George David (1798-1884) Corporal in the 40th Regiment of Foot and a Waterloo Veteran

With special thanks to Peter Randle and to David family descendant Steve Cross.

For most of his years in Bridgwater, George David was a retired grocer lodging in the town. But on each anniversary of the Battle of Waterloo, he was recognised as a hero. Corporal George David served with the 40th Regiment of Foot for a total of thirty-one years, at home and abroad. As well as garrison duty in Britain and Ireland, then the battle of Waterloo, he spent two years in the army of occupation in France, four years guarding convicts in New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land and six years in India. After he died, his friends found among his papers an official letter from his commanding officer, praising George for capturing an armed and desperate bushranger.

Ubley, Somerset

The surname David suggests Welsh ancestry, which may be the case, but George was born in the village of Ubley, Somerset. His parents were John David and his wife Edith nee Small. George was the youngest of their nine children and was born on 28 June 1798. Ubley is north of Bridgwater on the other side of the Mendip Hills. His family were villagers rather than soldiers, but for most of George’s childhood, Britain had been at war with the French. Was George inspired by someone to serve his country or was he just eager to see more of the world? George enlisted in the 40th Regiment of Foot at Axbridge Fair aged sixteen.

George David joins up on the 25th March 1814.

When George enlisted with the 40th Regiment in the spring of 1814, he was joining a regiment who were still actively fighting the last battles of the Peninsula War.

40th (2nd Somersetshire) Regiment of Foot, 1st and 2nd Battalions.

The 1st Battalion of the 40th Foot Regiment fought in the Napoleonic wars against Napoleon Buonaparte and the 40th was one of only three regiments to serve throughout the whole Peninsula Campaign. Napoleon surrendered on the 6th of April 1814, and the 40th Foot took part in the battle of Toulouse on the 10th of April 1814. Soon after this victory the regiment were redeployed.

During the Peninsula War, the 2nd Battalion had served as a home or depot battalion for the 1st Battalion, recruiting and training new soldiers and accommodating those returning for garrison duty or retiring to veteran battalions. In spite of bearing the county name of Somerset, men were recruited from a wider area in England and Wales, and from Northern Irish militias.

1814

After attesting in Taunton on the 24th of March 1814, one of the first things George and his fellow raw recruits would have experienced was a lot of marching. Before the days of rail, the army had to cover long distances on foot, as quickly as possible. George would have been sent, together with a batch of other new recruits, to join the 2nd Battalion in Ireland. The 2nd Battalion was in Dublin until mid-July 1814, when they marched to Athlone Barracks (now called Costume Barracks) to join the 1st Battalion. Both battalions then transferred to Mallow. Here, 82 men were transferred from the 2nd to the 1st Battalion, but this did not include very new recruits like George. The 1st Battalion then left Ireland in early October, destined for the war against the United States, towards New Orleans. The much-reduced 2nd Battalion moved to Devonport, Plymouth, in November 1814. Then George and the 2nd Battalion moved in the spring of 1815 to Dover Castle.

The 1st Battalion were in Mobile (now in Alabama) until April 1815, then they sailed and had a fast passage back to Spithead, arriving on the 15th of May 1815. On arrival they were surprised by the news of Napoleon’s escape from Elba and the alarming state of affairs in Europe. George David was officially transferred to the 1st Battalion from the 22nd May.

When he joined the 1st Battalion, George was assigned to the company commanded by Irishman Captain Robert Phillips, who at the age of 28, was already a very battle-hardened veteran. Captain Phillips had joined the 40th Foot Regiment in 1805 and fought in most of the battles of the Peninsula War, including the appalling slaughter of the storming of Badajoz in 1812, which caused even the Iron Duke of Wellington to weep, and was seriously wounded in the Battle of Sorauren in 1813, during which the 40th made no less than four separate bayonet charges. In Captain Phillips, George David had now come under the command of a very experienced soldier, ready for battle.[1]

Battle of Waterloo – 18th June 1815

By 1804, Napoleon Bonaparte had risen from revolutionary general to Emperor of the French, forging a new empire through sheer ambition and military brilliance. Over the next several years he stormed across Europe, defeating one coalition after another and reshaping the continent in his image. Yet his fortunes changed in 1812, when his grand invasion of Russia collapsed in catastrophe, shattering the aura of invincibility that had surrounded him. Even so, Napoleon continued to resist the combined powers of Europe with remarkable tenacity until, in 1814, he was finally overwhelmed and forced to abdicate. Exiled to the small Mediterranean island of Elba, he watched as the old Bourbon monarchy returned to France.

But Europe’s fragile restoration was short-lived. In February 1815, Napoleon escaped from Elba and marched triumphantly back to Paris, reclaiming power in a matter of days. His dramatic return—later known as the Hundred Days—galvanised the great powers into action: Britain, Prussia, Austria, Russia, the Netherlands, and numerous German states once again declared war, determined to end his rule for good. Facing a vast coalition, Napoleon understood that his only hope lay in striking swiftly, defeating each enemy before they could unite their forces. Acting on this strategy, he advanced north into Belgium, aiming to crush the Anglo-Allied army under the Duke of Wellington—an army composed of British, Dutch-Belgian, and Hanoverian troops—before it could join with the approaching Prussian army. The stage was now set for the climactic confrontation that would decide the fate of Europe: Waterloo.

The Spring and Summer of 1815 were wet. The transport from Spithead to Ostend was choppy, and what should have been a day’s sailing took four. George and his comrades would have suffered badly from seasickness and would have been very glad to be on dry land at last, at least for a brief moment. They were then transferred to canal boats, to be taken to Ghent via Bruges. With Napoleon’s lightening advance, King Louis XVIII of France had fled to Belgium and was in Ghent, so the 40th Regiment briefly served as royal guards. They had good quarters, good food and relatively light work on guard and helping with building fortifications for the town.

The relative peace was shattered on 16 June when urgent orders were received to march to Brussels immediately, and the 40th made 30 miles in a single day, not quite reaching Brussels.

