Josephine Clofullia Ghio nee Boisdechene 1829 – 1870

Josephine was raised to become a demure housewife on a Swiss farm, but she had a condition called hirsutism or hypertrichosis which causes excess hair growth. Because she had long facial hair, Josephine went on to be an international star as a ‘bearded lady’, travelling all over the world.

As a girl, Josephine was accepted in her childhood home, local area and boarding school, but as she began to travel further afield she met with intrusive curiosity and occasional abuse. She was married and gave birth to two children, yet lived under a constant cloud of suspicion and had to undergo more than one intimate medical examination to prove her femininity. In the deeply politically incorrect days of the nineteenth century, fairs often featured not only sad dancing bears but also ‘bearded ladies’. Unlike many of these which were fakes, Josephine was the real deal, a physically normal woman who happened to have excess body hair.

Early life[i]

Josephine was born between 1829 and 1831 in Versoix, near Geneva, Switzerland. She probably spoke French, but might also have spoken German. Her father Joseph was a soldier, her mother Francoise Masset was a farmer’s daughter. After his marriage, Joseph left the army and took up farming.

Both Josephine’s parents and her younger siblings had normal amounts of hair, but Josephine was born with a fine covering of downy hair. Doctors initially told her parents not to worry, but contrary to expectations, the fine down strengthened and grew into hair. However, doctors advised her parents not to cut or shave her beard as this might make it grow more strongly and become coarse.

When Josephine was eight she was sent to the same boarding school in Geneva which her mother had attended. She did well, particularly excelling in various forms of needlework. She stayed at this school until she was fourteen, but when her mother died Josephine was recalled from school and came home to look after her younger siblings and do the housekeeping. At this time her beard was about five inches in length and fair in colour, but it soon began to darken. Josephine was described as of middle height with a full figure and long dark brown hair.

Opposite her father’s house was a hotel, where travellers saw Josephine and became interested in her. Various theatre managers offered Josephine engagements but these were refused. Eventually in 1849 one of these made such a lucrative offer that Josephine’s father agreed. He put his other children into boarding schools and leased out his farm and house, so that he could travel with her. Josephine made her debut in Geneva where she had great success, then she travelled to Lyons, and from there around France. At the end of this contract, both Josephine and her father were enjoying travelling and they did not immediately take up a new one.

While they were staying in Troyes, Josephine met Fortuné Clofullia. Fortuné was an aspiring landscape painter and the son of Joyeux Clofullia, proprietor of a theatre in Troyes. Fortuné began to give Josephine lessons in watercolour painting and the young couple, both only nineteen, soon fell in love. They were married within three months. Josephine and Fortuné went together to Paris, where they met Louis Napoleon, later emperor of France, who gave her expensive gifts. After she styled her beard in the same fashion as his, Louis reputedly gave her a diamond which she wore in her beard.

Move to London

Josephine was with her husband Fortuné and his father Joyeux Clofullia on the 1851 census in Lambezellec in France. All three were described as Saltimbanques – travelling street or circus performers. They were also non-conformist in religion, and all three were described as Swiss[ii]. While in Paris they met several English people who suggested that Josephine come to London for the Great Exhibition in 1851. While in London, Josephine was examined by Dr Chowne of the Charing Cross Hospital, who was interested in her condition. He was satisfied that she was female. His statement, dated 22 Sept 1851, was subsequently displayed wherever Josephine was appearing. Dr Chowne also wrote an article about Josephine which was published in the Lancet 1 May 1852[iii].

Josephine and Fortuné had their first child, a girl called Jane Zelia Fortunne Clofullia on the 26th December 1851[iv]. Jane Zelia died in London Q4 1852. This little girl didn’t have excess body hair, but their next child, Albert, born in London Q1 1853, did have the same condition as his mother. Josephine obtained a statement from a London doctor to prove that she had given birth to Albert.

