Anglican Section H, Memorial 19/509

by Jillian Trethewey, Hilary Southall and Clare Spicer 28/1/2021

William Dyment was a Bridgwater man who for many years was a cheese factor with the firm of Messrs Thompson and Collins, wholesale cheese factors, St Mary Street.

William Dyment was baptised on the 8th April 1836 at the parish church at Charlinch, Somerset, though his parents were living just over the parish border in the hamlet of Four Forks, Spaxton. His father Isaac Dyment was a carpenter who had married Eliza Waterman in 1835. The villages of Charlinch and Spaxton were about five miles west of Bridgwater.

In 1841 at the time of the census, Isaac and Eliza Dyment, their five year old son William and Eliza’s mother Mrs Elizabeth Waterman, were in the same household at Four Forks, Spaxton. Isaac was a carpenter still but within a couple of years he had a change of career. By the time their next child Emma was born in 1843, they had moved to St Mary Street, Bridgwater, where Isaac was the innkeeper of the “White Horse.” [1] Two more children were born in Bridgwater, Elizabeth in 1845 and George in 1847. Unfortunately Emma died in 1847 and is buried in the churchyard at Spaxton.

Sadly, Isaac Dyment died aged 36, struck down when the third cholera pandemic reached Bridgwater in 1849. “Asiatic cholera” could kill a healthy adult within hours or days and about two hundred men, women and children died in the town. The White Horse inn wasn’t doing well either, not helped by the fear of cholera. Isaac’s two main creditors were John Northcott, maltster, of Nether Stowey and James Blake, spirit merchant of Langport, and on the 18th October 1849, they seized his assets. [2] The Dyment family were living in High Street when he died. Isaac was buried on the 24th October 1849 in the churchyard at Chilton Trinity, two miles north of Bridgwater, instead of at St Mary’s, by special arrangement due to the epidemic.

So at the age of thirteen, William had become the man of the house. His mother Eliza showed strength of character and determination in keeping her family together. In 1851 they were living at Back Quay, Bridgwater (now Binford Place), and Eliza, aged 42, was working as a tailoress. With her were William, fifteen; Elizabeth, five; and George, three; plus a little nephew, Charles Waterman. The widowed Eliza married a widower John S. Vickery, an auctioneer, in 1854, and went to live with him in Swansea, Wales.

William must have been a bright boy who had done well at school, because in 1851 he was already working as a clerk. For most of the nineteenth century, many young men were employed as clerks in business and government, as the only way to record invoices and receipts and other transactions was by hand in ledgers. Similarly if a businessman or government official wanted a duplicate of a document, it had to be copied by hand. This was before typewriters and before women worked outside the home. The clerks came to work in hat, coat, suit and tie and sat at desks where they were expected to work long hours for low wages. Promotion was by length of service often rather than according to ability. Any tardiness, mischief or disrespect would usually result in dismissal without a reference. Despite all this, William Dyment worked for many years for Thompson and Collins, wholesale cheese merchants, and rose through the ranks.

On the 13th May 1856, William, now an accountant, married Jane Gwyther, a bonnet-maker, at Bedminster, near Bristol. They married by special licence, for more privacy. William put his age up a year to 21 and Jane put hers down to 24. Jane was the daughter of George Gwyther, a Welshman, and his wife Emma, who had lived in Bridgwater all their married life. Captain Gwyther, a master mariner, had been in coastal shipping for many years. By 1856, Captain Gwyther owned a home in Friarn Street, Bridgwater. [3] So in 1861, Captain Gwyther, his wife and son were living in Friarn Street but they had also made room for the young Dyment family and William’s younger brother George. William Dyment was again an accountant, his wife Jane was a straw-bonnet maker and they now had two children, George William aged two years and Eliza Jane aged two months. Jane was born in 1820 and was now forty years old, but discreetly took a few years off her age for the census.

