Sarah Ann Harris (1853-1858) daughter of Isaac Harris and Mary Harris.

Mrs Mary Ann Harris nee Jolliffe (1821-1882), first wife of Isaac.

Mrs Emma Harris (c1836-1898), second wife of Isaac.

by Jillian Trethewey, Hilary Southall and Clare Spicer 14/6/2022

Isaac Harris was a shoemaker of Friarn Street, Bridgwater.

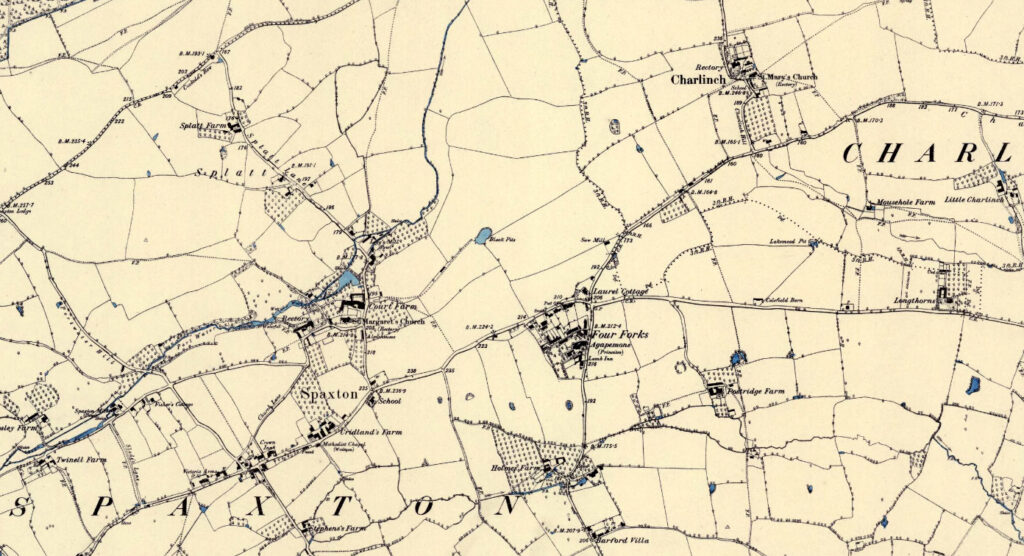

Isaac was baptised on 9th March 1823 in the village of Charlynch, about five miles west of Bridgwater. His parents were Joseph Harris, a journeyman stonemason, and Jane nee Bishop. Jane died in 1824 leaving Harriet, 6, Charles, 4 and Isaac, about 18 months. Six months later Joseph married Sarah Breffit. He would not have been expected nor encouraged to look after the house and children himself. Joseph and Sarah had six more children.

Joseph and his family moved to the village of Fourforks in 1827. It was just across the parish border with Spaxton in picturesque Somerset countryside. But unemployment in rural areas was rising and by 1840 villagers were increasingly moving to towns to find work. Isaac left Fourforks at about the age of fourteen and didn’t live there again. He was apprenticed to Bridgwater Master Shoemaker Robert Tapscott (1810-1850). The 1841 census shows Isaac Harris, 18, and fellow apprentice John Comber, 18, living with the shoemaker and his family in St Mary St, Bridgwater. The Tapscott family were Baptists, suggesting that the Harris family may also have attended a Baptist or Wesleyan or Congregational Chapel when they could, as religion was very important then.

In 1844 Isaac turned twenty-one. He had finished his apprenticeship and wasted no time in marrying Mary Ann Jolliffe on 26th May at Holy Trinity Parish Church, Bridgwater. Mary was two years older than Isaac and had already had a hard life. She was the daughter of a single mother and both she and her mother worked as servants. In March 1841, Mary Ann became a single mother too with the birth of her son John Edward Jolliffe. Mother and baby were still in the Bridgwater workhouse when the census was taken three months later. There were very few options for a woman too pregnant or too ill to work, if she had no family to provide support. John Edward died aged ten months in January 1842, still in the workhouse.

Isaac may have completed his apprenticeship, but most journeyman shoemakers as he was now called, worked for some years before becoming a master. At the same time, the guilds that regulated skilled trades were gradually losing their power. Isaac may have become a master shoemaker but there is no evidence in the census that he employed apprentices.

In the 1851 census, Isaac was described as a Master Cordwainer of Friarn Street. In the following decades Isaac was a shoemaker of Friarn Street. He and Mary had four children of their own: Elizabeth born in 1845, Walter in 1849, Sarah (1853-1858) and Albert born in 1858. They lived above the shop. Isaac earned enough to provide for his family all year round and pay for apprenticeships for his sons when the time came. However the number of shoes he could make and sell was limited by the hours in the day. Any town had many shoemakers so if Isaac raised his prices, people could go elsewhere.