New York

The American showman Phineas Barnum heard about Josephine and offered her a very good payment to come to the USA and join his American Museum. This was a large exhibition displayed in a building in Manhattan, which contained a diverse mixture of attractions. These included living people such as ‘General Tom Thumb’ (Charles Sherwood Stratton), who was about 102 cm or 3 feet four inches tall, and the famously quarrelsome conjoined twins Chang and Eng Bunker. Live animals were kept in menageries, including miserable beluga whales in a tank in the basement. These poor creatures never lived long and had to be replaced quite often. Other attractions included scientific equipment, working models and dioramas, waxworks, paintings and educational lectures[v].

Josephine was soon involved in a court case in New York, which was thought to have been orchestrated by Barnum himself to generate publicity. A customer, William Charr, claimed that Josephine was a fake, just a man dressed up, and that Barnum had cheated him out of his entrance fee.

Witnesses for Josephine included her husband Fortuné Clofullia, who stated that she was his lawful wife, they had been married for three years and had two children, one still living. Her father declared that she was his daughter, now married to Clofullia and was the mother of two children. Barnum also produced affidavits by four American doctors who had examined Josephine and declared her to be female. Barnum won the case and got a lot of extra publicity for Josephine[vi].

Josephine toured in America with Barnum, then when her contract was finished she joined another show, Colonel Wood’s Museum. Her son Albert was first exhibited at the age of two and a half years in Havana, Cuba. Audiences gave him the nickname Esau as he had such long hair, and his stage name became ‘Young Esau the bearded boy’.

Josephine and Fortuné had married in haste while they were still both teenagers, and the marriage did not last. Towards the end of 1858, Josephine left Fortuné, according to a claim published in the New York Clipper on the 13th of November 1858. Fortuné declared that he would no longer be responsible for her debts. A further article published in the Evening Star 13 December 1858 claimed that they had made ten thousand dollars from Josephine’s shows, and discussed their custody arrangements saying that Fortuné had custody of Albert. Josephine herself said that her husband returned to ‘his native country’ in poor health, came back briefly to the USA but then returned home and died there[vii].

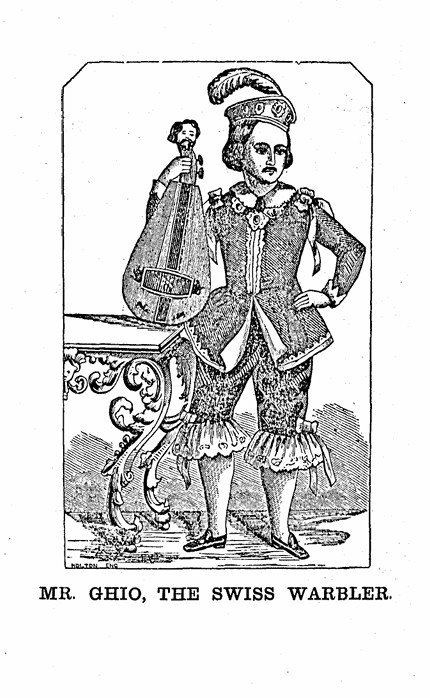

After the divorce, or Fortune’s death, Josephine married a fellow player from Colonel Wood’s organisation, a ‘Signor Joseph Ghio’, who worked as a Swiss Warbler, imitating bird and animal calls[viii]. The term ‘Swiss Warbler’ was then a description of the type of act, not an indication of nationality. Joseph Ghio was born in Genoa, Italy, but had lived in the U.S.A since he was a child. Josephine and Joseph married in St Louis.[ix]

Josephine, Joseph and Albert sailed from New York to San Francisco, arriving in early January 1862. After three months in San Francisco they toured around the principal places in California and Nevada. They then embarked on a voyage to Australia, arriving in Sydney on the 12th of February 1863, after a trip lasting 66 days.

Australia and New Zealand

Several Australian and New Zealand newspaper articles refer to their travelling show. Some of their appearances were for charity. A New Zealand paper, the Lyttelton Times of the 6th of June 1864 reports an admission price of two shillings and sixpence.

