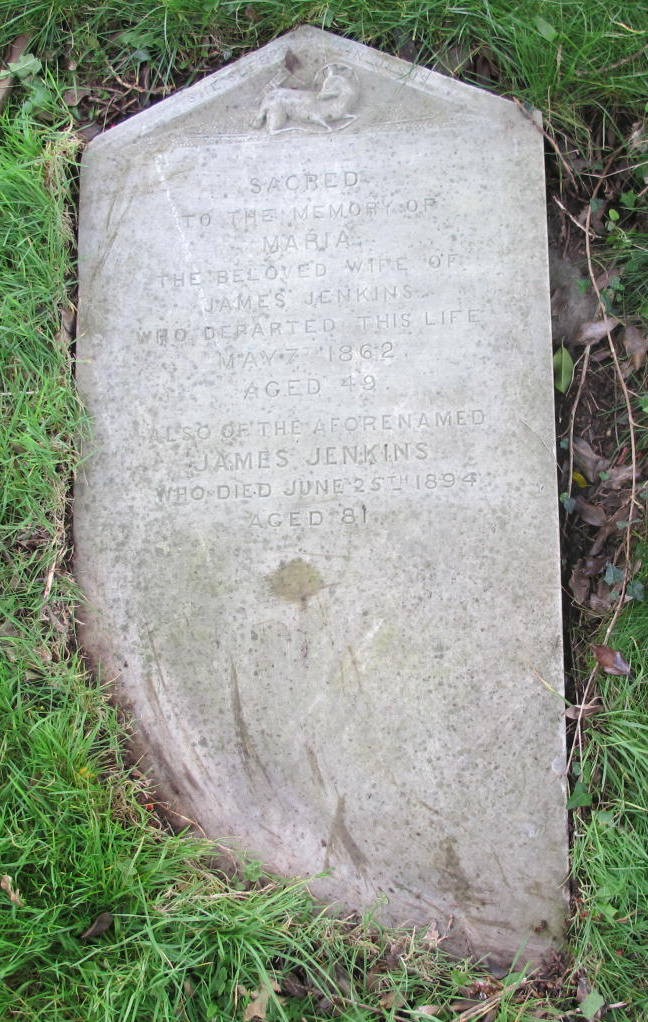

James Jenkins was buried on 30th June 1894, aged 81. Maria Jenkins, his first wife, was buried on 12th May 1862, aged 49.

by Jillian Trethewey, Hilary Southall and Clare Spicer 28/7/2022

James Jenkins was a Bridgwater butcher and Baptist deacon, a farmer at Durleigh, then a grazier and cattle dealer of Dean Villa, Wembdon.

James was born in Bridgwater about 1813, but his baptism, possibly in an Independent Chapel, has not been found.[1] Then when James married in 1834, he was recorded as being a widower, which is also unexplained.[2]