William had a wife and family, a steady job and a secure home, even if living with his in-laws. So how did William come to be involved in an investigation into political corruption? To what extent William wanted to work for the Liberal Party and how much he felt obliged to do as his employer wished, remains unknown. There is no doubt that Thomas Collins, cheese factor and later Mayor of Bridgwater, was a Liberal Party stalwart. [4]

The Bridgwater Election Commission of 1869 had the task of investigating allegations of corruption in recent Bridgwater elections. It must have been an anxious time for William Dyment as he stood in front of the Commission in the Bridgwater Town Hall.

The London Standard reported the questions the Commissioners put to William Dyment and the answers he gave, beginning with his recollection of the 1868 election:

William Dyment, clerk to Mr Collins, cheese factor, had attended to the registration, and was on the executive committee for forming a Liberal Working Men’s Association. A week before the election, Mr Lovibond came to him to assist to make out the list of doubtful voters. Understood by this was meant the men who would have to be bribed. The town was divided into districts for this purpose. He consented at first, but on reflection declined to have anything to do with it. At first it was understood the Tories did not mean to spend money, but afterwards it was found they were polling doubtful votes, and witness told Mr Lovibond something must be done. Up to twelve o’clock there was nothing decided about it, and the men were hanging about. Told Mr Lovibond that although they were then in a minority, the election could be won, and told Mr Lovibond that out of every five unpolled voters the Tories dared not bribe them. The witness afterwards pressed a voter named French to poll. [5] He would not poll without money and by Mr Cook’s direction he offered him £10, but he refused to poll without the money. His wife just then came in and he sent her for £10. His employers expressed their surprise and sorrow at what he had done. He had never got the £10 back again. He deserved to lose it. He had no claim on anyone but Mr Cook. He next gave evidence as to the second election of 1866. He had gone to London to fetch a voter, but the voter was too ill to come. At the first election in 1866 he went to Taunton and fetched a draper named Bottomley to poll. He took him to the Railway Hotel and told the landlord he would pay the bill. Bottomley had been declaiming on the journey against bribery, but said he thought voters ought to be paid their expenses. When at Bridgwater he hesitated about polling and wanted £10 for expenses, but witness gave him two guineas. He said he would rather have nothing than that, and accordingly witness had the money back again. [6] He also paid a voter named Burrington £10 for his vote. He also bribed the same voter in 1859 with £10. He got the money from Bussell.”[7]

The Bridgwater Election Commission sat from the 23rd August to 16th October 1869 and questioned over five hundred Bridgwater men about the recent elections. [8] There had been allegations of political corruption in Bridgwater for decades, but in 1865, a successful candidate was shown to have paid for votes. In the nineteenth century, generally only men who owned land had the right to vote. The ordinary working man and all women were thus excluded. The Second Reform Act of 1867 added men who were ratepayers, though not owners, to the electoral roll if they were renting a property above a set value. Voting was not compulsory and nor was it a secret ballot. In a town the size of Bridgwater, there may have been only around six hundred men who actually voted. This made it feasible for both the Tories and the Liberals to identify the swinging voters and then bribe them. This was of course illegal, but at least two men told the Commission how it was done.

Henry C. Bussell, the landlord of The Anchor, was a Liberal supporter. He said that at the last election, he tried to persuade the voters to go to the poll as he was convinced the Liberals could win. “About eleven o’clock the Conservatives were one hundred ahead and he went to the Globe and saw the Liberal solicitors and in answer to them he said that £4,000 would be required to win the election. The lawyers retired for some time and then returned to him, and Andrew Allan and others said they had decided not to spend any money as there was no chance of winning. With this understanding he went about the town, advising the electors to poll. At three o’clock the Liberals were only eight behind and he again went to the Globe and saw Mr Reed or Mr Cook the lawyers, who told him to get all the money he could as there would be some money. He was shown into a darkened room and saw a tall and dark man – a stranger – who gave him £125 in £25 packages. He then returned to his house and bribed seventeen persons and he also gave £20 to a man named Fisher, to bribe two other persons. ………. Witness paid fourteen men £10 each using £15 of his own money. A fresh lot of voters came and he then went to the Globe for more money. The result was he was again introduced to the stranger who asked him how he was getting on. He replied “we shall win” and then received sixty sovereigns more.” [9] Each sovereign was worth one pound sterling.

