to the naval hospital there. Urgent repairs were made and Victory returned to England.

George Browne reflected on the battle and Nelson's leadership in a letter to his parents:

"...The frequent communications he had with his Admirals and captains put them in possession of all his plans, so that his mode of attack was well known to every officer of the fleet. No doubt this action from the novelty of attack will be more discussed than any other that has ever been fought. Some will not fail to attribute rashness to the conduct of Lord Nelson. But he well considered the importance of a decisive naval victory at this crisis, and has frequently said since we left England that should he be so fortunate as to fall in with the enemy a total defeat should be the result on one side or the other..."

George could not have predicted how Nelson’s memory is still honoured:

"...We have bought the remains of our deceased chief home in a butt of rum. I suppose he will be sent on shore with the honours of war, and there will be an end to all his greatness..." [20]

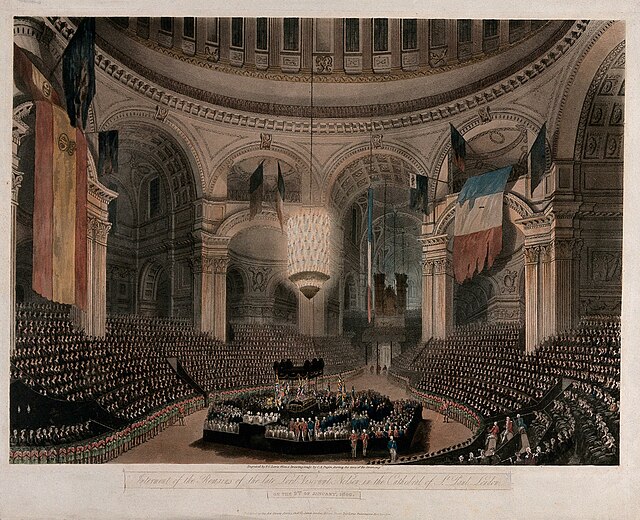

George was one of the men bearing Nelson’s banner rolls at the state funeral. He was present at the graveside as Nelson’s coffin was laid to rest.

Commander Browne

George returned to sea in HMS Ocean and then HMS Ville de Paris, once more serving in the Mediterranean and off Cadiz. The blockades continued, enemy ships were caught slipping in or out of harbour and the British captured prizes, but there were no major battles. Nelson’s successor as Commander of the Channel Fleet was Admiral Lord Collingwood. By early 1810 Collingwood was in poor health and had requested that the Admiralty allow him to return home.

Two weeks before he died, Collingwood wrote to Lord Mulgrave:

“Your Lordship in a former letter, was so good as to say that you would regard those officers whom I mentioned as having served long with me. There are three lieutenants who have served with me in this station more than four years and are men of character: Lieut. Joseph Simmonds was an officer in the Royal Sovereign in the action (Trafalgar); all his life has been service; Lieut. George Browne was an officer in the Victory at the same time and is a well-qualified officer, as is Lieut. Richard Coote. I beg to present these gentlemen to your lordship as officers who services under my command have greatly interested me in their advancement.” [21]

Collingwood died aboard the Ville de Paris on 7 March 1810. George accompanied the admiral's body back to England.

George was finally promoted to Commander, backdated to 7 March 1810, but did not go to sea again. Competition for an appointment as a commander was intense and he had once more lost his mentor. Also, the hardships, danger and strict discipline of life in the Royal Navy were made more bearable by the thought of prize money. It was one of the incentives for going to sea in the first place. For a young man without family wealth, it was potentially a means of affording a home and supporting a wife and family. When fewer ships were captured, there was less prize money to be distributed amongst the officers and crew.

After Trafalgar, George received £65 11s prize money, a £161 share of the government grant and his regular pay in 1806 was £9 2s per month. Together with other prize money received before and after Trafalgar, George suddenly had enough to plan his future. In addition, when he went ashore in 1810 he remained on half pay. [22]