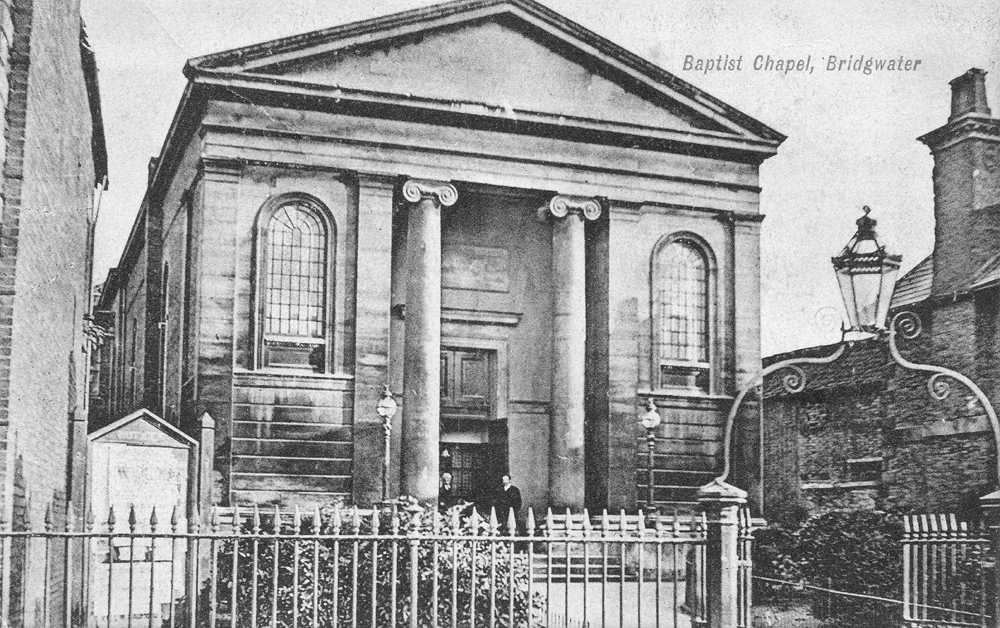

James Jenkins married on 29th September 1834 at St Mary’s Parish Church, Bridgwater, to Maria Sainsbury. Marriages conducted by non-conformist ministers were not permitted until 1837, so James and Maria probably worshipped at either the Baptist or the Independent Chapel, despite marrying at St Mary’s. Maria’s parents were John Sainsbury, a Bridgwater stonemason, and Mary nee Manning. Maria’s siblings later married in either Baptist or Independent ceremonies.

In 1839 James was a butcher in Back Lane, Bridgwater, now Clare Street.[3] The 1841 census records James, Maria and their two daughters Mary, 7, and Sarah aged 3 months living above the butcher’s shop. Also at the same address in Back Lane were Maria’s brother James Sainsbury, 15, apprentice, another young butcher and a maid.

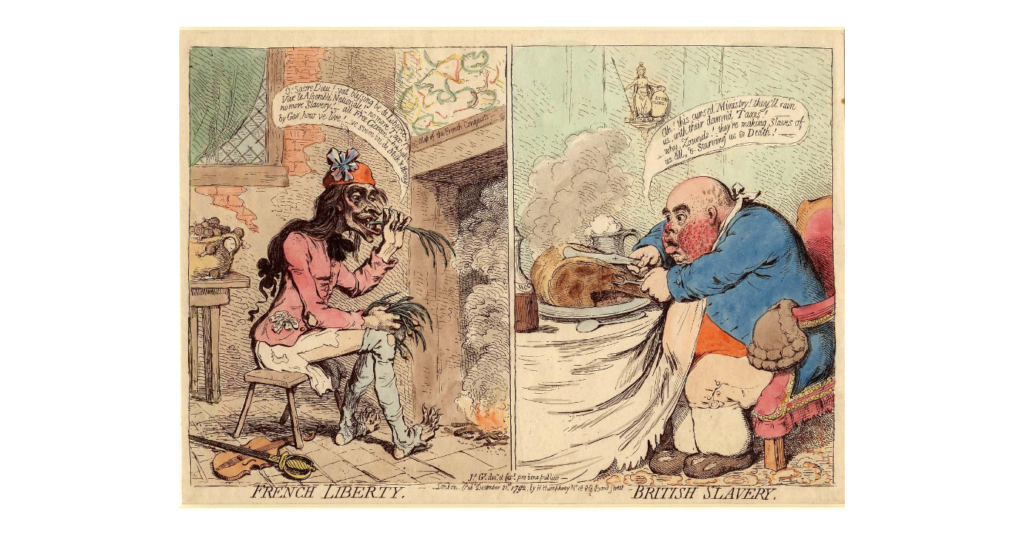

Eating meat was popular in the Victorian era and in 1842 Bridgwater had ten butcher’s shops, plus Thomas Newton in North Petherton. The better off enjoyed roasting joints for Sunday dinner. The more affordable cuts of meat, bones and salted fat were within budget for ordinary people to add flavour to soups and stews. There was no refrigeration and although salt could be used as a preservative, usually the housewife went to the butcher’s shop in the morning to buy meat to cook that day or the next.

