Eliza was one of the oldest people to be buried in the Wembdon Road Cemetery. When she was a girl sailing ships crowded the River Parrett, but she lived to see planes flying over Bridgwater. Eliza lived most of her life in Bridgwater and was still living alone in Angel Crescent in her nineties.

Mrs Emma Day (1788-1855) who also has a biography on this website, was Eliza’s husband’s grandmother.

The Baker Family

Eliza had humble beginnings and the official records of her birth and her parents are sketchy and ambiguous, as Baker was a very common surname. Uriah and Hannah Baker were most probably her parents, but if new information comes to light this may need review.

Eliza’s ancestors on both sides of her family had worked on the land in west Somerset for a hundred years or more. Her father was Uriah Baker (1821-1886), a farm labourer who was born in Othery, near Bridgwater, to Joseph and Rosanna Baker. In the winter of 1835, when Uriah was only fourteen, he and his elder brother James were caught stealing turnips. They both had a previous conviction for stealing food and this time they were sentenced to 14 days in Wilton Gaol, near Taunton. These were the hungry years of the Corn Laws, when the price of bread was very high, but wages did not keep pace. Surprisingly the brothers had attended either a charity school or a Sunday School in Bridgwater until five years previously.

For the next ten years, Uriah stayed out of court but perhaps not out of trouble. Hannah Every or Avery (1820-1888) was born in North Petherton, just across the River Parrett from Othery. In 1843 she gave birth to a son, Charles, who was registered as Charles Every, but was raised as one of Uriah’s children. Hannah and Uriah were married in 1845. In the December of the same year, Uriah was before a judge again. He was convicted of stealing a sovereign, a £1 gold coin, and was sentenced to four months hard labour in Wilton Gaol. Hannah’s second child, Ann, was born at Othery while Uriah was in prison.

Uriah returned home to his family and he and Hannah had a daughter Eliza born in 1848. They moved to Barclay Street, Bridgwater, where Eliza died in 1849. Eliza Ann Baker was born at the Mount, Bridgwater, on 3 September 1850. They soon moved again. Mary Jane was born in the village of West Monkton in 1854 followed by Henry in 1855, who died in infancy, and Louisa in 1856. Labourers generally had to move around to find work, but Uriah also had the stigma of having done time. Poor people were unfairly equated with the so-called “criminal class” anyway. Uriah and Hannah would naturally want a fresh start. They moved to Bedminster, near Bristol, where Uriah and his son Charles worked as gardener’s labourers.

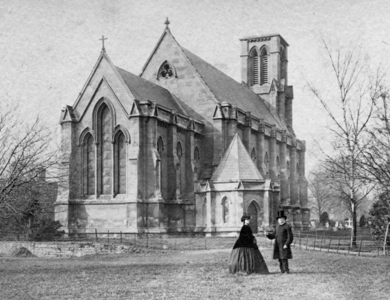

Meanwhile, Ann and Eliza had both returned to Bridgwater, likely to work as housemaids. They next appear in the official records at their double wedding on 18 November 1866 at St John’s Parish Church, Eastover, Bridgwater. Ann married fisherman Alfred Counsell and Eliza married James Day, a coach trimmer. Eliza was only sixteen, but she put her age up by two years. The vicar recorded that their father was John Baker, labourer. Both girls could sign the marriage register and so presumably could read, but neither corrected the error. Did they just not notice? They may have been afraid of the vicar finding out about Uriah’s convictions and that Eliza was a minor. In both register entries the witnesses were friends, not family.

The Day Family

James Day was born in Bridgwater in 1845. His father James Day (1821-1883) was a letter carrier or postman and his grandfather was a shoemaker of High Street, Bridgwater. James lost his mother when he was nine and he and his sister and brothers were sent to live with various family members until their father remarried the following year. James initially trained as a saddler and harness maker, but found that his skills were needed in coach-making. Traditionally coaches were horse-drawn, but coach-makers were also employed to build and maintain the carriages of the Bristol and Exeter Railway and later the Great Western Railway (GWR) at Bridgwater. Carpenters and joiners built the wooden body of the coach which sat on a steel frame and wheels. A coach trimmer upholstered the seats and fitted leather panels to the walls and doors where required. Some handles and overhead hand grips may also have been made of leather. Then there were the ongoing repairs of the upholstery of railway carriage seats in particular.