George’s uniform consisted of a thick red-wool coat, with buff-coloured cuffs, collar and turn-ups at the back; grey trousers and a tall felt hat called a ‘shako’, which had tassels and a brass plate with the regimental insignia on the front. He was then laden with a famously uncomfortable backpack of black canvas round a wooden frame, which carried spare shoes, shirts, trousers and personal items. Two white leather cross belts on one side carried his bayonet, and on the other his ammunition box, which held 60 musket balls in pre-prepared little paper cartridges with gunpowder. Also slung over his shoulder was his haversack, which held his food rations; and another strap held his wooden barrel-shaped water bottle. Dangling from his backpack straps to his front were strings holding a wire brush and a little pick, that helped him unclog his musket if it fouled up with residue gunpowder.

George was armed with a ‘Brown Bess’ musket. The cartridges containing powder and ball had to be loaded down the muzzle and rammed into place. When he then aimed and pulled the trigger, a flint struck a metal plate, causing a spark that set off the gunpowder. With this tedious re-loading routine, George would have been able to fire about three times a minute. It was tiring work as the musket was heavy. It was also dirty. Each shot produced a lot of smoke, and as the battle wore on the barrel would have become very hot to the touch. For most of the battle George will have had his bayonet attached to the end of the muzzle, in effect turning the gun into a long spear. In all George was carrying around 30kg of equipment, about 4.5kg being the musket.

While George David was marching under all this weight to join Wellington’s main army, the opening clashes of the campaign erupted. Napoleon struck first at Ligny, where he hurled his forces against the Prussians in a brutal, hard-fought battle that ended with the Prussian army mauled and forced to withdraw. At the same time, to the west at the crossroads of Quatre Bras, Wellington’s troops became embroiled in a fierce struggle against Marshal Ney’s French troops. The fighting there was close and bloody, marked by desperate infantry squares and repeated cavalry charges, as both sides sought to secure the vital junction. Although the Allies ultimately held the field at Quatre Bras, the two battles together set the stage for the decisive encounter still to come.

George and his comrades rested for only a couple of hours at night, before marching another twenty miles to Waterloo. It rained heavily the night before the battle, and because it was summer George and his comrades had not been issued greatcoats. They were sodden from the rain and had barely slept the night before. The men tried to pitch canvas tents as best they could, but they were wet and muddy already, and the ground below them was soaking wet. Once they were under cover the rain got in anyway. Some men managed to get some fires going, which yielded more smoke than flame, but at least provided more warmth.

It was still dark when the men were ordered to prepare for battle and get into formation. On the morning of the battle the 40th was made up of 747 men, 55 non-commissioned officers and 38 officers. They were part of the 6th Infantry Division of around 5,158 men, which had been cobbled together from a variety of forces not long returned from America and some German troops from Hannover. They were under the command of Major-General Sir John Lambert.

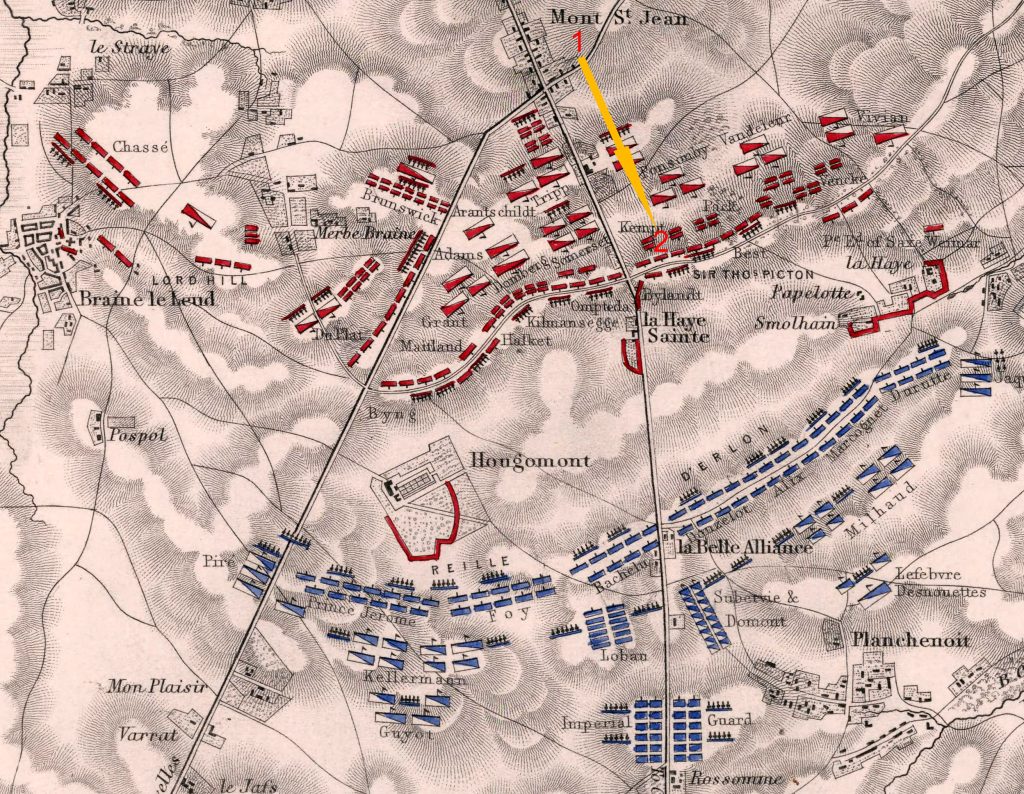

Wellington would not be able to defeat Napoleon’s larger army by himself. He needed that mauled Prussian army to help, and it was essential to hold the French off until those reinforcements could arrive. So Wellington took up a defensive position along a ridge, which had fortified farmhouses at the ends and the centre. George David would end up positioned near the central one, called La Haye Sainte. Napoleon aimed to simply smash through the allied army on the ridge, knock Wellington out of action, before turning to finish off the Prussians. However, all that rain made moving troops and cannon difficult. And even then, as cannonballs were intended to skim off the ground before hitting their target, if it was too wet, they would just splat into the mud. So, for most of the morning the battle was postponed while the ground partially dried. All this was essential time Napoleon could not afford to lose.

The 40th regiment took up its position in the reserve of Wellington’s army at 10am. The men would have had a brief breakfast, then would have had to wait around for hours, in a mix of boredom and giddy anticipation. George’s nerves would have been steadied by the men around him who would had served in Spain and America, and who had fought before. Still, he would never have experienced anything as intense as what was about to happen.