Andrew Allan, glass and china merchant of Bridgwater, admitted to bribing over thirty voters and supplied names and a detailed account of his involvement. He insisted that he and Bussell used their own money and that he knew nothing of a mysterious stranger. Allan went on to describe another occasion. “Mr Brogden introduced him to another gentleman, a stranger, whom he did not name. He was dressed in dark clothes and looked like a Wesleyan preacher or a waiter. He was a man of about fifty years. The stranger opened a bag and gave him £1,400 in sovereigns. It was more than he could carry at one time and he took it home to his house at three different times.” Allan then named another twenty or so men who had been given money, usually £10 per vote, and William Dyment had obtained one vote in this way. [10] Others were reimbursed for entertainment expenses, such as drinks on polling day to incapacitate voters who could resist a bribe but not a beer. [11]

The proceedings of the Commission were widely reported in the press. The outcome was that the town of Bridgwater was disenfranchised and lost its seats in Parliament. The corruption was so entrenched that there was no other way. The mysterious stranger was never identified. [12]

After 1869, life went back to normal for William Dyment and if he was mentioned in the national press again it was as a judge of cheeses at county shows. Somerset is renowned for its dairy industry and for its cheddar cheeses. Bridgwater had a regular cheese market as early as 1700. The town's markets were by the 1790s the 'most considerable' in the county for corn, horned cattle, sheep, pigs, and cheese. [13] Inland from Bridgwater is the region known as the Somerset Levels. In winter the moors were too water-logged for crops but the lush pastures from spring to autumn were ideal for dairy farming. The traditional use of the milk was for cheese-making and Bridgwater Cheddar Cheese was especially prized for its flavour. [14] The other kind of cheese made by the moorland farmers was Caerphilly cheese, but this was perishable, whereas Cheddar could be kept for much longer even without refrigeration. The traditional Cheddar cheese was coloured on the outside with reddle, or redding, a red powder quarried in the Mendip Hills.

In William Dyment’s time, new scientific and technological thinking was being applied to food production, including cheese-making. Joseph Harding (1805-1876) was a Somerset man who has been called “the father of Cheddar cheese.” He taught dairy farmers and cheese-makers that temperature control and strict hygiene were essential in the production of cheese. Harding described good cheese as "close and firm in texture, yet mellow in character or quality; it is rich with a tendency to melt in the mouth, the flavour full and fine, approaching that of a hazelnut". [15]

Another local cheese-making expert, Edith J. Cannon, wrote in 1892, that despite attention to the level of acidity throughout the process, the variations in the quality of milk from cows feeding on different pastures and the effects of temperature in the ripening of cheese, “defects in cheese-making would arise, now and again, in dairies presided over by the most skilled and careful makers.” She was convinced that the reason for an excellent cheese one day and an inferior one the next, when nothing else had changed, was due to bacteria, especially from contamination of the milk before it reached the dairy. Dirty hands and dirty cows were the problem and cheese-makers had to understand that bacteria, although unseen, were fighting either for or against them. [16]

As a travelling salesman promoting the cheeses of Thompson and Collins, William would have needed to be familiar with all aspects of cheddar cheeses, including the benefits of the latest scientific advances. As William became more experienced and was promoted within the firm, he would have had added duties including assessing new suppliers and their cheeses. Did it pass the taste test? Was their product good and reliable? Were they using modern cheese-making methods? Was the quality in keeping with the price?

William’s loyalty to the firm of Thompson and Collins was eventually rewarded and sometime after Collins’ death in January 1882, William became a partner. [17] In 1883 there were five cheese factors in Bridgwater and Highbridge and only Thompson and Collins had an office in both towns. Their Bridgwater premises were in St Mary Street. [18] Imagine their warehouse with rows of great wheels of cheddar cheese stacked several feet high.