Eliza and James

Eliza’s first child, William James, was born in July 1869 when they were living in Back Street, Bridgwater (now Clare Street). Two years later in the census, he was confusingly listed twice, with his parents in Bridgwater and again with his grandparents Uriah and Hannah. Eliza’s happiness as a wife and mother was tempered by the difficulties her sister Ann was facing. They were eighteen miles apart but, by rail, close enough to visit each other when needed. Ann certainly needed support in the early years of her marriage.

Ann and Alfred lived at Weston-Super-Mare, north of Bridgwater on the coast. In the summer of 1867, the yacht Wanderer, a new zinc boat loaded with iron ballast, capsized in a stiff breeze and the two young men sailing it were feared drowned. Alfred joined the search and a week later he found and helped bring one of the bodies to shore. A subscription was raised by the townsfolk to reward Alfred and his friends. This was his public image: a well-liked, competent boatman. It was different at home. Eventually Ann was badly injured and Alfred was arrested and held in custody. The following report was published in the Weston-Super-Mare Gazette in July 1868.

“At the Weston police court, on Wednesday, before Messrs R. A. Kinglake and J. Cox, a boatman named Alfred Counsell was brought up, in custody, charged with assaulting his wife. Mr Solomon defended. From the evidence it appeared that on Saturday evening last, prisoner came home to his meals, when his wife got up to put a cat out of doors. Prisoner then remarked that he would put her out and when replying that he could do that if he thought proper, he seized a knife that was lying on the table and stabbed her with it over the eye. In reply to the bench, complainant said that she had only been married 18 months, and that ever since that time he had continually ill-used her, so much that her body was always covered with bruises. Mr. Solomon pleaded that the prisoner and his wife were having their meals together, when some altercation arose, and on the wife making an improper remark, the prisoner took up his plate, with knife and fork, and threw it at her. He further urged that under the old common law, a man was allowed to moderately correct his wife. Mr. Kinglake said the bench did not consider stabbing a moderate correction and inflicted a fine of £2, including costs, or in default, 14 days hard labour.”

Today it seems so wrong that a magistrate would think a fine of £2 adequate for a proven physical assault against any woman. Domestic violence was then called wife-beating, but for the deplorable reason given by Mr Solomon, was not usually prosecuted in court unless it had escalated to be a breach of the peace, or resulted in a serious injury or death. Since it happened on a Saturday evening, it is very likely that Alfred had been at the pub drinking. The Temperance Movement was in full swing because so many men drank to excess, beat their wives and children, were involved in accidents, lost their jobs and harmed themselves or others, but the community just accepted this. There was no government assistance for Ann. The disclosure in open court meant Alfred could not hide what he had done and those who cared for Ann, including Eliza, could now offer practical help and emotional support. This was neither the first nor the last time that Alfred was in court, usually for assaulting other men. Ann and Alfred remained living in the same house, but they did not have children.

Meanwhile, Eliza and James had moved to 1 Roberts Court, Eastover, and Uriah and Hannah Baker had moved to North Petherton, probably to Somerset Bridge or Crossway, just south of Bridgwater. Uriah was a fence-keeper working for the Bristol and Exeter Railway, which owned the Bridgwater to Taunton Canal. He maintained the fences and hedges along the canal.

Eliza was soon very busy with six children under twelve while James continued to work as a coach trimmer. Lavinia was born in 1871, Frank in early 1874, Eliza Ann later in 1874, Frederick in 1877, Florence in 1878 and Emily in 1880. Frank is thought to have died in infancy. James and Eliza were not regular churchgoers when the children were small, at least not for baptisms or not at the parish church. The younger four were baptised at St Mary’s when Emily was a baby.

By 1881, James and Eliza and their children were living in Angel Crescent, close to St Mary’s school. As a skilled tradesman, James had stable, year-round employment. This was a great advantage when so many working men were laid off over winter. The street number changed from “23” to “7”, but Angel Crescent was Eliza’s home for the rest of her life. Rosanna, named after her great-grandmother but called Hanny, was born in 1883, Harry in 1885 and Wilfred in 1888. Eliza’s parents were living at 73 Barclay Street in their final years, close to both their daughters Eliza and Mary Jane. Uriah died in 1886 and Hannah in 1888. They had remained close to their daughters and both Eliza’s and Mary Jane’s elder sons had stayed with Uriah and Hannah at various times.

It was perhaps a greater shock for Eliza when Mary Jane died in March 1891, in her mid-thirties. Mary Jane had married William Uriah Laver, a mariner in the merchant service, and was living in Chandos Street, Bridgwater, near the River Parrett. They had five sons and the youngest was only three when Mary Jane died of chronic metritis. This was a bacterial infection of the womb, which in the 19th century was usually a complication of childbirth or a miscarriage. It was a painful condition that would now be treated with antibiotics. If they survived the acute infection, some women would recover, but others like Mary Jane were left with pelvic pain, intermittent fever and other symptoms for months or even years. Their eldest sister, Ann Counsell, died in 1899.