Farmer and Barrister

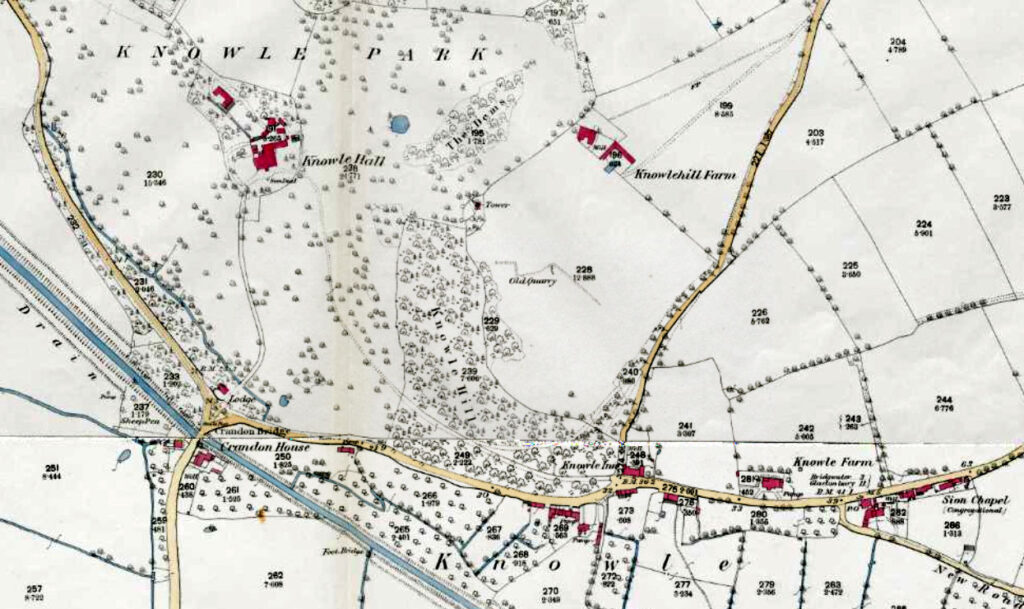

George returned to Bridgwater and leased Knowle Hill Farm at Puriton. He married Ann Pyke of Bridgwater on 18 June 1814. Ann, aged thirty-three, was the daughter of Bridgwater brazier and ironmonger Thomas Pyke and his wife Ann nee Woolcott. George and Ann knew each other from childhood as both families were members of the Unitarian Church in Bridgwater. They had two surviving children, Samuel in 1815 and Marian in 1817, both born at Puriton. [23]

George and Ann were not happy at Knowle Hill. George decided to leave Somerset and become a barrister. Most lawyers in the early 19th century began as clerks working for a solicitor or barrister and only a few went to university. Perhaps George did work for a solicitor in Bridgwater for a time, but then was encouraged to aim higher. To become a barrister, he had to move to London and join one of the four Inns of Court. In the meantime, George rented out his farm, but then suffered a major financial loss when his tenant failed to pay for the stock and other farm assets.

George worked as a conveyancer, a legal clerk who prepared the documents required for land transactions, but he needed a position in the chambers of a ‘bencher’ or senior barrister of one of the Inns. George was “living in great seclusion” and not socialising with prospective employers, probably because he was supporting his wife and children on half-pay. Learning of his plight, a friend took him to the chambers of a young barrister named Matthew Davenport Hill. Matthew’s family were schoolteachers in Birmingham and he had been a struggling law student himself. His subsequent distinguished career suggests that he would have quickly realised that being a Trafalgar veteran, the colloquial term was a ‘Nelson’s man,’ would give George a good chance. Matthew introduced George to an appropriate bencher and George was admitted to the Inner Temple Inn of Court on 23 November 1816. He was then a pupil barrister who studied hard and ‘kept his terms’ meaning that he ate the required number of dinners at the Inn, which proved attendance, and participated in the required exercises or ‘readings in chambers.’ There was no formal exam. Two practising barristers of at least five years’ standing proposed George and he was called to the Bar on 8 February 1822.[24] [25]

George practised as a barrister in Exeter, Devon. He and Ann and the children lived in a Georgian House in Dix’s Field, just east of central Exeter. As well as his legal practice, George was a member of the Dissenters of Exeter and chaired a meeting in 1834 about church rates and the need to petition the House of Commons. As one friend wrote, “Every good and liberal work secured his active co-operation and support.”[26] In about 1835, George retired from his legal practice and left Exeter.

Return to Bridgwater

George and Ann returned to Bridgwater. His elderly parents did not have long to live and George was the eldest son. Also, his brothers’ businesses were growing fast and in 1835 John Browne had been elected to the Bridgwater Borough Council. If George wanted to support his brothers and have some standing in the town, he needed to go home, but he also needed well-paying work.