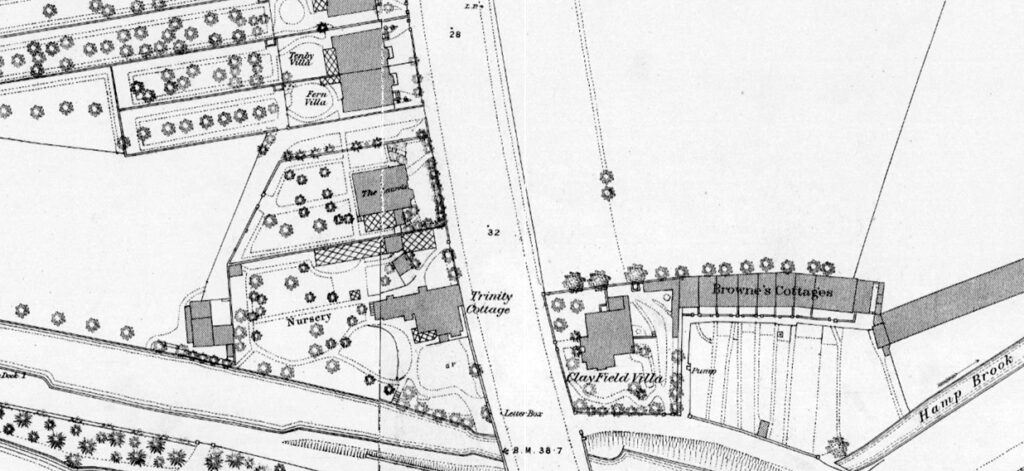

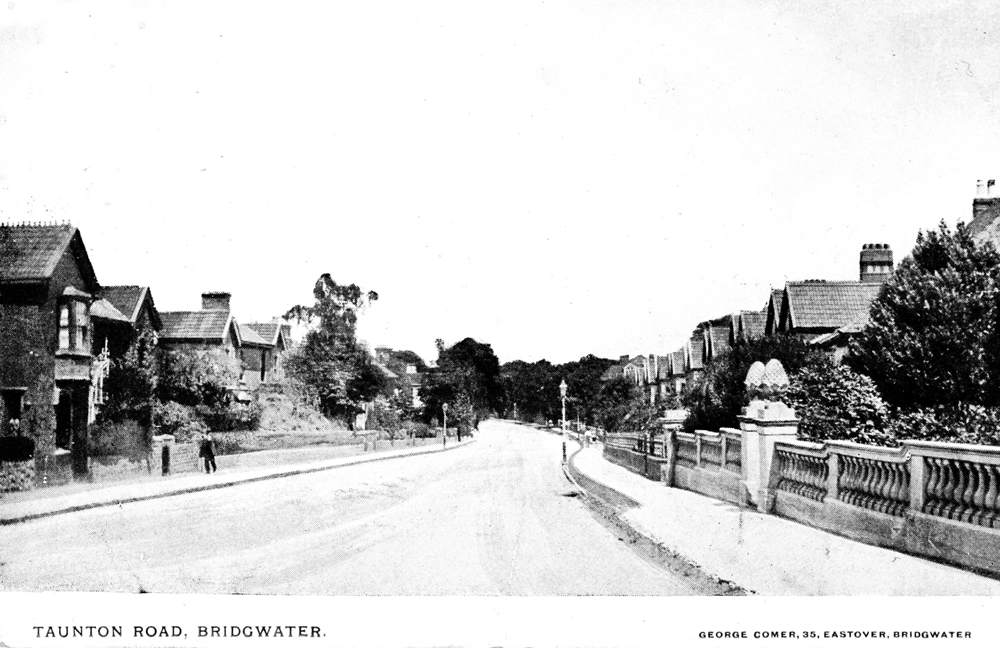

In 1871 and 1881, William and Jane and their two children were living in Taunton Rd and William was a commercial clerk and traveller. In 1891 and 1901, they were living in Tenby Villa, Taunton Rd, and William’s son George was a clerk to a cheese factor, almost certainly at his father’s firm.