Eliza’s children were growing up and leaving home. William went to sea and became a marine engineer. William’s offspring were Eliza’s first grandchildren, but they lived in Cornwall. Lavinia, the younger Eliza Ann and Florrie all married in the 1890s. These were all happy events, but in October 1897, Frederick Day was admitted to the Cotford County Lunatic Asylum at Bishops Lydeard. Whether it was a mental illness or another condition such as epilepsy, we don’t know, but it must have been a terrible time for Frederick, Eliza and James and all the family. Visitors to inmates in Cotford were permitted, but not expected. As his mother, Eliza would never have forgotten him and maybe she was able to make the journey by train to Taunton and then by horse and carriage.

It was not until the beginning of the new century that Eliza and James had grandchildren living nearby. Lavinia and her husband John Weekes Hawkins had four children but two died in infancy. No-one expected Lavinia to collapse at forty-one with a cerebral haemorrhage. She was taken to the Union (workhouse) hospital and died there in June 1912. Wilfred, the youngest of Eliza’s children was a cabinet maker clearly looking for a challenge, because in 1912 he emigrated to Ontario, Canada. Rosanna and her husband Charles Board, a coachman, were living at 11 Angel Crescent, but in 1913 they emigrated to Iowa.

Eliza and James would have known many friends and acquaintances who had children in North America, but still it would not have been easy to say good-bye, especially after losing Lavinia as well. Eliza could only hope that one day she would see Wilfred and Rosanna again. Harry was still close by as were Emily and Florrie and their families. Eliza could not have predicted the turmoil of the next five years.

The Great War

When war broke out in August 1914, most of Eliza’s sons and sons-in-law were too old to enlist and most of her grandsons were too young. The immediate effect was on her husband James as so many younger men enlisting meant more work for those who remained. Soon there was rationing and shortages, as well as fear of losing her sons and grandsons and uncertainty about the future.

Wilfred was the first member of the Day family to volunteer. He joined the Canadian Expeditionary Force in February 1915. He was 26 and he declared two years of experience in the Bridgwater Rifle Association. He arrived in England with the 39th Battalion in July 1915. While Wilfred was training on Salisbury Plain, he could get leave to visit his family in Bridgwater, which was wonderful for Eliza and James. Wilfred embarked for France in February 1916 and joined the 21st Canadians. After five months in the trenches, Wilfred was sent to a Field Ambulance unit in July with a fever. Over the next weeks he was troubled with bruising to his knee and a torn cartilage, but he was also noted to have shell-shock. This may have saved his life as he was sent back to England in October 1916 and eventually home to Canada.

Harry Day and Emily’s husband, Edward Broughton, volunteered in November 1915. They were both cabinet makers working for the West of England Cabinet Co. in Bridgwater and were among six employees who enlisted in the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) on the same day. The RFC’s planes, for instance the Sopwith Camel, were built of wood, fabric and wire, so skilled cabinet-makers were essential. The Cabinet Co. held a smoking concert at the Railway Hotel for the men on their last Saturday night at home and about one hundred employees and their friends attended. There was a program of songs, suitable toasts and a few short speeches in which the six new soldiers were praised for their patriotism.

“Although their friends regretted parting with them for a while, they all felt they had taken the right step in giving their country the direct benefit of their skill and handicraft. The new soldiers left Bridgwater on Monday.”[i]

In August 1916 Air Mechanic Harry Day (pictured) was under orders for France.[ii]

After the death of Lavinia, her husband John had moved to Pontypool, Wales, an iron and steel-making town. Even though he was over forty, he enlisted in the Royal Engineers as a sapper. He was discharged in 1916, presumably for medical reasons. Eliza’s grandson Baden Powell Hawkins was a coal-cutter who enlisted in the Royal Navy in November 1917. He served at the Stokers and Engine Room Artificers School in Devonport.

Harry, Edward and Baden all returned to Bridgwater. Rosanna and her husband Charles Board also came home. They sailed in the Carpathia, the Cunard liner that had come to the aid of Titanic survivors four years earlier. German U-boats patrolled the north Atlantic during WWI so Rosanna was taking a significant risk. Perhaps she had heard that one of her parents was ill. They docked at Liverpool on 16 September 1916.