The Ghio family appeared at agricultural shows, hotels and other venues which were near where they were staying. They may have had a local manager, or organised much of it themselves. In June 1863 they appeared in Geelong together with another showman, magician and ventriloquist ‘Professor’ Thomas Rea. However, Rea wasn’t reliable and Ghio sued him for £9 in back pay, causing the end of their association.

Touring in the UK

By May 1865 Josephine, her son and Joseph Ghio had returned to the UK and were touring England without being attached to other acts. They had a ‘splendid pavilion’ which they erected in places like Twickenham, and advertised in the local papers. This pavilion may have been a gaily painted tent on a frame of wood which could be taken down easily and re-erected at the next town. They could have had a horse and cart to transport their pavilion, and any staging and furniture that went in it. Probably Joseph Ghio drove this himself, although they may have had a servant to help.

In advertisements, Josephine was always referred to as ‘the Swiss bearded lady’. This was to distinguish her from rivals[x]. A large part of Josephine’s attraction was that after she had appeared posing on a stage, she would come down and talk to members of the audience. She conversed very pleasantly in English and French, would answer freely any questions about her past, and allow people to touch her beard, which was reported to be soft and silky.

In the second half of 1867, they had a substantial contract to appear at the Fleur de Lys Music Hall in Sheffield (one of 6 music halls in the city). Ten other acts were on the bill, including comics, singers and dancers. After this there was a change and Signor Ghio was no longer performing with Josephine, he had probably died (her newspaper death notice refers to her two husbands). This would have been a difficult time for Josephine. As well as her grief, she had to continue to work and needed some help to set up and pack away her booth/pavilion, as well as provide a deterrent to over-familiar people intent on pulling her beard. Albert was still only fourteen and would not be strong enough.

Josephine and Albert travelled together around the big fairs, appearing in their own booth. They attended large fairs in Bolton and Leicester, and probably many smaller ones. In Shrewsbury, Josephine and Albert were again appearing on their own in their splendid pavilion, she charged one shilling admission, although now the entrance price to see Albert separately (stage name Esau) was two pence. According to her own advertisements, Josephine was planning to go to the U.S.A in the near future so she was saving up.

West Country Fairs

Josephine and Albert were still in England in April 1870, when they exhibited at the Easter Fair in Exeter. This may be the same fair which moved to St Matthew’s Field in Bridgwater in late September that same year. In Exeter Josephine was one of many attractions, including steam powered roundabouts with ‘hobbies’ or wooden horses, a working model of a ribbon factory and a Temple of Artemis. The whistles produced by these steam powered machines added considerably to the already deafening noise coming from the fair. There also automaton birds which whistled and hummed. Weight’s Theatre was present and presented several different performances. A zoological menagerie contained a lion maned monkey among other animals, there was also an ‘Egyptian Mummy’ posing on a pedestal, and a pig with extra legs. As usual there were conjurers, jugglers, strong men, boxing booths, shooting galleries, nut and sweet stalls. Albert would be working the crowd outside their booth, encouraging people to come in and see Josephine. Inside, Josephine remained calm and dignified, always well dressed and polite.