But for the butcher and his family, there was no escape from the smells of the animals and the meat. Even in towns, butchers usually purchased sheep and cattle at the local market and then drove them through the streets to a slaughter-house at the rear of their shop. A public abattoir, built by the Borough of Bridgwater and then rented to butchers, was discussed probably every time a resident complained in a letter to the editor of the “nuisance” from a neighbouring slaughter-house. One borough inspector observed that many of the slaughter-houses were very old, badly situated and cramped for space. When overcrowded each year with calves, butchers used other premises as temporary slaughter-houses which contravened sanitary regulations and made things worse. [4]

James and his first wife had a daughter Mary, then James and Maria had eleven children. The Bridgwater Independent (Congregational) registers of baptisms have not survived, but birth certificates began in 1837 and the census records of 1851 and 1861 show the Jenkins family growing. The nine children who survived infancy were Mary (1834), Sarah Maria (1841), Frederick (1842), Lucy Dickenson (1844), Fanny (1848), Elizabeth or Bess (1849), Ellen (1850), James (1852) and Annie (1854). By 1851 the family had relocated to a butcher’s shop in High Street and there were three live-in servants to help Maria as well as two apprentice butchers to assist James.

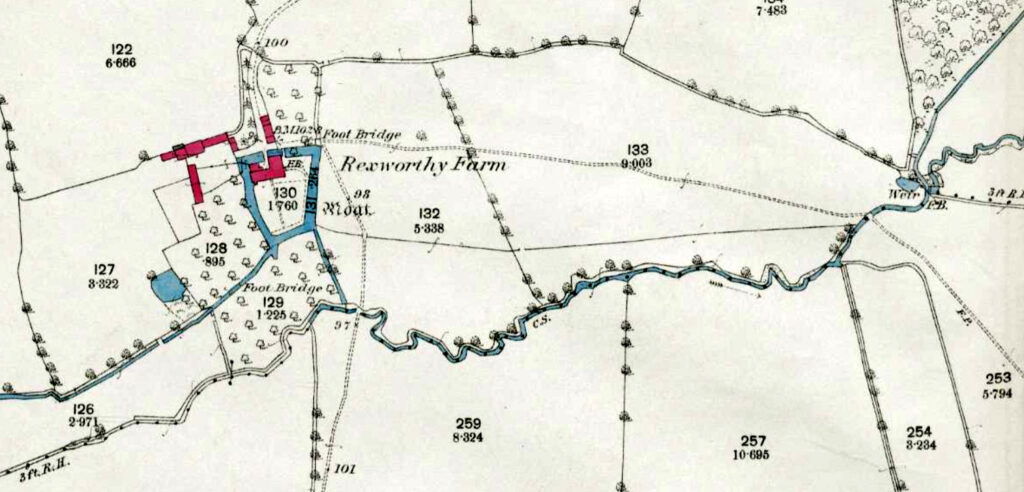

Sometime after the birth of Annie, the Jenkins family moved to Rexworthy Farm, Durleigh, three miles west of Bridgwater. James became a tenant farmer of 140 acres employing three labourers and one boy. Maria had one housemaid, but expected her daughters to work in the home too. The eldest, Mary, married William Hawkes, a grocer of Devonport, in February 1860 at the Baptist Chapel in Bridgwater.