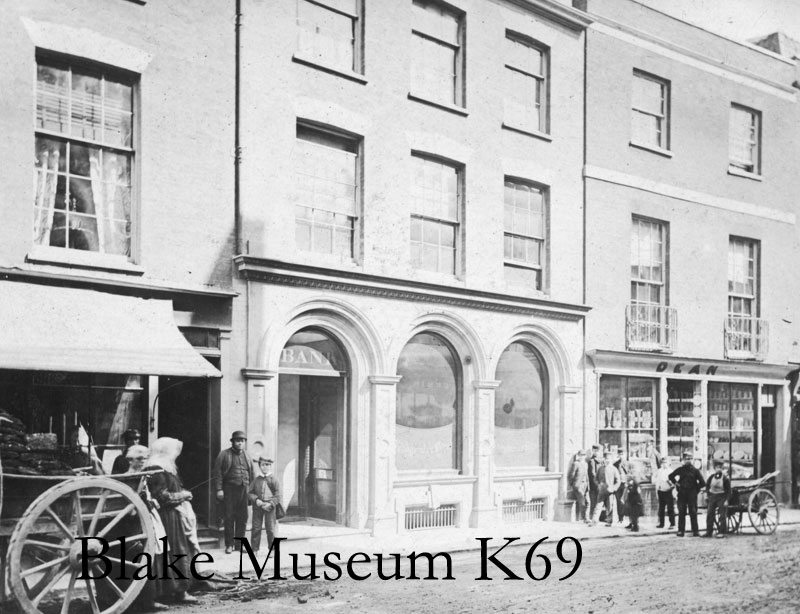

By June 1835 George had been appointed manager of the Bridgwater branch of the West of England and South Wales District Bank. As there was very little regulation of business practices, George had to decide whether the businessmen asking him for loans were a good risk or just scoundrels. He also had to work with the bank’s directors, with their eyes on the profits, and the staff. Sometime in 1837 George was appointed as a magistrate for the County of Somerset and the Borough of Bridgwater. In 1840 George retired from the navy with the rank of post-captain.

George was never elected mayor like his brothers, but he was still a public figure. In August 1839 he chaired a meeting of the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society in Bridgwater, which both of his brothers also attended. During the twenty years that George was a magistrate in Bridgwater, there are many newspaper references to the court cases over which he presided and to the public events and business interests that he shared with his brothers. For instance, they had owned Withy Bow Farm at East Huntspill since at least 1832. George was almost certainly one of the Unitarian businessmen who supported William Browne’s Provident Place development in 1845.

The census of 1841 gives a snapshot of Bridgwater residents on one night. George Browne, 58, a banker, and Ann, 60, were living over the bank in Cornhill with their adult son and daughter, George’s sister Fanny, 48, and two other relatives. A young accountant and three servants were living at the same address. In 1845 Samuel was away from home and George wrote to “my dear Samuel” with family and business news but was relying on his wife Ann to send Samuel more details in her letter. [27] Samuel was a corn merchant in partnership with Joel Spiller in Spiller & Browne.

Mrs Ann Browne died in October 1846 and was buried in the Unitarian churchyard. Soon both children had left home. Samuel married Thomazine Leigh Carslake, the daughter of George’s old friend John Carslake. They moved to London. Marian married local ironmonger Charles Thompson and went with him to Cardiff.

In 1840, George’s friends had joined others in campaigning for Trafalgar veterans to be recognised in the same way as Waterloo veterans. [28] The wheels turned slowly, but in 1847 the Admiralty advertised for sailors who had served in the Royal Naval battles of 1793-1840, to send in written applications for the appropriate award. In 1848 George finally received the Naval General Service Medal with the Trafalgar Clasp. [29]

George’s usual court appearances as magistrate and his work at the bank continued.

A cholera epidemic began in London in 1848 and the disease spread quickly. Local councils redoubled their efforts to clear up “nuisances” such as overflowing drains and cesspits. People were afraid as there was no definitive treatment for cholera and in London many people were dying. In January 1849, it was revealed in the newspapers that 180 pauper children had died of cholera in a children’s workhouse in Lower Tooting, Surrey. There was gross overcrowding, poor sanitation and lack of appropriate care. The master had failed to send the sick children to hospital and was charged with manslaughter.