After the War

Eliza and James and their family had survived the war years, but life did not return to the way it was. There was unemployment nationally as the soldiers were demobilized and Eliza’s granddaughters and their friends would no longer work as housemaids, not after all the factory work and other occupations had opened up to them when the men left to fight. Even Harry, a skilled cabinet-maker, was unemployed for a time.

In August 1919, Eliza and James received news that their son Frederick, 43, had died of TB at Cotford. He was buried in an unmarked grave at Cotford St Luke. Even if Eliza and James wanted to bring him back to Bridgwater for burial, perhaps they felt that after twenty-two years, Cotford was his home. For by now James, 74, was not able to work as he once did. He too was admitted to what was later called the Tonedale Hospital at Cotford, but probably with a different, age-related illness. How long he spent there is not known, but he died of a short but severe attack of bronchopneumonia, four days before Christmas in December 1920. James was brought home in his coffin and was buried in the Wembdon Road Cemetery on 30 December 1920.

John Weekes Hawkins, 48, was working as a carpenter at the steel sheet works at Pontypool, but had contracted TB and also died in December 1920. He was survived by his son Baden and his daughter Annie, who was living with Lavinia’s sister Eliza Marshall and her husband in Bristol.

Eliza’s final years

Most of Eliza’s family had moved away from Bridgwater or died. Emily and Edward Broughton moved to Cardiff leaving mostly Harry and his wife Laura, who did not have children, to be Eliza’s carers. Florrie’s husband and son were still living in Bridgwater but Florrie was not with them. Those family members still living in Britain were probably visiting Eliza and sending many letters and photos of her grandchildren as well.

When World War II began in 1939 it was her grandchildren’s and great-grandchildren’s generation that joined the army or worked in hospitals, munitions factories and other essential services. At ninety, even the basic activities of daily living such as dressing or cooking a meal could be difficult if she wasn’t feeling well. Harry and Laura were there for the things she just couldn’t do such as putting up blackout curtains. They probably helped her with shopping as the new system of rations was quite complex for an elderly lady. Eliza must have been very determined to remain at home, but it was understandable as she would have had so many memories of her husband and children in every room. Fear of the workhouse and nursing-homes was common and over the years, Eliza would have seen more than one friend or neighbour taken there, not to mention her son and her husband being sent to Cotford. Her doctor would have done home visits and perhaps she had a district nurse too. They would have encouraged Eliza to go and live with her son, as health professionals were not then taught the importance of choice and the comfort of home for many elderly people.

Eliza lived alone at 7 Angel Crescent right up to the last week of her life. On Wednesday, 8 March 1944, she was walking along Fore Street in the early afternoon when she felt “all of a flutter.” A kindly man named Charles Padfield walked her home, helped her to her chair and suggested she rest. Later the same afternoon, a neighbour’s 12 year old son, Ronald Henson, was selling firewood. He knocked on Eliza’s door but there was no answer. The door wasn’t locked so he went in and found her sitting at the bottom of the stairs where she had fallen. She was crying and asked him to please help her up. Ronald called Charles Woolley, 78, who lived two doors down and together they lifted her into her chair. A doctor and her son Harry were called, and Eliza was taken to the Bridgwater Hospital. She was bleeding from a scalp wound and suffering from slight shock. Over the next few days she became more confused, wanted to go home and gradually became weaker. She died five days after admission on Monday 13 March 1944.

Then as now the coroner and the police have to be informed when someone dies as a result of an accident, which includes falls. The inquest was held on the Thursday of the same week. Harry Day, of 30 Edward Street, Bridgwater, was quoted as saying his mother was very independent. Several times he had asked her to come and live with him. The coroner summed up:

“I should imagine she tripped over the stairs, fell down and hit her head.”

The official cause of death was shock following senility, due to injuries received in a fall. The verdict was accidental death. Whatever made her feel dizzy or light-headed in Fore Street that afternoon, probably happened again at home when she was on the stairs and resulted in the fall. In hospital, the combination of an illness, a head injury and being in a strange environment was too much for a ninety-five year old and she became delirious and eventually died.[iii]

Eliza was buried in the Wembdon Road Cemetery, probably aged 94 rather than the 95 years she claimed, but no-one really minds. The only one of her children known to have shared her longevity was Mrs Emily Jane Broughton, who died in Cardiff aged 95 in 1975.

by Jillian Trethewey and Clare Spicer 1/9/2025

Sources:

- Blake Museum, Bridgwater.

- British Newspaper Archive.

- Census records and Parish registers.

- Military records.

[i] Bridgwater Mercury 3 November 1915

[ii] Bridgwater Mercury 9 August 1916

[iii] Taunton Courier 18 March 1944