It is surprising to learn that James was a Baptist deacon and was also involved in the election fraud that was widespread in Bridgwater at the time. The Court of Queen’s Bench sat in Bridgwater on the 11th May 1859 to hear two related cases of “criminal information”, Reed v. Heard and Jenkins v. Bragg. In the first, Henry Clement Heard, a chemist and druggist, proprietor of the Bridgwater Times and Somerset County Chronicle, had allegedly published a libel on Mr Reed, a gentleman of nearby Burnham-on-Sea, accusing him of wholesale bribery at the recent election, in favour of Colonel Tynte and Mr Alexander W. Kinglake (Liberal party). Mr Reed denied this. The prosecutor, Mr Smith Q.C., read from the newspaper: “At the last moment, and when terror and dismay were evidently depicted upon the face of the Liberal party, ... a friend in need came forward … and brought into the Liberal camp the sinews of war. The news soon spread. An office for the purchase of votes was opened in a slaughter-house, at the back of a butcher’s premises, and we are told that a man of the name of Jenkins, a Dissenter, and deacon of a Baptist Chapel, formerly a butcher, and now a small farmer, was installed as cashier. A band of supernumeraries, radicals, Scotchmen, Dissenters, and some, we are told, even professing preachers of the Gospel, ran about among the venal electors and drove them into the slaughter-house, where they were knocked down at the rate of £25 a head, to forfeit their promise to vote for Messrs Padwick and Westropp, and were driven to the poll to vote for Colonel Tynte and Mr Kinglake.” In the second case, the defendant, William Bragg of Taunton, proprietor and publisher of the Somerset County Herald, had allegedly libelled James Jenkins in the same way. The claims against the two men were “great and scandalous charges” and the justices agreed both cases should proceed to trial. Ten years later the Bridgwater Election Commission investigated entrenched corruption and called hundreds of witnesses, including James. There was likely some truth in the allegations made in the newspapers, as many similar incidents involving hundreds of Bridgwater businessmen were revealed by the Commission. James stated that the charges against William Bragg were withdrawn for political reasons. [5]

To a butcher, having his own herds of sheep and cattle, as well as plenty of space for his family, must have sounded wonderful. Rexworthy Farm was still close enough to Bridgwater for church, shopping and visiting friends. But James and Maria were only happy there for a few years. In April 1860, James auctioned off some livestock. In April 1862 he advertised that the farm was available to be let. No reason was given, but for any farmer, a bad season could mean trouble paying the rent and so the need to raise money. Or James may have found that the farm was too big for his needs or that with his wife Maria ill, it took up too much of his time.

Mrs Maria Jenkins died aged 49 and was buried in Wembdon Road Cemetery on 12th May 1862. The service was conducted by the Baptist minister, Rev G. McMichael.

James sold up by auction on the 23rd March 1863 and there was a detailed description of his livestock and farm equipment in the newspaper.

James moved to Dean Villa, Wembdon Rd, in the parish of Wembdon but still close to Bridgwater. Directly behind Dean Villa was Wembdon Brewery and behind that again, James had a large L-shaped field in which he could hold or fatten cattle.

James was forty-eight when he married again. Mrs Amelia Baker, nee Newick, was forty-one, of Redcliff, near Bristol and was the widow of a carpenter. Her father, John Newick, had been a publican in Redcliff. James and Amelia married at the Zion Congregational chapel, Coronation Road, Bedminster, on the 26th March 1864.

In December that year James had to call the police because £84 in notes and gold was missing, presumed stolen. James and Amelia had gone to church on Sunday, leaving behind a housemaid to care for a young niece. As usual, James told the maid to keep the doors locked as it was a somewhat lonely location. The maid’s story was doubted later, but she said she heard footsteps in an upstairs room and went to investigate. She saw a man running from the house, so the maid ran to the neighbours for help. When James returned, he found that the money and valuables were missing from a locked draw, which had been chiselled open. Nothing else was taken. Superintendent Lear of Bridgwater Police arrived and was immediately suspicious that the maid was the thief, because a professional would have taken the cashbox and other items. After the police left, James offered the maid £5 and promised that he would not press charges, if she would return all the money. The next morning there was a thorough search of the house and the maid found the money under the pump trough in the yard. James kept his word and the maid was free to look for employment elsewhere. James saved her from a likely prison sentence.

James was involved in several court cases in the years to come as both plaintiff and defendant. In 1866 James won costs from a man who knowingly sold him a sick horse.[6]

On the 25th July 1867 James was in court in Bridgwater as a defendant answering two unrelated charges on the same day. The first case related to non-payment of rates. It was a new lighting and watching rate and James claimed that he, along with probably most residents, knew nothing about it. The magistrates ordered him to pay the 15 shillings. In the second case he was charged with infringement of cattle plague orders. [7] James had moved two cows from Moorlinch to Wembdon without first obtaining the necessary permit. He was fined 40 shillings. James: “I think it is a very hard case.” Magistrate: “You must consider yourself very fortunate that you are not fined £5.”