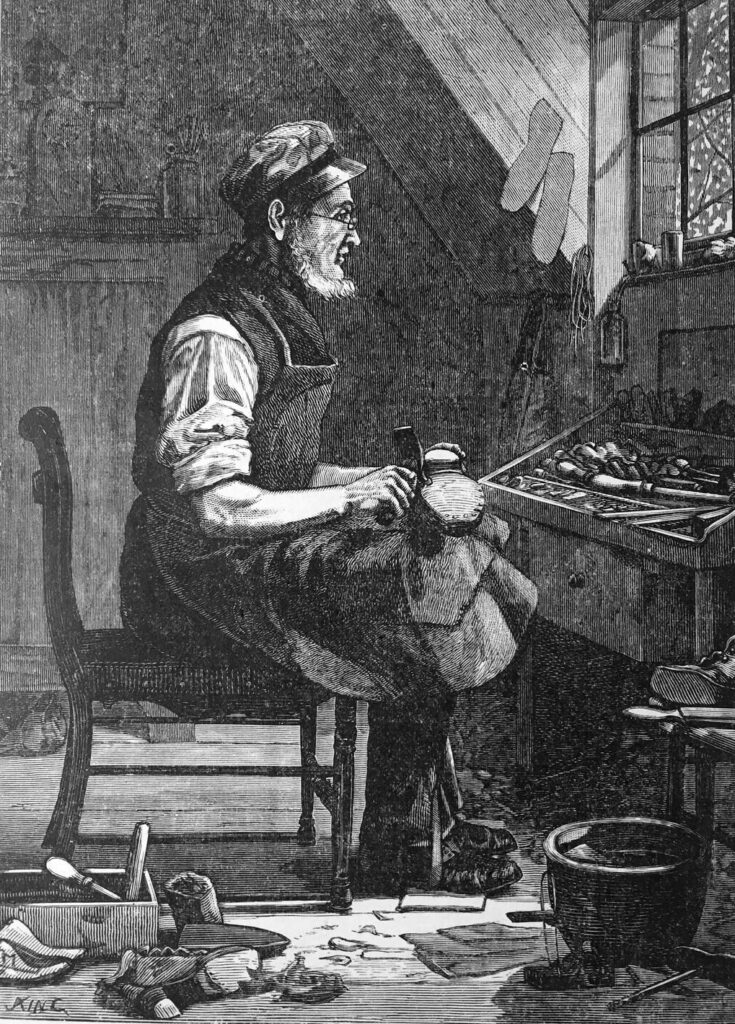

Shoemakers worked primarily with leather to make and repair boots and shoes. Traditionally a cordwainer worked with the finest leather imported from Cordoba, Spain. Centuries later, hides came from the local tanner, but still a shoemaker was called a cordwainer. A cobbler was trained to repair boots and shoes. Workmen’s boots were big and heavy and made with thick leather. The finest shoes made in London and Paris had silk uppers, but leather uppers were more common for ordinary people for everyday wear, just thinner leather for women and children.

Each shoemaker had his own set of leather-working tools and the special wooden lasts of different sizes. Straight lasts were still used in Isaac’s day, so there was no left and right shoe until worn in and the leather moulded to the person’s feet. Breaking in a new pair of shoes was not easy. There were also no lasts of different widths as a master shoemaker would measure the foot with a size stick and then pad the standard last as required. Tools used by shoemakers included awls for punching holes in leather, sole knives to shape soles, stretching pliers to stretch the leather uppers, marking wheels to mark where the needle should go through the sole and burnishers that rubbed the leather to a shine. There were three basic tasks: cutting leathers, sewing uppers and joining the heel to the sole. In a big shop or factory these were done by different people, but Isaac probably did it all himself, perhaps with Mary and the children helping.

Mrs Mary Harris died in January 1882 and was buried in Wembdon Road Cemetery. She was fifty-eight. The burial service was conducted by the Congregational minister, Rev. E. J. Dukes.

Isaac waited the proper twelve months before he married Mrs Emma Coles in March 1883 at Holy Trinity Parish Church, Bridgwater. Emma was a widow aged forty-seven. By 1891 they had moved to Penel Orlieu, Bridgwater. Isaac died in January 1895 and Emma in 1898. Both were buried by the Congregational minister in the Dissenters’ section of Wembdon Road cemetery. Isaac must have dutifully married in the parish church both times, but also attended the Congregational Church.

Sarah Ann Harris daughter of Isaac and Mary, buried 18th May 1858 aged 4 ½, in grave 118.

Mary Ann Harris nee Jolliffe, first wife of Isaac, buried 14th January 1882, aged 58, in grave 118

Isaac Harris buried 24th January 1895 aged 71, in grave 118

Emma Harris, second wife of Isaac, buried 5th May 1898 aged 62

Of Isaac’s three surviving children, Elizabeth became a dressmaker and Walter and Albert both became harness-makers, so also working with leather. Albert (1858–1897) was apprenticed to Mr Plowman, saddler, and became a saddle and harness-maker in St John Street. He was married with two children when he died in Bridgwater aged thirty-nine.

Sources:

Census records and parish registers. Primarily from Ancestry.