George Crocker 1836 – 1919, Emily Rhoda Crocker nee Morris 1846 – 1899 and Horace George Reginald Crocker 1868 – 1895

Clare Spicer, Hilary Southall and Jill Trethewey 21/02/2022

George Crocker was born and brought up in Bridgwater, and spent all of his life there. He came from a family of thatchers and farm workers in the nearby village of Bawdrip, but George followed a very different path. From childhood he witnessed the rapid population growth in Bridgwater during the mid-19th century, and the poverty and hardships that came with it. George worked as an accountant and administrative clerk to the Poor Law Union.

George Crocker’s early life

George was baptised on the 3rd of January 1836 in St Mary’s Church, Bridgwater. He was the eldest of three sons of James Crocker and his wife Sarah nee Rugg. George’s father James worked as a post boy, accompanying and guarding mail bags as they were distributed from the central post office in Bridgwater to surrounding areas. The family lived for over 20 years in Back Street, (now Clare Street), which is a road parallel to the High Street. This was a busy road in the centre of town.

By the census in 1851, George had left school and found work as a clerk, while his younger brothers John and Frederick were still listed as scholars. The properties next to their home were a stable and a blacksmith’s shop, which would have been both noisy and smelly.

Ten years later in 1861, the family were living over the bar of a pub in Back Street, as George’s father James had changed occupation and become an innkeeper, probably of the Cow and Butcher pub. Although George, now aged 25, was working as a solicitor’s general clerk, he and his two younger brothers would have had to roll up their sleeves and help in the pub in the evenings.

George had plenty of opportunities to meet his future wife Emily Rhoda Morris, daughter of the saddler William Morris and his wife Mary Ann nee Bryant, as her family lived in Angel Crescent which was a small road running in to Back Street. George and Emily married in 1867, and a year later they had their son and only child Horace George Reginald Crocker. (Horace was known as George). By 1871 they had set up home in Dock Road, next to Russell Place. Their son George was aged 3, and a 2 year old nephew called Willie Evans was living with them. The two little boys probably had a lot of fun playing together.

As well as being a solicitor's clerk, he was also the managing clerk to the clerk of the Poor Law Union. This meant that he was the senior administrative assistant to the Clerk for the Board of Guardians, Mr Paul O H Reed. George is mentioned in Reed's obituary of 1903 as one of the staff in his firm, which was Reed and Cook.

Board of Guardians for the Bridgwater Poor Law Union

Before 1834, the work of distributing relief to the poor was done by each parish, which might have a small ‘poor house’ but also would distribute money, food and clothing to people in their own homes as the parish officials thought appropriate. The Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834 combined groups of parishes into poor law unions. Each union was to have a workhouse to which the poor were sent, and the regime was designed to be very harsh with the express intention of discouraging people from claiming relief.

Each union was governed by a Board of Guardians. These Guardians were responsible for the overall running of the workhouse and also for any ‘outdoor relief’, paid to people in their own homes. These board members were elected by rate payers in the various parishes in the union, and were members of the professional or merchant middle class. They had responsibility to keep poor relief costs to an absolute minimum, but went home themselves to a warm house and a good dinner. The day to day running of the workhouse was the responsibility of the workhouse master and matron, but the Bridgwater Board of Guardians met weekly and discussed costs in a very detailed manner. Reports of these meetings in the Bridgwater Mercury give an idea of the type of work carried out by George Crocker.

Accounts

In September 1886, the Clerk Paul Reed had presented a statement of statistical information to the Board of Guardians, comparing the expenditure in 1872 with expenditure in subsequent years. This statement was very detailed and it seems that the board turned with some relief to the condensed version produced and presented by George Crocker. This was grouped under five headings of expenditure:- out relief, in-maintenance, salaries, lunacy and county and police. An example of the effectiveness of the guardians in cutting costs was shown by the fact that in 1872, £10,531 was spent on ‘out door relief’, and this had gradually decreased until the total in 1886 was £6,684. (Bridgwater Mercury 22/09/1886).[i]

Regulations

The guardians had to ensure that people claiming relief were really entitled to it. In the meeting reported in the Bridgwater Mercury dated 24th November 1886, the Vice Chairman of the Board was grilling George Crocker about the financial circumstances of a particular claimant. A clerk who was being paid 23 shillings a week had claimed help with some medical costs, and the Vice Chairman thought that this person had sufficient income and should not receive help. He asked George Crocker a series of questions about the various circumstances in which this man might or might not be entitled to relief, for example if he was a member of the mutual society ‘The Oddfellows’. George answered his questions patiently and politely, although another member of the board knew the claimant and challenged the Vice Chairman. The regulations had to be quite detailed to deal with all circumstances, and part of George’s job was to know this sort of detail, and to investigate the personal circumstances of a claimant.