Accounts of soldiers in the 40th Regiment are a little confused. It was a long day, and a terrifying one, so it’s not surprising that afterwards they might jumble up the order of things or condense things down. Below is an attempt to reconstruct things from George’s perspective.

THE BATTLE BEGINS

George and the 40th Regiment were initially in the reserve of the army near the farm of Mont St. Jean. At about noon the battle commenced with artillery fire. For the next couple of hours, the 40th remained in place, behind the front lines. Mont St Jean was used as a field hospital, so George may have seen a steady stream of horribly wounded men limping or being carried to the farmhouse.

At about 2pm the British line in the centre of the battlefield was breaking. The British heavy cavalry charged forward, saving the situation, but ultimately galloped too far into French positions and became overwhelmed. While this was happening the 40th moved forward to plug the gap and hold a position along the back of the ridge behind La Haye Saint.

They were now exposed to the long-range French artillery. Cannonballs were mostly solid balls of iron and were meant to skim along the ground. Only a few would be explosive bombs filled with smaller iron balls. As George and his comrades were packed into a column, a single shot could do terrible damage. Around this time one shot killed 19 men in a row, another killed 23 in one shot. At points in the day, when they were able, the men were told to lie down to minimise the impact of the passing balls.

Everyone who remembered the battle recalled how the fields and roads were in a terrible state of dirt and mud, which made moving difficult and exhausting. For the next five hours George and his comrades would remain in this muddy spot, already churned up by hours of activity, moving into different formations as needed. Soldiers recalled that as time wore on, they were almost knee-deep in mud.

THE HEAT OF BATTLE

Some let up from the artillery came at about 4pm, but that was because the French cavalry were about to attack. They launched mass charges against the allied positions on the ridge. When being attacked by cavalry, the allied infantry would form hollow squares, with men kneeling in the front rank, then two or three rows behind firing volleys of musket balls. They were tightly packed, and the hedgehog of bayonets were almost impenetrable to the horses.

There were three squares close to each other, the 40th, 27th, and 4th Regiments, around which the cavalry would swirl. The horsemen were terrifying in their flamboyant uniforms – some even in armour – which would have been an awe-inspiring sight for young George to behold. The Frenchmen slashed and cut at the kneeling men with their swords and lances and fired pistols into the packed British ranks. However, the square held, and the men behind those kneeling ones kept a steady rate of fire. The horsemen were quickly driven back. Around George’s square were littered the dead or dying bodies of his comrades already caught by cannon fire, and now the French horses and men.

Several waves of cavalry attack followed, but also the French infantrymen who had caught up. Although being in a hollow square formation was great against cavalry, because it was so tightly packed it was vulnerable to musket fire and cannonballs. The 40th had to quickly re-deploy into a line to meet them. George, as part of the line, would have held his musket as the Frenchmen advanced but had to hold his fire until told to shoot. These moments would have been nerve-wracking for the inexperienced man. However, when the moment came to fire, the whole line shot at once, creating a wall of lead that devastated the advancing French Column. As re-loading took so long, the British then charged forward with their bayonets to make sure the French fled before reforming, even though the French by now would be firing back themselves. As soon as they were seen off though, the next cavalry wave would arrive, so George and his comrades had to rush back and form the square again. As each wave came and went, the 40th regiment was starting to thin as more and more of its men were killed. But in any moments when they were not being attacked by infantry or cavalry, with open ground in front, the French artillery would open fire again. When a man fell in George’s line, the surrounding soldiers would tighten the ranks to make sure there were no gaps.

In the brief moments of respite between the waves, boxes of ammunition would be placed nearby for men to run to and return to their squares or lines. This might also provide a moment for men to take a quick drink for their water bottles or to walk a little distance to relive themselves. They were already smeared black by musket powder smoke.

DEFEAT?

Nearby, La Haye Saint, the fortified farm at the centre of Wellington’s army, defended by the King’s German Legion, ran out of ammunition and fell to the French at about 6pm. This was a critical moment in the battle, as it removed a major obstacle to the French smashing through the middle of Wellington’s army. It also meant the French could bring up their cannons and fire at very close range into the allies’ squares. They would use canister or grapeshot, which were lots of small balls packed into the cannon and fired at once, which could be devastating. The allies now couldn’t leave their squares as French cavalry was still nearby. They were sitting ducks.

The 27th Inniskilling Regiment, which was next to the 40th and closer to La Haye Saint, was directly in such a line of fire. They were also beset by French skirmishers on a small knoll, who poured very directed fire into that Irish regiment. They lost two thirds of their strength in only a couple of hours. The Somersets just next to them suffered badly as well. This would have been the most harrowing part of the day for young George. Already exhausted from hours of shooting and squelching round the quagmire, they were now under intense fire. Men around him would have been shot in the most terrible ways. Unlike modern bullets that are pointed, musket balls are round and cause much more damage when they hit a person, tearing into the body rather than cutting into it.

Fortunately for Wellington, the Prussians were now starting to arrive in force to the east of Napoleon’s army. The battle hung in the balance. Napoleon still had time to smash the tottering army of Wellington and turn to see off the Prussians. At a little before 7pm Napoleon committed his famed Imperial Guard to sweep Wellington off the ridge. There was a brief respite for the 40th. They formed into line and quickly advanced to the brow of the hill, where a shattered hedge and tree line were much torn by cannon fire and hours of troops advancing back and forth over it. As before, the Imperial Guard advanced up the hill while George and his comrades took steady aim with their muskets, waiting for the order to fire. As before, as the Frenchmen steadily marched forward within their range, the British troops opened fire with devastating effect. They reloaded and fired again, before charging forward again, fighting the bravest and closet of the Frenchmen with bayonet. The sheer amount of smoke obscured George from seeing too far in front, but they had done it – the Guard were falling back. After a few yards they halted and reformed their line, catching their breath.

Now at around 7pm, after hours stuck in the same muddy place, the Duke of Wellington rode up to the 40th and gave the order to advance. The men gave the duke three hearty cheers. The tide of battle had turned.