Then in February 1849, a young woman bravely complained about the poor conditions in the Bridgwater workhouse. This was the beginning of a battle between the Bridgwater magistrates who supported her concerns on one side and the Bridgwater Board of Guardians, who were responsible for the workhouse, on the other. The Board really should have known that George, a Nelson’s man, was not going to back down. He knew cholera was a danger to Bridgwater, he knew what measures needed to be taken and he was not going to be intimidated. The story ran in the Bridgwater Times.[30]

“Ann Young, a woman aged about twenty-seven, declared that she left Plymouth to join her husband in Bristol, that she became ill on the road from excessive fatigue and having expended all her money before she arrived in Taunton, she was there obliged to apply for relief and was accommodated in the Union. On Friday last (9th February) she walked from Taunton to Bridgwater and obtained an order to the Union House from the relieving officer. On her going there, a man that she believed to be the Porter, … showed her to the sleeping room, which she found in a most offensive state. The bed which was allotted to her by the man was dirty so as to be altogether unfit for anyone to sleep upon. This she represented to him and asked for the bed linen and blanket, when she was informed that the Guardians did not allow any. She afterwards told the man that she felt very unwell from the offensive smell and the extreme coldness of the place and that she would leave the House and get a bed in the Town if he would give her some provisions and she was informed that she could not obtain any food unless she slept there. …”

“The Porter, knowing the right well the disgraceful and unwholesome state of the casual paupers’ ward, could not, without violence to his feelings, enforce upon this destitute woman this act of cruelty; but he is moved with feelings of pity and invites her, even at the risk of dismissal from his situation, into his own room, places her by his fire, gives her a part from his own meal and when she leaves he gives her some halfpence to procure a lodging.”

The next day George Browne and Joseph Thompson inspected the workhouse and in particular, the room where the so-called vagrant women slept, and found conditions much as Ann had described them. The porter and the matron also corroborated her story. When asked about the state of the workhouse and the inappropriateness of sending a male staff member to accompany a woman to the sleeping quarters, the Master admitted the facts. He said he was aware that the accommodation was:

“inferior to that of any Union House or prison that he had seen and that he himself would rather seek rest and protection from the inclemencies of the weather under a hayrick or a hedge than subject himself to the consequences of remaining a night in the casual paupers’ ward of the Bridgwater Union House.”

George was not squeamish and despite the poor hygiene and the filth, he inspected the workhouse carefully. George and Joseph expressed their concern about the spread of cholera:

“The Tooting case cannot fail to excite alarm …. We therefore hope that the guardians will adopt some effectual measures to abate the nuisance referred to, so that the Union House may afford protection to the destitute and the population of Bridgwater may be preserved from the consequences likely to arise if the wards are suffered to remain in the state in which we found them.”

Although the written correspondence was courteous, it is likely that George was more direct when speaking to the Guardians and the workhouse staff in person.

George and Joseph went back a week later and found that some cleaning by the inmates was underway, but there was still much to be done. Over the next four months, letters went back and forth between the magistrates, the Board of Guardians and the Bridgwater Times with no further resolution. Eventually on 6 July 1849, Mayor James Haviland, George Browne and Joseph Thompson wrote to Sir George Grey, the Home Secretary. It was not a popular cause, but George Browne did his duty. History has not recorded a reply from the Home Office, but in the meantime preventive measures were overtaken by the epidemic itself. In August the same year, a tramp introduced cholera to the workhouse and from there it spread to the town. The Bridgwater Infirmary treated over 1000 patients with cholera and over two hundred people died. [31]

Final Years

The picture was very different in the 1851 census compared to ten years earlier. George was a widower, 68, living in Fore Street, and was grandly described as Captain Royal Navy, Magistrate County of Somerset, Magistrate Borough of Bridgwater, Barrister not in practice, Commissioner of Taxes and Turnpike Trust and Manager of the West of England District Bank. His sisters Mary and Fanny and brother-in-law John Bowden, along with three servants, lived with him.

In 1853 his elder sister Sophia died and was buried in the Browne family vault in the Wembdon Road Cemetery. George retired due to failing health in July 1855 and sometime after that went to stay at Brent Lodge, Bridgwater, which became the home of his younger sister Fanny (this is now the site of the Taunton Road Petrol Station). His other sister Mary Bowden and her husband John were living a little up the road in the appropriately-named Clayfield House, next to the canal. Their brother John Browne had made his first fortune from the clay at the nearby Hamp brick and tile yard. John and his family lived at Elmwood, Hamp. George died peacefully, surrounded by his family, on Tuesday 22 April 1856 at Brent Lodge.