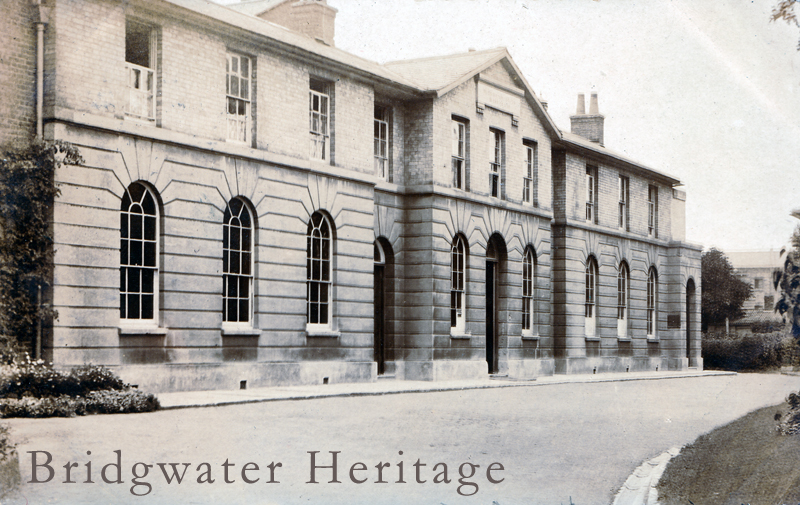

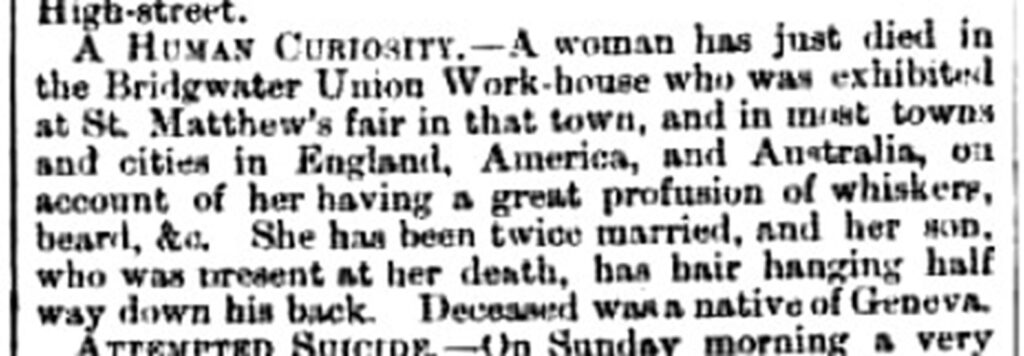

After the St Matthew’s fair, Josephine fell ill and had to stay in Bridgwater, while the rest of the troupe moved on. Her son Albert stayed with her and was present at her death on the 1st of November 1870, in the Bridgwater Union Infirmary. Albert was described as having hair hanging halfway down his back. (West Somerset Free Press 5th Nov 1870). Her cause of death was ‘low fever’, which simply means that no one knew the cause of her fever. It wasn’t typhus, which causes a high fever, in the 19th century doctors would be able to diagnose that, as well as other common infections such as cholera, or any that caused a rash or abscess. This unknown infection may have resulted in sepsis, which caused her death.

Her death and burial were registered under the name Josephine Cloffullia, and she was described as ‘the widow of Joseph Cloffullia, a showman’. Albert, then aged 17, stayed with his mother, and he had retained his birth surname. Albert probably gave the workhouse staff information that his own surname was Clofullia, and that his mother Josephine was a widow, as her husband Joseph had died.

After a career of travelling the world, meeting many people and living among the sawdust and spangles of travelling shows, Josephine died in poverty in the workhouse, and was buried in a pauper’s grave.

Josephine didn’t have a great deal of choice in her life. She couldn’t help her condition at the time, and as a woman without independent means she spent most of her life being told what to do by men, who probably used her earnings. Initially her father directed her life, and then her two husbands. But being born in the early part of the nineteenth century, this would have seemed normal to her.

The men around her would have protected her as much as possible, but she must still have faced a good deal of prejudice. Newspaper reports of her appearances often either dismissed her as an obvious fake, or described her as a monstrosity. It is difficult to know how happy Josephine had been. Someone who had spoken to her described the experience, and commented that she appeared happy and was quite proud of her beard. When she went out and wasn’t working she often wore a handkerchief over the bottom of her face, but it seemed this was because she tired of the constant attention, not because she was ashamed. Josephine was a cultured and intelligent woman who promoted the biography written about her to aid understanding. She worked quietly to counteract prejudice by mingling with her audience, speaking gently but freely and allowing her beard to be touched. Those people then came away with a very favourable impression. Josephine has left us the story of a woman who was different, but who made a success of her life. She was a loyal wife and mother, a reliable performer and she showed good judgement and respect for those around her.