A TERRIBLE VICTORY

Although the battle was won, George was not out of danger yet. What was left of the 40th formed into a column and started to advance down the hill. Men to the right attacked and re-took the farmhouse of La Haye Sainte. They were still under fire from French artillery. While the 40th was advancing, a cannonball took off the head of one of the regiment’s captains, killing 25 men at the same time. They kept advancing until nightfall, although the fresher Prussians took the lead. One of George’s comrades recalled ‘we followed them ourselves for about a mile and then encamped on the enemy's ground; and if ever there was a hungry and tired tribe of men, we were that’.

Of the roughly 840 men of the 40th who went into battle with that morning, 193 were killed. Shortly put, George had lost between 1/4 and 1/5 of his comrades. George presumably had a haunted but deep sleep that night. The next morning revealed a scene of carnage on the sodden battlefield. George David was detailed to help bury the dead and euthanise wounded horses. He had survived, but the scenes of utter carnage would have stayed with him for the rest of his life.

After the battle, the Army of Occupation June 1815 – December 1816

What a difference a day makes. Before the battle, George was a seventeen-year-old boy who, after a year of training with the 2nd Battalion, probably thought himself ready for anything. The experiences of that single day would have stripped away the last vestiges of childhood and any dreams of glory and left behind a deeply shocked young man with a head still filled with the sights and sounds of battle, which probably haunted his dreams for many years to come.

Although Napoleon had again surrendered, Wellington could not be sure that the war was over and at first, he expected some towns to make a stand. The 40th, with the rest of Wellington’s army, marched towards Paris, camping in areas where resistance had been expected, but encountered none. Wellington was anxious to take control of Paris, and he pressed onwards in a series of forced marches, in spite of very hot weather. After a military convention, Wellington announced that the Allies would take possession of Paris on the 7th of July.

The 40th reached Paris with the rest of the army and camped in Neuilly Park, then half a mile from the gates of Paris. On the 24th of July a big review of the army was conducted in Paris, including a grand march past Wellington and royalty from Russia, Prussia and Austria. While the army was camped outside Paris, Wellington was reported as riding around all the lines every day. Another big review was carried out in September, the purpose being to keep the men occupied and active, and to demonstrate strength in numbers to deter any possible uprisings. The return to some sort of normal army life may have helped the young soldiers to recover. Their normality was movement and order, marching, patrolling, guard duties, endless drilling and looking forward to the next meal.

The army was still living in tents until the end of October, when the weather was beginning to become more wintery. At last, they were able to move to better quarters at Saint German, but they moved again in December through Paris to the villages of La Valette and Saint Chapelle. George is recorded in these villages on the muster rolls for the 40th Foot Regiment. By January 1816, Wellington’s Army of Occupation had been selected, and this included the 40th. There were frequent changes of location in the first part of 1816, although their headquarters was established at Havrincourt. To replace the losses suffered during the battle, two large detachments of men arrived from the 2nd Battalion, which was then disbanded. On the 17th of May the Waterloo medals arrived and were distributed. These were the first medals to be awarded to all ranks for a battle or campaign, rather than for individual acts of bravery. Every soldier was also credited with two extra years of pay and service, to count for pensions and seniority, and these soldiers were to be known as ‘Waterloo Men’.

The weather was cold and wet in June 1816, but in spite of this there was an unrelenting programme of at least 4 hours of drill every day. This included manoeuvres used in battle or approaching battle:

- marching in full, half or quarter distance columns,

- deployment of close columns into line,

- wheeling close or quarter distance columns into a flank,

- forming into line from open column,

- forming square from half or quarter distance or close column,

- marching in line.

In October 1816 a review was held at Denain of the entire allied armies, again inspected by Wellington. Early in 1817 it was decided to reduce the army of occupation and the 40th returned to the UK via Calais.

Return to UK - Scotland Jan 1817 – May 1820

After fighting for six hard years throughout the whole of the Peninsula Campaign and then the battle of Waterloo, the 40th were due for a period of ‘home service’. They established their headquarters at Glasgow, and were there for over two years, as soldiers enjoyed the long overdue opportunity for furlough and seeing family again. They would have continued to drill and march to maintain fitness and discipline, and now that the 2nd Battalion had been disbanded, the 1st had to train new recruits as well. In 1818, new colours were finally presented to the regiment, with the words ‘The Peninsula’ and ‘Waterloo’ engraved in gilt letters. The old colours were so worn they were just bare poles. In October 1818 the size of the regiment was reduced. In May 1820 the regiment marched south to Manchester, then on to Rochdale.

Ireland November 1820 – March 1823

In November 1820 the whole regiment prepared to move to Ireland. They embarked from Liverpool in several small boats and arrived in Dublin two days later. Then on to Limerick, where the regiment was split into several detachments which were scattered around. Occasionally a detachment provided escorts for prisoners being moved from one place to another.

On the 12th August 1821, the regiment was again reduced in size, superfluous officers were put on half pay, while surplus NCOs and privates were discharged. It may have been at this point that Captain Robert Phillips went on to half pay. After fighting in at least twelve battles and being wounded six times, Phillips still had a bullet embedded in his body, which remained with him for the rest of his life. He eventually went on to become barrack master in Dumbarton. George David had survived two culls, he was young and fit, and a good soldier. The regiment continued to move around from place to place in Ireland. Then on the 28th January 1822 the whole regiment returned to Athlone, where their headquarters was set up.

In March 1823 they received orders that the regiment would be sent to New South Wales to form guards for convict ships.