A long funeral procession followed his coffin the following Monday. The mourners included the Mayor, Mr W. D. Bath, HM Collector of Customs Mr Hughes and many others, including his old friend, Commander John Carslake. George was buried in the Browne family vault in the Wembdon Road Cemetery with his wife Ann, whose remains had been moved there in 1853.

The Bridgwater Times published a lengthy obituary on 8 May 1856, which recounted Captain Browne’s outstanding naval career.

“We are indebted for a large portion of the materials from which this brief record of his naval life has been sketched and for the knowledge of the high estimation in which he was held, to an officer who was his messmate and companion during a period of nearly seven years of active service.”

John Carslake had known him for fifty-five years and “stood by his graveside to pay the last honour he could bring to the memory of his departed friend.” The anecdote about Nelson and the Bristol Water and George’s role in formulating the famous message in 1805 are thanks to John Carslake speaking at the funeral, as well as this one about life at sea in the years just prior to Trafalgar:

“Lieutenant Browne distinguished himself by an attention to his professional duties which has never been excelled; for two and a half years scarcely ever setting his foot on shore, except when on duty; his leisure hours were always spent in studies connected with his profession and instructing the youngsters under his care... He did nothing by halves.”

The Christian Reformer, a Unitarian magazine, also published a warm and respectful obituary, with more on his later years:

“Captain Browne, from his youth, was a Unitarian Christian … and while his health permitted, every Sunday his tall and manly figure was seen in his accustomed seat regularly twice each Sunday. … Most especially was he interested in educational movements. He was a liberal subscriber of the schools in his own town, and what was more valuable, a regular and intelligent visitor. As a magistrate his attention had naturally been called to the prevalence of juvenile delinquency … and led him to take a deep interest in efforts to establish efficient Reformatory Schools.”

The Christian Reformer went on to suggest that staying sober had contributed significantly to George’s success both in the navy and as a magistrate. He was a water drinker all his days.

“So strong was his dislike of wine or spirits that he was never known even to attempt to take any, except on one occasion, when meeting with his old friend, after a separation of nearly three years, to convince his great pleasure he exclaimed, “I’m delighted to see you; by my faith (his usual adjuration for he never swore), I’ll take a glass of wine with you;” but the latter no sooner came in contact with his lips, than the glass was withdrawn.” [32]

The main beneficiaries of George’s will were his son Samuel and daughter Marian, but he also made provision for his sister Fanny Browne. Very little is known about Fanny or her sisters. They lived quiet lives in Bridgwater, just family, friends and the Unitarian church. Fanny was blind from the age of sixty-five. She continued to live at Brent Lodge with a companion and two female servants. The latter were members of the extended Mansfield – Brabner family that between them served the Browne family for well over fifty years. Fanny died in 1871.

As a final salute to Captain George Browne, this quote from a letter to the editor is by an unnamed friend:

“Thirty years ago, I well recollect Captain Browne, then a most active, intelligent, and excellent officer. He had for years acted as signal-lieutenant on board the ships of Lords Nelson and Collingwood and he held that most trying position on board Lord Nelson’s ship the Victory, at the famed action of Trafalgar. …… to fill such a post requires the utmost nautical skill and presence of mind: the former, thoroughly to comprehend the nature of the orders that it is his business to communicate; the latter, to enable him to exercise his mind with coolness, promptitude and precision in the midst of danger, confusion and death.” [33]

Select bibliography

Clarke, John D. The Men of HMS Victory at Trafalgar including the Muster Roll, Casualties, Rewards and Medals. Vintage Naval Library. 1999. Eastbourne, UK.

Evans, Roger. Forgotten Heroes of Bridgwater. Published by R. Evans. 2000 Bridgwater.

Nelson, Horatio, 1st Viscount. The Dispatches and Letters of Vice Admiral Nelson with notes by Sir Nicholas Harris Nicolas. Henry Colburn. 1846. London. (seen on Google books.)

O’Byrne, William R. A Naval Biographical Dictionary. London. 1849.

Pappalardo, Bruno. Royal Navy Lieutenants’ Passing Certificates 1691-1902. List and Index Society c2001 Kew, Surrey. Volume 289.

Rodger, N.A.M. Naval Records for Genealogists. The Public Record Office Handbook No. 22. HMSO 1988.