Ascertaining personal circumstances

The different poor law unions should only support people from the parishes that each union was responsible for. The Bridgwater Mercury of 19th September 1877 reported on ‘orders of removal’. The Clerk Mr Reed applied to the magistrates for an order of removal for a three year old child to be moved from the Bridgwater Workhouse to the Williton Workhouse. George Crocker stated that the child was the illegitimate child of a mother who gave birth in the Williton Workhouse. The mother had deserted her child and her whereabouts were now unknown. The order to remove the child was granted, as the costs of maintaining the child were the responsibility of the parish and union where he was born.

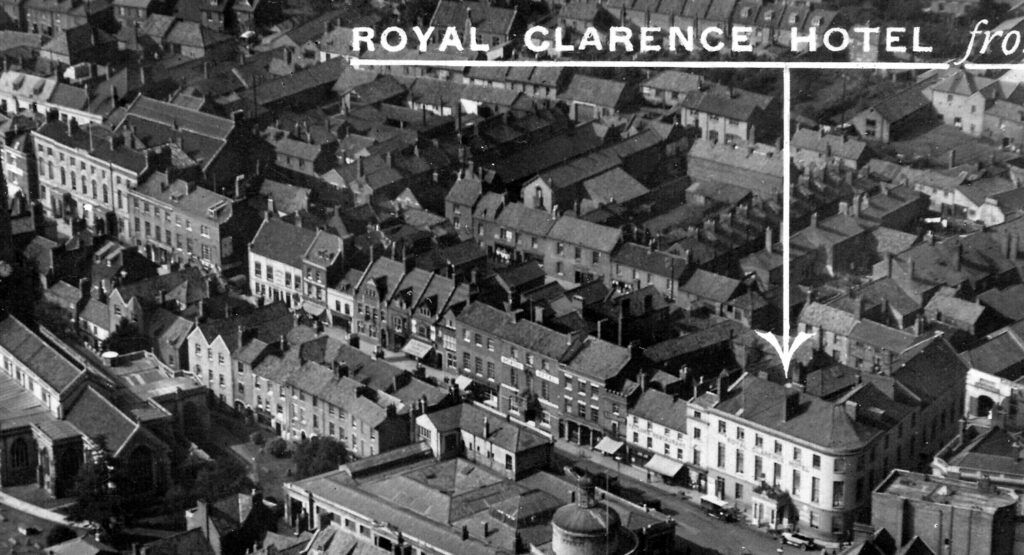

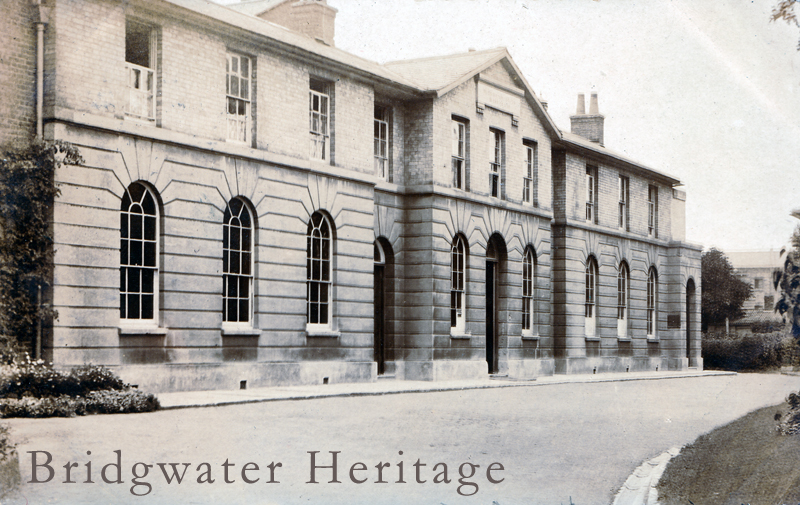

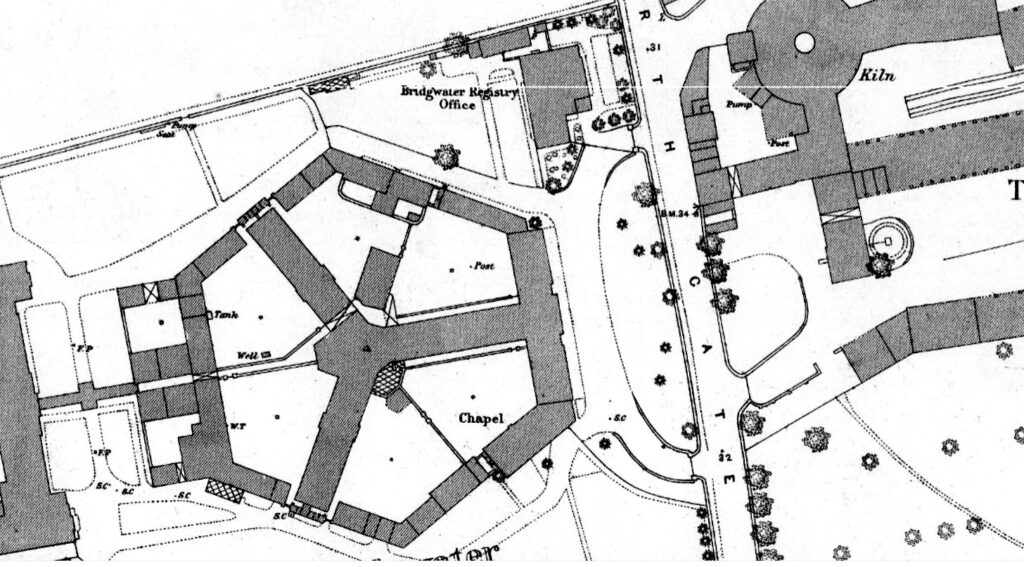

The 1881 census shows that George and his family were now living in North Gate, and George junior was at school. Their nephew was no longer with them, but Emily had the help of a live in servant, 17 year old Harriet Jones. Ten years later, George’s address is shown as the ‘Registry Office’, North Gate, so he had moved into the office building which was part of the Bridgwater Union complex. The Town Plan of 1888 shows that there were some gardens around this building, but it was close to the Workhouse and the railway line to the docks, and was opposite a large pottery kiln.

Registry Office and the registration of births, marriages and deaths.

Civil registration of births, marriages and deaths became a legal requirement under the Births and Deaths Registration Act of 1836. A new regulatory framework was not set up immediately, as the poor law unions had already been set up and those unions, based on groups of parishes, were a suitable size to become registration districts. Each registration district was in the charge of a superintendent registrar, and this job was always offered to the Clerk to the Board of Guardians. In Bridgwater, the Clerk to the Board of Guardians, Mr Paul O H Reed, was also the Superintendent Registrar and his deputy was George Crocker. The superintendent was the person in charge, but the actual work of registration was done by registrars who operated within a sub district. The superintendent and the registrars were not paid a salary, but were paid piecework, so their income depended on the number of births, marriages and deaths they registered, and any other statistics that they might be required to collect (such as cause of death during epidemics).

The 1836 Act had flaws, and another Act was passed in 1874 to remedy some of the problems. Registration was compulsory, but before 1874, the Registrar had the responsibility to collect information. After 1874 the onus was on the family members or other person applying for the registration.