Twelve months later, James Jenkins, of Wembdon, was summoned by Mr. McDonald, Inspector of Nuisances, for allowing a nuisance to exist on his premises, in St. Mary-street, Bridgwater. This may have been another butcher’s shop sub-let. The nature of the nuisance was not stated and so probably related to a cesspit. James was ordered to resolve the nuisance (empty the pit) and pay costs. James went back to court the following week to complain that the costs were excessive and was ordered to pay an additional seven shillings for non-compliance.

In February 1871, James, now a cattle dealer of Dean Villa, took a local farmer to court, because the sheep James had purchased from him were diseased and either unusable due to liver flukes or sold on as pig meat. But it was buyer beware and James lost the case.

The Inspector of Nuisances was even needed in the countryside and James must have felt he was being targeted. A meeting of the Rural Sanitary Authority was reported in the Bridgwater Mercury on the 3rd October 1877. As more new houses were being built and the population of Wembdon grew, the existing arrangements for sewage were no longer satisfactory. “The evil has increased” announced the Mercury. “The overflow of cesspools has found its way into the rhines (open drains) … of Wembdon Level and in these the surface accumulation has been so great as almost entirely to obstruct the flow of the surface drainage into the river (Parrett).” At times the otherwise pleasant short-cut across the fields from Bridgwater to Wembdon Church was spoilt by the stench from the rhines. An engineer had been employed by the Authority to draw up plans for drainage works to resolve this, but people were getting impatient. However the Authority’s inspector, Mr Toogood, had found two areas where improvements could be made quickly. The nuisance in the rhine adjoining Wembdon Drove and alongside Chiltern Rd [Chilton Street], was caused by sewage from the houses called “Zig-Zag Row” and other houses close by, all of which were in the borough. Mr Parker, the borough inspector, had promised to take steps to resolve this. Mr Toogood had inspected another nuisance in Wembdon. Near the cemetery were eight dwelling-houses and a slaughter-house, the former having a cess-pit, the overflow from which formerly ran into a pit in fields occupied by Mr Jenkins and Mr Walters.[8] Since his first visit, the owners of the houses had removed the overflow drain, so that no more sewage could escape from the cesspit. Mr Toogood had given Mr Walters notice to provide a catch-pit for his slaughter-house and to clean out the pit in his field. He had also given Mr Jenkins notice to clean out the pit.

Despite several court appearances, on one occasion James was unrepresented and unprepared for an encounter with a defence lawyer. It was September 1878 and the Jenkins’ maid was looking out of a bedroom window at Dean Villa, when she saw a man picking apples in the garden. She alerted James and identified the man as Thomas Pulsford from the Wembdon Brewery, only two doors away. In court, two brewery workers testified that Thomas was in the engine-house at the time specified. James accused them of being accessories. It was also revealed that James had offered his maid a sovereign if she could identify the intruder by name, thus casting great doubt on her reliability as a witness. Another worker said James had offered him a sovereign too. James Jenkins: “This witness is another accomplice.” The magistrates said they could not permit such accusations to be made and Mr Chapman, the defence lawyer, remarked: “Mr Jenkins is very fond of asserting what he cannot prove.” James Jenkins: “I did not suppose that you would bring people here to swear what is false.” Mr Chapman: “If you say that again I’ll make you answer for it elsewhere.” The case was dismissed.[9]