Places to Visit Relevant to Captain George Browne and to the Battle of Trafalgar

Blake Museum, Bridgwater, for Bridgwater local history.

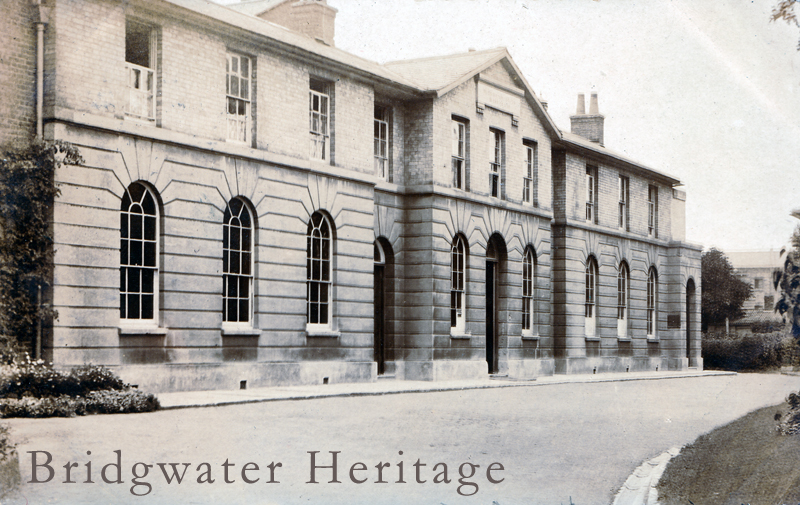

Bridgwater, Somerset. Places that George Browne knew well. The Lions, West Quay, where the parents of George Browne lived, is still standing. There are traces of the quays along the banks of the river Parrett in central Bridgwater where the sailing ships were moored in George’s day. You can walk along Cornhill, where George lived above the bank from about 1835 and along Fore St where he lived in the 1850’s. The Magistrates Court where George Browne worked, the County Court and the Assize Court (the Town Hall) have all survived.

Christchurch Unitarian Chapel, Dampiet St, Bridgwater.

National Maritime Museum, Royal Museums Greenwich – holds George’s Naval General Service Medal with Trafalgar clasp (rt6985), his compass rx1589 and pocket compass rw1998. The online catalogue has photos of these items.

National Museum of the Royal Navy, Portsmouth. HMS Victory has been conserved and usually visitors can walk around the ship and see where George Browne, as well as Admiral Nelson and Captain Hardy and the crew, lived and worked. (See website for times and details of access.)

Nelson’s Column and Trafalgar Square, London. These are famous landmarks.

Somerset Heritage Centre, Taunton. Somerset Archives holds the Bridgwater Times for the year George died as well as Borough of Bridgwater historic documents.

The National Archives, Kew. The National Archives holds the Admiralty and Home Office documents referred to in this biography. If you wish to see George Browne’s log from HMS Victory, it is necessary to order it online in advance. You will need a reader’s ticket and expect to be supervised by staff when you are handling these documents, as they are national treasures.

Wembdon Road Cemetery, Bridgwater. George Browne memorial on the side of the Browne family vault.

On-Line Resources

Most of the places listed above also have websites.

Bridgwater Heritage Group. Online research for a Somerset Town.

British Newspaper Archive

Friends of Wembdon Road Cemetery. This website has biographies and obituaries, burial registers and photos of the memorials.

Genealogy websites – forparish registers, non-parochial registers, census records etc.

Images of the funeral of Admiral Nelson. George Browne was one of the lieutenants standing close to the coffin, so may be depicted in illustrations.

Private collections – items held in private collections are sometimes described online by the auction house when they are for sale. Sotheby’s advertised George Browne’s sea-chest with a photograph in 2012. [34] Bonham’s auctioned a letter George wrote in 1845, with a photo of the last page. [35]

Appendix A

Appendix B

[1] The reference to being a merchant of The Lions is from the notes of Harry Frost. The street is now called West Quay. One report in the Wells Journal, 10 May 1856, suggests that William Browne the father was also an exciseman, but this has not been confirmed. William may have been collecting taxes for the Borough of Bridgwater, rather than working for the Excise Dept.

[2] George’s date of birth is from Royal Navy records.

[3] Roger Evans quoting family records. Forgotten Heroes of Bridgwater, p 108. The school referred to was probably the King James Grammar School which was founded in 1623.