The 1890s

The census of 1891 shows a happy time in the life of George Crocker and his family. George was living in the building where he worked, the Registry Office, together with his wife Emily and son George junior. The 23 year old George was working as an assistant to his father, and described his occupation as ‘accountant’, meaning that he dealt with financial information. Living with them were a 13 year old niece Olive Hobbs and a boarder, retired farmer Richard Tazewell. Emily probably had some domestic help on a daily basis. In Kelly's 1895 directory George was noted as School Attendance Officer, while his employer Paul Reed was the Clerk to the School Attendance Committee at the same time.

Unfortunately George junior became ill with tuberculosis and asthma, a very common illness in Victorian times. There was little medical treatment available, and young George died at home on the 5th of May 1895, aged 27. He was buried in Wembdon Road Cemetery, Dissenters plan 7 113.

Four years later, George’s wife Emily died, aged 53. She died at home at the Registry Office (Register House) on the 23rd of March 1899, the cause of death was heart failure and bronchitis. She was buried together with her only child, George junior.

George must have been lonely as one year later, he got married again, to Jane Ellen Brierley. Jane was 31 years younger than George. She worked as a sick nurse, so she may have met George while looking after his first wife, but she could also have been his housekeeper. The strict moral code of the time meant that it was safer for a single man to marry a housekeeper/carer, and prevent any damaging gossip.

In 1901 George and his new wife were still living in Bridgwater, but by 1911, George and Jane had retired to Burnham on Sea. George died on the 1st of March 1919, and he was buried in Wembdon Road Cemetery, together with his son George and first wife Emily, in Dissenters plan 7 113.

[i] The population in the Bridgwater Union in 1881 was 33,673, rateable value £232,600, acreage 85,645 – Kelly’s Directory of 1881.

References

Ancestry.co.uk:- Births, Marriages, Deaths, Census, Kelly’s Directory

Friends of Wembdon Road Cemetery

British Newspaper Archive – Bridgwater Mercury

Historic town plan: - https://www.somersetheritage.org.uk/#

British History Online, Victoria County History:-

https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/som/vol6/pp192-206

Civil Registration:-

https://media.nationalarchives.gov.uk/index.php/early-civil-registration/

Poor Law Board of Guardians:-

National Archives

https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/poverty-poor-laws/

https://www.workhouses.org.uk/Bridgwater/

https://bridgwater-tc.gov.uk/history/19th-century/the-bridgwater-workhouses/

Oddfellows Mutual Society:-