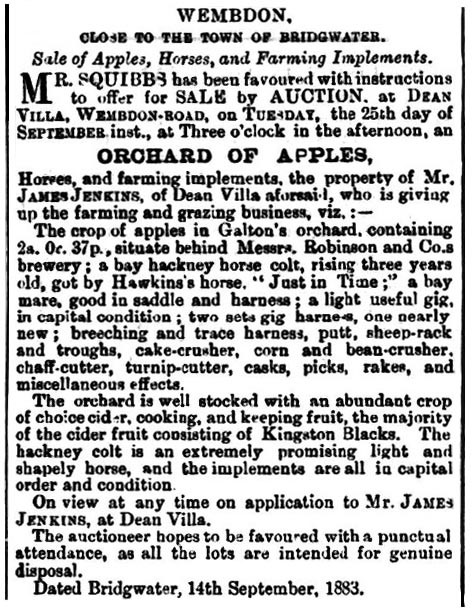

In September 1883, James was retiring as farmer and grazier. “Galton’s Orchard”, about 2 acres at Wembdon, and “Chaffey’s Meadow” about 4 acres and numbered 418 and 424 respectively on the Tithe map, were advertised to let for terms of 3, 6, or 9 years. [10]

James died on the 25th June 1894 at Dean Villa, Wembdon, aged 82 years. He was buried in Wembdon Road Cemetery with his first wife Maria. Her mother, sister and brother-in-law are buried in an adjacent grave.

James had twelve children:

- Mary Jenkins b c1834 who married Devonport grocer William Hawkes.

- John Sainsbury Jenkins (c1836-1839)

- Frederick Jenkins (1838-1841)

- Sarah Maria Jenkins b c1841, a National school-mistress, who in 1911 was retired and living in Devonport with her niece Annie Stephenson.

- Frederick Jenkins b 1842, still at home in 1861.

- Lucy Dickenson Jenkins (1844-1870) married William Matthews in 1869 in Devonport.

- Emma Jenkins born 1845, died young.

- Fannie Stowe Jenkins (1848-1921) married in 1876 at the Baptist Chapel, Reuben Stephenson, manager of the National Provincial Bank of England, Devonport.

- Elizabeth, called Bess, Jenkins born in 1849 and married in 1878 at the Baptist Chapel to Walter Glanfield of Salisbury.

- Ellen Jenkins born 1850, married in 1871 William P. Morell, Post Office Superintendent, Plymouth.

- James Jenkins born 1852, army grocer of Portsmouth and an executor in 1894.

- Annie Jenkins born 1854 who married in 1880 in the Baptist Chapel to George Venn.

Probate was granted to his widow Amelia and his son James Jenkins, army grocer of Portsmouth. He left £281. This included a Policy of Assurance with the National Provident Institution for two hundred pounds to pay his funeral and testamentary expenses.

Amelia went to live at Plymouth Hoe in a boarding house. She had at least four step-children living in Plymouth and Devonport. The 1901 census recorded that she was feeble-minded. She died in Devon in 1902.

SOURCES

British Newspaper Archive

Census records, Directories and Parish Registers.

Will of James Jenkins.

[1] Not every register of baptisms has survived, especially those of non-conformist churches or chapels. On his 1864 marriage certificate, James stated that his father was Jeffery Jenkins, but no record of Jeffery has been found in Bridgwater as yet either.

[2] Jenkins is too common a surname to identify an earlier marriage with any certainty. His eldest child, Mary, who was born about 1833 or 1834, may have been from his first marriage. Maternal deaths from childbirth were frequent.

[3] Robson’s Directory of Somerset 1839.

[4] Bridgwater Mercury. 25 Aug 1886.

[5] Bridgwater Mercury. 18 May 1859. West Somerset Free Press, Minehead. 16 Oct 1869. James testified that in 1859 he brought an action for libel against Mr Bragg of Taunton, in whose paper was published a statement to the effect that James had bribed sixty voters in Newton’s slaughter house. It was not made clear whether James was sent to Taunton for the day as a clandestine cashier. Newton’s slaughter-house was in Taunton, but perhaps there was one in Bridgwater too.

[6] Western Gazette, Yeovil. 12 Jan 1866

[7] In 1865-1867 there was a serious outbreak of cattle plague, caused by the Rinderpest virus, in England.

[8] Robert Walters was a butcher in Bridgwater, who later retired to Wembdon.

[9] Somerset County Gazette, Taunton. 28 Sept 1878.

[10] Somerset County Gazette 15 Sept 1883