William died aged 71 in July 1907, as reported in the Western Daily Press: “The death occurred, at his residence, Taunton Road, of Mr William Dyment, his 71st year. The deceased gentleman, who for many years had been a member of the firm of Messrs Thompson and Collins, wholesale cheese factors, of Bridgwater, was well-known in agricultural circles. He was a frequent judge at the Bath and West and Somerset County Agricultural Shows and was a recognised authority on all matters related to cheese.” [19]

At the monthly meeting of the Bridgwater town council: “Reference was made to the death of Mr. William Dyment, an old townsman, and for many years a member of the Free Library Committee, and a letter of sympathy was directed to be forwarded to the family. [20]

Mrs Jane Dyment died on the 15th August 1909 aged about 89 and is buried with her husband at Wembdon Road Cemetery.

In 1911 George W. Dyment and his sister Eliza Jane were both retired and still living in the family home at 26 Taunton Rd. Neither had married. George died in April 1937.

The death occurred at the Rose Bower Nursing Home Thursday night of Mr. George W. Dyment, of 26 Taunton-road. Mr Dyment, who was 78, was formerly in the cheese factor's business Messrs. Thompson & Collins, St. Mary-street, and in his younger days was interested in the Bridgwater Dramatic Club, of which he was one of the earliest members. He was also formerly a keen tennis player. The remains were cremated at Bristol on Monday and in the afternoon the ashes were interred in the Wembdon Road Cemetery, where a short service was conducted by the Vicar of St Mary’s (Preb. E. H. Hughes-Davies.) Among those attending were Mr D. G. Denman and Miss Denman, Mr Dyment (cousin, Bristol), Mr Harold Davis, Mrs Whitson, Miss Stuckey and Mr W. J. Williams (representing Messrs Reed and Reed.) [21]

By 1939 Eliza Jane Dyment was also a resident of the Rose Bower Nursing Home at Bridgwater. She was partially incapacitated. Eliza died on the 17th July 1940.

[1] Pigot’s 1842 Directory for Bridgwater.

[2] London Gazette Nov 1849 – Notice of an Indenture of 18th Oct 1849.

[3] 1846 electoral roll for the Borough of Bridgwater.

[4] Weston Mercury 21 Jan 1882 – obituary of Alderman Thomas Collins, Mayor of Bridgwater and cheese factor.

[5] The Western Daily Press. Tues 14 Sept 1869, added that the man French was the landlord of the Rose and Crown and that Mr Cook was a solicitor.

[6] The Western Daily Press. Tues 14 Sept 1869, added that Bottomley, the draper from Taunton, was formerly a schoolmaster in Bridgwater.

[7] The London Standard, Tues, 14 Sept 1869

[8] Lawrence J.F. revised by Lawrence J.C. A History of Bridgwater. Phillimore & Co. 2005. Page 162.

[9] The Western Times, Exeter, Fri 3 Sept 1869.

[10] West Somerset Free Press, 4 Sept 1869.

[11] Evans, Roger. The Book of Bridgwater. Halsgrove 2006.

[12] Squibb’s History of Bridgwater. Pages 87-88.

[13] A History of the County of Somerset: Volume 6, Andersfield, Cannington, and North Petherton Hundreds (Bridgwater and Neighbouring Parishes). Originally published by Victoria County History, London, 1992.

[14] The Story of Cheese-making in Britain. V.E. Cheke. 1959.

[15] Hawkins, Desmond. Avalon and Sedgemoor. Alan Sutton. Gloucester. 1982. Page 123.

[16] Cannon, Edith J. The Manufacture of Cheddar Cheese. Reprinted from the Journal of the Bath and West and Southern Counties Society. Bath 1892.

[17] London Gazette 6 Dec 1895

[18] Kelly’s Directory of Somerset, 1883.

[19] 16 July 1907 - Western Daily Press - Bristol, England

[20] 25 July 1907 - Wells Journal - Wells, Somerset, England

[21] 17 April 1937 - Taunton Courier, and Western Advertiser - Taunton, Somerset, England