Colonial New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land

Accordingly the regiment marched to the Royal Barracks in Dublin, then embarked on eight packet boats to sail to Liverpool. Then it took the soldiers twenty days to march the 250 miles to the Chatham army barracks. Over the next three years, nearly six hundred officers and men of the 40th Regiment sailed to New South Wales (NSW) as guards on convict ships. The government hired merchant ships to transport troops and convicts. Each ship carried a detachment of at least one officer and thirty or more soldiers. George was one of fifty other ranks and two officers who embarked at Gravesend in early January 1824 on the Prince Regent, a relatively new, 400 ton ocean-going sailing ship.[2] Her wooden hull was covered with sheets of copper to protect it from barnacles and increase the ship’s speed. She was even armed with ten 18-pounder carronades in case of trouble. They sailed for Ireland and took on 180 male prisoners at the Cove of Cork, as well as water and provisions. From there the Prince Regent began the long voyage to New South Wales on 13 February 1824. First stop was Rio de Janeiro. It was an opportunity for necessary repairs as well as replenishing supplies. George left England and Ireland in winter and sailed into tropical summer heat. They left Rio on 26 April and sailed south to pick up the roaring forties, which blew them east to Australia. Two prisoners died during the voyage but otherwise it was uneventful. George finally reached Port Jackson (Sydney) on 15 July 1824, six months after leaving England. [3]

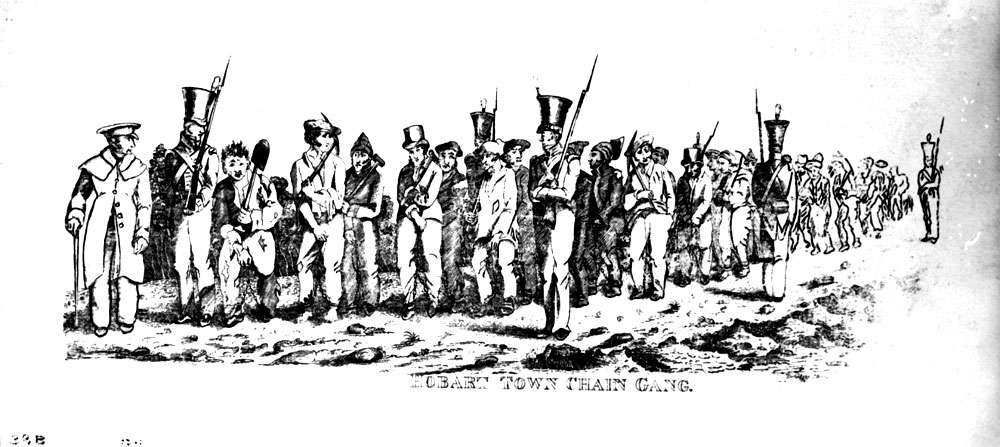

Sydney had already grown from a penal settlement into a town. Governor Macquarie had ordered the streets in the town centre to be surveyed and used convict labour to build substantial sandstone and brick buildings that George marched past and which can still be seen today. The army was responsible for guarding the convicts in the Hyde Park Barracks. Detachments of soldiers were sent to Parramatta and other nearby farming areas, as well as further away to Bathurst, Moreton Bay (Brisbane) and Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania). The soldiers were primarily guarding convicts but also protecting the colonists from escaped convicts and bushrangers. It was difficult for an escaped convict to leave New South Wales because of its isolation, so they lived in the bush and stole food from the farmhouses. When they were armed and resorting to robbery and violence they were called bushrangers.

Convicts were often moved under guard to and from Sydney and the other prisons and settlements. George was on one of those voyages to Hobart in July 1825 as the 40th Regiment gradually regrouped in Van Diemen’s Land. Hobart was also a growing town with government officials and their families; soldiers and sailors; convicts, ex-convicts and an increasing number of people who had been born in the colony. There were shops and pubs but a shortage of single women.

George spent six months on guard duty in Hobart, before he was sent “in the bush” probably to guard convicts building roads. In July 1826 he was deployed to Port Dalrymple (later Georgetown) at the mouth of the River Tamar on the north coast of Van Diemen’s Land, for three months. Next he was guarding convicts in small settlements near Hobart. George had a spell in hospital in July 1827 but he must have recovered because in October he was sent to Pittwater (present day Sorell). It was a small coastal settlement just north of Hobart surrounded by farms growing grain to feed the colony. Many settlers were assigned convicts as farm labourers. George was one of four soldiers, a corporal and three privates, who were responsible for guarding the convicts and assisting the local constable and the magistrate to maintain law and order. In George’s time there was a wharf for the ferries that carried goods and passengers across Pittwater to and from Hobart. There was a school, a barracks, a gaol and St George’s Anglican Church. There were also licensed public houses. Sorell was on the land of the Mumirimina people and in the 1820’s there were episodes of violent conflict between the indigenous people and the settlers. Often this was not documented and whether or not George was ever involved is unknown.

The road to the notorious Port Arthur prison went through Sorell. Conditions for the convicts were harsh and escape attempts, however dangerous or futile, were common. The settlers were afraid of being attacked by bushrangers and escaped convicts looking for food, money, horses and anything they could sell. On Christmas night of 1827 at Green Ponds, about thirty miles north of Hobart, there was a break-in and theft at the home of prominent merchant and landowner Captain A. F. Kemp. The thieves escaped with quite a haul, including silver, expensive clothing and two guns. A few days later, Captain Kemp placed an advertisement in the Hobart Town Courier, listing the items stolen and offering a fifty pound reward for the capture and conviction of those responsible.[4]

A couple of weeks went by, then the constables at Jericho, a few miles from Green Ponds, received a tip-off about a bushrangers’ campsite. They had been looking for two escaped convicts, Thomas Pearson and Henry Williams, for weeks. They lay in wait and captured Williams, but Pearson rode away. While the others were chasing after Pearson, Constable Loggins guarded the prisoner. Williams had hidden a steel blade up his sleeve and despite being in handcuffs, fatally stabbed Loggins and escaped. Williams was recaptured two days later and most of the stolen goods were recovered at the campsite, but Pearson was still on the run.[5]

In early February, Chief District Constable Alexander Laing was informed by a shepherd that he had seen Pearson at Pittwater. Laing, with the three local soldiers, including George David, and two trusted convicts, promptly set off, armed and prepared for resistance. Pearson was quickly spotted with another convict named McDonald. The incident was reported in the colonial newspapers:

“With feelings of no ordinary pleasure we inform our readers that Pearson, the notorious bushranger, was taken on Saturday last, about a mile below the ferry, at the lower settlement of Pittwater, in consequence of the information of a prisoner of the Crown, who, we are confident, will be promptly and liberally rewarded. … (McDonald) took to his heels with all speed, upon which one of the party fired after him and hit him on the leg, which stopped him. Not so with Pearson. Having been shot at and missed, he retreated. … When he was run up to, he presented his piece, but, kept his fire, still retreating. George David at length ran him down, Pearson still keeping his piece levelled at David till within a yard of the muzzle, when he snapped and the priming burned, but the shot did not go off, otherwise, without all question, David had been killed. The resolution of David is above all praise, and such service cannot fail of due reward, both from His Excellency and the commanding officer of the regiment.”[6]