[4] Roger Evans. Forgotten Heroes of Bridgwater, p 108. The Captain of the Royal George was Captain Domett, later Admiral Sir William Domett (1752-1828) who had a distinguished career, including seven years in command of HMS Royal George.

[5] Thorne R., editor. The History of Parliament: The House of Commons 1790-1820 1986. Seen on the website of the History of Parliament Trust. The History of Parliament, Member Biographies.

[6] Only a very select few young gentlemen, the Admiralty nominees, were trained at the then Royal Naval Academy.

[7] Commander John Carslake Royal Navy (1785-1865), later a JP in Sidmouth, Devon.

[8] It is not clear why George’s time in HMS Boadicea was not mentioned on the 1804 documentation for his Lieutenant’s passing certificate. Instead, it refers to George being aboard the Royal George for three years. There may be an administrative reason for this, or alternatively just oversight.

[9] HMS St George did not have a prominent part in the Battle of Copenhagen. Admiral Nelson was on board HMS Elephant which was better suited to shallow waters. It was at the Battle of Copenhagen that Admiral Nelson, second in command, put his telescope to his blind eye and said, “I really do not see the signal”. The signal, which had already been reported to Nelson was from his Commander in Chief telling him to retire from the battle.

[10] ADM 6/102. 1804. Lieutenant’s passing certificate in the National Archives, Kew. The three examiners were: Admiral Sir Richard Goodwin Keats (1757-1834), in 1804 was Captain of HMS Superb; Admiral Sir Robert Barlow (1757-1843), in 1804 was Captain of HMS Triumph; Captain Richard or Robert ….ham(?)

[11] Officially a midshipman had to be aged twenty or older to be promoted to Lieutenant, but this was ‘honoured more in the breach than the observance’ - so long as he’d done his six years’ ‘sea time’ - then, he could get promoted to Lieutenant before that age - as Nelson was, for instance.

[12] The Dispatches and Letters of Vice Admiral Nelson. Letters ccxxxiii

[13] Roger Evans. Forgotten Heroes, p 110.

[14] HMS Victory. Lt George Browne’s log. The National Archives ADM 51/4514.

[15] The stories of the Bristol Water and the Buona Ventura are both from Roger Evans’ Forgotten Heroes.

[16] Newspaper accounts, such as in the Wells Journal 1856, quote an unnamed good friend of George Browne. The usually accepted account is that Nelson originally dictated to Lt. Pasco (not George Browne) ‘England confides every man …’ but agreed to the substitution of ‘expects’ instead of ‘confides,’ because the word expects was quicker to send with the signalling flags.

[17] O’Byrne’s Naval Dictionary.

[18] Sugden, John. Nelson: The Sword of Albion. Bodley Head. 2012. Page 802. Many, many books and articles have been written about Admiral Nelson and the Battle of Trafalgar, which was a decisive victory for the British. This is just one of just a couple of named references to Lt. George Browne.

[19] The Dispatches and Letters of Vice Admiral Nelson. Vol 7. Aug-Sept 1805. p178.

[20] From the description of George Browne’s sea-chest by Sotheby’s in 2012. (#20) Battle of Trafalgar--Browne, Lieutenant George. (sothebys.com)

[21] Extract of a letter from Lord Collingwood to Lord Mulgrave, 22 February 1810, vide “Life and Correspondence of Lord Collingwood”, folio 560. Seen in the Western Times, Exeter, Devon. 17 October 1840. Lord Mulgrave (1755-1831) was First Lord of the Admiralty from 1807 to 1810.

[22] ADM 9/4 p1052. (1817) Survey returns of officers’ services. In 1817 the Admiralty sent circular letters to officers, including those on half pay, requiring them to supply a summary of their naval careers. Captain George Browne was one of the officers who sent in a comprehensive list of the ships in which he served and this has been preserved in the National Archives. A summary forms Appendix B. The catalogue description on the Trafalgar Ancestors website (TNA) refers to a caricature on this document. It is a small cartoon of a man brandishing a sword, designed to draw the eye to the place on the page where HMS Victory and Admiral Nelson are listed. Then there is a second identical page but without the cartoon. In those days before photocopiers, it is probable that an Admiralty clerk drew the cartoon but was then required to copy out the page again. The original letters from the officers appear not to have been kept, just the transcription in a standard format on pre-printed pages.