Clare Spicer and Jill Trethewey 17/04/2025

Postscript: How we found Josephine in the Cemetery

The Friends honorary archivist, Michelle Craig, while looking for something else in the online newspaper archive, accidentally came across this story in the West Somerset Free Press for 5 November 1870:

Annoyingly, this report fails to mention the name of this poor woman. However, a look through the Workhouse Register of Deaths reveals her:

29 October 1870: Josaphine Cloffillia of Bridgwater, aged 42, buried in the Bridgwater Cemetery

Then we can find her in the burial register of the cemetery:

2 November 1870 JOSEPHINE CLUFFULIA of Union House [the workhouse] aged 42 years, buried Officiating Minister Reverend W. G. Fitzgerald.

Just a cursory look on google revealed this to be Josephine Clofullia. Much of her story had quite recently been highlighted in recent years by the historian Sean Trainor.

Josephine, the woman who had performed for kings and emperors and had travelled the world, ended buried in a communal plot, surrounded on all sides, above, below, front, back, both sides, by fellow paupers.

We were then able to acquire her death certificate. The certificate records that Josephine died in the company of another inmate of the Workhouse, an elderly widow called Mary White, who could only sign the witness statement with a feeble cross.

Mary was a Bristolian, born in 1801, and the widow of a Moses White, who died sometime in the 1850s. After his death Mary spent the rest of her life in the Bridgwater Workhouse. She's mentioned there in 1861 and 1871, described as a domestic servant. She died there on 25 January 1875, and was also buried in the Paupers' section of the cemetery, in the same ground as Josephine.

MKP 2020

[i] Information for Josephine’s early life was drawn from a contemporary biography – ‘Life of the celebrated bearded lady’, published 1855 New York. NB this includes a line drawing of Josephine with her two children, but the first, a girl, died before the second, Albert was born. https://archive.org/details/lifeofcelebrated01unse/page/n9/mode/2up

[ii] 1851 French census available on Ancestry.co.uk.

[iii] W.D.Chowne M.D. REMARKABLE CASE OF HIRSUTE GROWTH IN A FEMALE; WITH OBSERVATIONS ON CERTAIN ORGANIC STRUCTURES AND THEIR PHYSIOLOGICAL INFLUENCES. Published in The Lancet Volume 59, Issue 1496 p421-422 May 01, 1852

[iv] Jane Zelia’s birth record has not yet been found, but her death record in London is on record.

[v] Barnum’s playbill, image published in Gleason’s Pictorial Drawing Room Companion:-

https://www.google.com.au/books/edition/Gleason_s_Pictorial_Drawing_room_Compani/2MNto188EskC?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=Fortune+Clofullia&pg=RA1-PA268&printsec=frontcover

[vi] Taunton Courier and Western Advertiser 20 July 1853.

[vii] There is a record of an F. Clofullia, artist, arriving in the UK from France in 1859 (Ancestry HO 3 Home Office Aliens Act 1836 Returns and papers. There is a possible death record for a Fortune Clofullia in 1877 in France.

[viii] No records of divorce from Fortune Clofullia or marriage to Joseph Ghio have yet found.

[ix] Information from the biography, apparently updated by Josephine herself and in the State Library of Victoria – ‘Biography of the celebrated Swiss bearded lady, Madame Ghio, and her son Esau’. Published Sydney, Caxton General Printing Office 1863. https://find.slv.vic.gov.au/discovery/fulldisplay/alma9912739403607636/61SLV_INST:SLV

https://viewer.slv.vic.gov.au/?entity=IE4173492&file=FL17060180&mode=browse

[x] There were several bearded ladies in the USA, a contemporary one was Julia Pastrana, who also had hypertrichosis, but was referred to as ‘the bear woman’.