Pearson was quickly arrested and taken to Pittwater.[7] He had abducted McDonald because he was a sailor and would be useful in Pearson’s desperate plan to steal a boat and row or sail across Bass Strait. McDonald recovered and was sent back to Public Works. Laing was keen to claim the reward money. His superiors determined that the two surviving constables in Jericho had earned a share, as well as Laing, the soldiers and the shepherd. Laing went up to the barracks and saw Major Kirkwood, who went with him to the Attorney-General for written authorisation.[8] Captain Kemp paid the reward and the pay list for June 1828 showed an extra payment to George. [9] After all the hardships of a soldier’s life, George finally had some money of his own to spend as he chose.

George remained at Pittwater until April 1828 when he was sent to Oyster Bay near the Darlington and Maria Island prisons.

The Phoenix

George could reasonably expect to return to England every few years, but instead, the 40th regiment was ordered to India. The logistics of finding and provisioning enough transport ships and the need for an orderly transition of duties to the next regiment, meant that the soldiers didn’t all leave at once. The officers of the Regiment’s headquarters and their families, plus 200 other ranks including George, embarked on the ship Phoenix from Hobart on 29 September 1828, bound for Bombay (Mumbai).[10] They were lucky to survive.

The Phoenix, 490 tons, Captain Thomas Cousins, was a merchant vessel that had arrived at Port Jackson with 190 convicts in July 1828. It was her third voyage to Australia, so she had a proven track record. The passage to India “was most tempestuous and protracted” according to the regimental history.[11] The shortest route was north to Bass Strait, west across the Southern Ocean, which had a reputation for Antarctic blasts and rough weather, and then north-west across the Indian Ocean. A storm at sea meant a sailing ship had to shelter if possible or risk being blown off course. All George and the other soldiers could do was obey orders, keep busy and pray. In the tropical latitudes the ship was becalmed, making the voyage even longer, and soon fresh drinking water was running low.

“… it was found (necessary) to reduce the quantity of water allowed to each person on board. Accordingly on the 6th December a reduction of one third of the usual quantity took place and on the 8th from the prevalence of light winds and in consequence of uncertainty of relief a further reduction of one pint from each adult and half pint from each child took place. This continued until the 21st December when calms and light wind still prevailing and having at the rate of issue only four days water in the ship it became a matter of paramount necessity again to decrease the allowance which was now reduced to two pints per day for each man for all purposes. Being in Lat 5.58 N. and 75.08 E. and the weather consequently extremely warm, the troops suffered incredibly from thirst.”

Just in time the Phoenix reached Indian waters and there was no alternative but to run the ship for the nearest port. Imagine the relief for everyone on board when they sighted land. The ship anchored off a small town on the Malabar (southern) coast. They were able to take on board only a small quantity of water, but it was enough to save lives. Unfortunately the ordinary seamen remained fearful that the horrors of the previous weeks would be repeated. Except for the ship’s officers, two seamen and a boy, the whole crew mutinied and were confined below deck while George and his fellow soldiers loaded the barrels of water and manned the ship. Two days later the Phoenix reached the port of Quilon (Kollam) twenty miles to the north, where they took on adequate water and provisions with the help of the local East India Company depot. They sailed again for Bombay with an unwelcome stowaway: cholera. One private died on board and when the ship moored at Bombay on 21 January 1829 several soldiers suffering with cholera were sent straight to hospital. The next day George and the rest of the soldiers marched into barracks at the fort.

India

Before long another ship took the regiment south to Vingola (Vengurla). They disembarked and marched the eighty miles to barracks at Belgaum (Belagavi). A muster at Scrawlee Camp, on the way on the 1st March, shows George in Captain George Hibbert’s Light Infantry Company.[12] Hibbert was also a Waterloo veteran. The light infantrymen were fast-moving skirmishers who fought in pairs and were quite unlike the regular companies who formed squares and fired in volleys. In both cases their duties were broadly to maintain law and order and to respond to any uprisings against British rule. Belgaum was the 40th Regiment’s headquarters but detachments could be sent to other towns as needed. George was still in Captain Hibbert’s company the following year. Whilst at Belgaum one ensign, four sergeants and fifty-nine other ranks died from mostly dysentery.

After two years at Belgaum, the regiment received orders to travel to Poona (Pune) and take over from the 2nd Queen’s Regiment. They marched back to Vingola and eighteen small sailing ships called patamars took them to Bombay. The soldiers then had to march over ninety miles to Poona. Only the officers had horses. They arrived in March and George was promoted to Corporal on 1 April 1831. They returned to Bombay in December 1833.

During 1834 the hard garrison duty and the depressing climate of Bombay was reported to be having a bad effect on the health of the men. George was thirty-six and it must have been difficult to remain positive and motivate the younger men when his hip joints were giving him increasing pain. Soldiers did a lot of marching and spent many hours on their feet on guard duty, both of which would make the pain worse. By 1835 George was struggling. The army surgeon wrote:

Corporal George David, 37.

Rheumatismus chronicus.

“This man has been much afflicted since his arrival in this country in 1829 by rheumatic pains particularly confined to the hip joints and loins. He is little relieved by the usual remedies and mercurial fumigation alone palliates for a short time his sufferings. He is an old soldier and not likely again to be fit for further services in this country. I recommend him to be sent to Europe for discharge.”

The regiment confirmed the surgeon’s decision at Bombay on 31 October 1835 with a further comment:

“His conduct has been that of an extremely steady, active, good soldier.”

George still had to wait for a ship and he did not land at Gravesend until 8 June 1836. It was over ten years since he was last in England. Another medical officer at Horseguards in London recommended that George was permanently incapacitated and unfit for service. He was aged 38, 5’ 8” tall with brown hair, grey eyes and a fair complexion and by trade a labourer. George was finally discharged from the army with a pension on 12 July 1836. Rather than live in the Chelsea Hospital for army veterans, George elected to return to Somerset. He was thus an out-pensioner.