[23] George’s farm was probably Knowle Hill Farm, between Puriton and Bawdrip, close to Bridgwater, but this has not been confirmed. His 1814 marriage licence states he was a bachelor of the parish of Puriton and his children were born at Puriton, which makes Knowle Hill Farm likely. There were other locations in Somerset of the same name, including the Knowle Hill just west of Taunton.

[24] The Inner Temple library was badly damaged during WWII, but the Archives of the Inner Temple website: Inner Temple Collections gives the dates of George’s admission and call to the bar.

[25] The Wells Journal of 10 May 1856, shortly after George’s funeral, reprinted an article from the Bristol Times which quotes an unnamed friend. It states that George “was brought to the chambers of the present Mr Commissioner Hill, by a friend, for the purpose of being introduced to a bencher.” In 1856, Matthew Davenport Hill (1792-1872) was Commissioner of Bankrupts for Bristol. He was also a pupil barrister in London at the Inns of Court about the same time as George Browne and had a distinguished career as a barrister and an MP.

[26] Western Times, Exeter. 17 October 1840.

[27] Bridgwater 3 Oct 1845. From the website of Bonham’s auctions 2005.

“Emily is very unwell all the rest are nearly as you left. I have requested our mother write to you by this post therefore I rely on her filling up what I have omitted. Mrs Spiller still in Wales – good remittances this journey. I remain my dear Samuel, Yours ever George Browne.” Bonhams: George Browne Lewis, Second Signal Lieutenant of HMS Victory

[28] Western Times, Exeter. 17 October 1840. The identity of Nauticus is unknown.

[29] His medals are now in the Royal Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.

[30] The following quotes are from the copy of correspondence in the National Archives. HO 45/2973.

[31] TNA HO 45/2973 George Browne and the Mayor escalated the incident to the Home Secretary, Sir George Grey (1799-1882) and thus a copy of the correspondence is in The National Archives, Kew. The first letter to the Board of Guardians is dated Thursday 15 February 1849 and refers to events on Friday 9 February. No reply has been found as yet.

[32] The Christian Reformer or Unitarian Magazine and Review, edited by Robert Aspland New Series Vol XXII. Published by Edwin T. Whitfield, London, 1856. The Christian reformer; or, Unitarian magazine and review [ed. by R. Asplan... - Google Books

[33] Western Times, Exeter. 17 October 1840. The identity of Nauticus is unknown.

[34] Sotheby’s Description of George Browne’s sea-chest from HMS Victory. George III pine chest (h. 51cm, w. 80cm, d. 41cm), the hinged lid with later strengthening cross-pieces and lettering ("Herbert M. Thompson"), decorated with prints of four animals glued to the underside, enclosing a later removable zinc tray, zinc lining, remains of painted metal handles to the sides, with a woollen blanket covering, later embroidered with the signal "ENGLAND EXPECTS EVERY MAN WILL DO HIS DUTY", decoration refreshed

Provenance: George Lewis Browne (1784-1856); his daughter Marian Thompson; her son Herbert M. Thompson (who refitted the chest for use on his honeymoon tour of Japan); direct family descent.

(#20) Battle of Trafalgar--Browne, Lieutenant George. (sothebys.com)

[35] Bonhams auction in 2005. GEORGE BROWNE LEWIS, SECOND SIGNAL LIEUTENANT OF HMS VICTORY Autograph letter signed ("George Browne"), to his son Samuel W. Browne, discussing family news, 3 pages, 4to, Bridgwater, 3 October 1845. An offprint of the obituary of Captain George Lewis Browne (1784-1855) from the Bridgwater Times is included in the lot. Bonhams: George Browne Lewis, Second Signal Lieutenant of HMS Victory

Inscription on memorial in the Dampiet Street Unitarian Chapel:

In memory of George Lewis Browne, Captain Royal Navy, and of Ann his devoted and beloved wife, this tablet is erected by their sorrowing children who affectionately cherish as their best heritage the consolatory remembrance of their parents bright example in every relation of life. During many years active service Captain Browne obtained the trust and highest commendation of Admiral Lord Nelson under whose immediate command he distinguished himself at the Battle of Trafalgar. After the restoration of peace he became barrister of law of the inner temple and subsequently a magistrate for the county of Somerset. He was born 15th January 1784 and died 22nd April 1856. His wife, daughter if Thomas and Ann Pyke of this town was born 9th December 1781 and died 25th October 1846.