Rickford, Somerset

George settled down with his wife Jane, to be a grocer and postmaster in Rickford, a little village in the parish of Burrington. This was about five miles from where he was born. Jane was the same age as her husband and was born in Somerset. Jane may have been the widow of one of his fellow soldiers. If George and Jane met in India it would explain why there is no record of their marriage in England. The household included a young woman servant to help in the kitchen and with cleaning. There is a family story that George owned horses and used to go to Bath for horse-racing up on Lansdown. Whenever in Bath he would stay at the Angel Hotel in Westgate Street.

The extended David family was large and many were still living locally. George’s elder brother Abraham and his wife and family lived in Burrington. In 1848 another brother James had a fall which resulted in a head injury. James never fully recovered and he was admitted to the county asylum in Wells and died there in April 1851. An even greater loss for George was to come. His wife Jane became ill and died in a few short weeks in August 1851.

In May 1852 George married Mary Neads from nearby Yatton. At the time George was still working, but by 1861 he had retired and they were living either in Rickford or in Burrington itself. Most of George’s brothers and sisters, except for Abraham, had died as they were all older. George’s wife Mary died in 1866 and is buried in Burrington.

Bridgwater

After Mary’s death, George moved to Bridgwater and found lodgings in the town. In 1871 he was living with the Hallet family in the fittingly named Wellington Road, near the railway station. He was in his seventies and retired but still had his army pension which would keep him out of the workhouse.

The first time that most Bridgwater residents knew they had a Waterloo veteran amongst them was in June 1876, when the Devon and Somerset News told George’s story.[13] He was one of the last of the brave veterans who were a link with a glorious victory and the nation did not want to lose them without saying thank you. In his later years, George added three years to his age, which just made him more newsworthy.

“Sunday next will be the 61st anniversary of the Battle of Waterloo. Of those who took part in that memorable and eventful campaign only eight, it is believed, remain in the county of Somerset, one of the number being George David of this town, who will be 81 years of age on the 28th. David enlisted in the 40th Regiment of Foot, the 2nd Somersetshire, at Axbridge Fair in March 1814, two years and three months before the battle was fought and besides taking part in the conflict, was one of the party engaged in slaughtering the wounded horses and burying the dead the day after the battle.”

Thereafter, each June there was a paragraph in the local newspaper in which George thanked the people who had given him gifts of money on the anniversary of Waterloo.[14]

“A Waterloo Veteran. George David of the 40th regiment of Foot and one of the survivors of the Battle of Waterloo was on Tuesday, the 63rd anniversary of the battle, the recipient as usual of several gifts from the inhabitants of Bridgwater. David is now 83 years of age and quite hale and hearty.”

George was now lodging in the home of George Sealey, a coal merchant, in Dampiet Street. This was much closer to the centre of town and to an elderly friend in St Mary Street, the widowed Mrs Mary Parminter. He spent each day with the Parminters, mother and daughter, but slept at Dampiet Street. In March 1882, George was crossing busy St Mary Street when he was knocked down by a passing vehicle and badly kicked in the head by the horse.[15] Three months later, when he thanked his friends for their customary gifts on the anniversary of Waterloo, George still had pain in his knee as a result of the accident. He insisted that otherwise he was “as hale and hearty as ever” but he never fully recovered. [16]

The accident had drawn attention to George’s need for some extra care. He was a widower with no children. Mrs Parminter had died, but George was now in the routine of spending the day with her daughter who cooked his meals and generally looked after him. Rev. W. G. Fitzgerald, the vicar, wrote on George’s behalf to the Duke of Cambridge, Commander-in-Chief of the British Army. A reply came in February 1883 with the good news that the petition was successful and George had been granted a £5 lump sum and his pension was to be augmented.[17] With all this talk of his future, George also made a plan. He ordered his coffin to be made by Mr. Alexander the undertaker, which was done.

“He also selected a spot in the cemetery where he should like to be buried, indicating this by inserting in the ground a piece of wood, on which he rudely carved his initials G.D..” [18]

The head injury had aggravated his cataracts and by the end of 1883 George had lost almost all his vision. He found it difficult to go backwards and forwards to Dampiet Street and so Miss Parminter moved out and lodged next door with Mr and Mrs Godfrey, and George moved into her cottage. Miss Parminter continued as his housekeeper by day. This arrangement worked well until April 1884.

About a week before he died, George fell and hit his head, either against the bedstead or the washstand. He told Miss Parminter what had happened, who kept cold water pads on his head where it was bleeding a little. In the following days, George continued to complain of a terrible headache. He lost his appetite and spirits and could not walk without assistance. In retrospect he probably had bleeding around the brain, which was not enough to kill him outright, but was very troubling. George was constantly saying to Miss Parminter that he was a burden now he needed so much help. On Friday evening, May 2nd, Miss Parminter left the deceased in bed between eight and nine in the evening. She locked the front door and took away the key. On Saturday morning, she returned about 7:30 am. She unlocked the door and went in to light the fire and get breakfast as usual. When this was done she went upstairs and was shocked to find George in bed with blood everywhere.

“Oh dear, what have you done? Oh, why did you do it?”

George replied, “I did it to ease the pain in my head.” Miss Parminter saw his penknife on the floor and threw it in the fire. She went next door to Mr Godfrey who sent his servant to fetch Dr Marsden, who arrived shortly after. Dr Marsden dressed the wound and later told the inquest that none of the major vessels had been severed, but the blood loss was so great that he expected the injury to be fatal. George lapsed in and out of consciousness and Dr Marsden came back later to check on him. George remained in the cottage and died the following afternoon.

The inquest was held in the Town Hall on the following Tuesday. Miss Parminter, Dr Marsden and Mr Godfrey all gave evidence. Dr Marsden testified that George had told him what had happened and this coincided with Miss Parminter’s account. Dr Marsden was of opinion that the pain from which the deceased had suffered in the head at the time lead him to seek relief. The wound in question must have been done by some blunted instrument such as an ordinary pocketknife. The jury returned a verdict of suicide whilst in an unsound mind.

The funeral took place a week later on a Saturday afternoon. About fifty members of the volunteer corps in uniform and three of their officers were present. Six members of the Borough police force officiated as bearers and Sergeant-Major Heron, West Somerset Yeomanry (one of the gallant 600 of the Balaclava heroes) and Mr Godfrey were the chief mourners. The coffin, upon which was inscribed “George David died 4th May 1884 aged 88 years,” was borne in a hearse to the Wembdon Road Cemetery, where the burial service was conducted by the Revs. W. G. Fitzgerald and E. May, vicar and curate of St Mary’s. The coffin was lowered into a grave at the spot George had selected. On emerging from the cemetery gates, the volunteers were met by their bandsmen who played as they marched back through the town to their headquarters.[19]

The burial register notes he was in 'section 2', what we now call plan G. The exact plot isn't noted. Sadly George's wooden marker must have soon fallen away: by the time of the 1930s when the names of the known graves in this plan were noted down, George was no longer remembered.

Epilogue

Amongst his documents and found after his death, was a Garrison Order signed “John Montague, Major of Brigade” and dated Van Diemen’s Land, Hobart Town barracks, 28 February 1828:

“The Governor commanding Van Diemen’s land cannot permit to be passed unnoticed the cool and soldier-like conduct displayed by Corporal George David of the 40th Foot, in the apprehension of an armed and most desperate bushranger, and desires the commanding officer to inform him that he will receive public thanks and also will be rewarded with £10. The above named document was sometimes since forwarded to the Duke of Cambridge, Commander-in-Chief, together with the length of servitude etc. And it resulted in the grant of an extra pension of £5 per annum.” [20]

Jillian Trethewey, Clare Spicer, Miles Kerr-Peterson 2 December 2025

References

Adkin, Mark, The Waterloo Companion, 2001.

British Army. 40th Regiment. Regimental Order Book, 16 February 1824 - 19 January 1827. The National Archives. Digitised and online in the Australian Joint Copying Project (File 1712/696).

British Army. Royal Hospital Chelsea soldiers service documents. The National Archives ref. WO 97/560/115. Discharge papers of George David.

British Army. WO 12 Muster rolls and pay lists of the 40th Regiment of Foot. 1732-1878. The National Archives: WO 12/5333, WO 12/5335, WO 12/5340, WO/12/5341 and WO 12/5403. Muster rolls for 1814 and 1815 available on Ancestry. Some muster rolls for the regiment’s time in NSW and Van Diemen’s Land are digitised and on open access through the Australian Joint Copying Project.

British Newspaper Archive.

Census records and parish registers.

Laing, Alexander. Memoirs of Alexander Laing. Transcription produced by Robert Tanner. Historical Society of the Municipality of Sorell. 2019. Sorell, Tasmania.

Lawrence, William. The Autobiography of Sergeant William Lawrence. A Hero of the Peninsula and Waterloo Campaigns. Edited by George Nugent Bankes. Samson Low, Marston, Searle and Rivington. 1886 London. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/29263/29263-h/29263-h.htm#page194

National Library of Australia – online digitised newspapers (Trove website).

Smythies, R. H. Raymond. Historical Records of the 40th (2nd Somersetshire) Regiment. 1894. Devonport UK. https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=MvT-O4I0xjAC&pg=PA200&source=gbs_toc_r&cad=2#v=onepage&q&f=false

Waterloo Medal Roll. 1815. The National Archives. MINT 16/112. It has been digitised and can be seen online at Ancestry.com and on the Royal Mint Museum website. The latter includes supplementary pages of additional names relating to late claims and replacements.

[1] Obituary for Captain Robert Phillips – Perthshire Advertiser 09 Nov 1843, Paisley Advertiser 04 Nov 1843.

[2] British army. WO 12. Muster rolls and pay lists of the 40th Regiment. The National Archives. The pay list for the 4th Quarter 1823 has a notation that George was on board the ship Prince Regent.

[3] The Sydney Gazette 22 July 1824

[4] Hobart Town Courier 5 Jan 1828. The items stolen were three tablecloths, two silver spoons, three knives and forks, one new bed-tick, four pair of blankets, one lady’s plaid riding habit with black skirt, sundry articles of wearing apparel consisting of stockings, a shirts, a black coat and three pairs of trousers, one brass bound dressing case, one percussion fowling piece, one double-barrelled gun, two bags of shot, one canister of gunpowder, powder flask, tinder-box, flint and steel.

[5] Hobart Town Courier 26 Jan 1828

[6] The Tasmanian 15 February 1828

[7] The following is a list of the articles found in Pearson’s possession:

One black horse, two blankets, one ditto marked N with a figure 3 under it, 40 lbs flour, one canvas bag, one percussion fowling-piece, one half sheep shears, one old copper tea kettle, one striped bed-tick, two coloured shirts, two white ditto (one marked G Kemp 3), two pair blue trousers, two pair white ditto, one pair jockey boots, one black cloth waistcoat, one velveteen jacket, one white vest, one Fustian shooting jacket, one tablecloth, one duck frock (probably frock coat), one tartan riding skirt, one pair half boots, one powder flask (for storing gunpowder), one pair gloves, one pair cotton stockings, one kangaroo pouch with 19 rounds of ammunition.

[8] Memoirs of Alexander Laing.

[9] British army WO 12 pay lists of the 40th Regiment. The National Archives. Pte David received extra pay at the end of the June 1828 quarter for the first time, but it doesn’t state how much.

[10] British Army. WO 12/5340 refers to the volume containing the 40th regiment January 1829 pay list which gives George David’s date of arrival in Bombay as 21 January 1829, which was also the date of arrival of the Phoenix.

[11] Smythies, R. H. Raymond. Historical Records of the 40th Regiment, page 229.

[12] British Army WO 12/5340 40th Regiment pay list February 1829.

[13] Devon and Somerset News 15 June 1876

[14] Western Gazette 21 June 1878

[15] Exmouth Journal, 1 April 1882

[16] Devon and Somerset News 22 June 1882

[17] Devon and Somerset News 15 February 1883

[18] Devon and Somerset News 8 May 1884

[19] Devon and Somerset News 15 May 1884

[20] Devon and Somerset News 19 June 1884