Gunner, Tank Corps

The Following account of Gunner Charles Edward Bond has been kindly sent to us by Stephen Pope, Principal Researcher of the First Tank Crews Project, which is looking into the life stories of those who crewed the first tanks in September 1916. If you might be able to help with details of Charles' life, especially with a photograph, they would be very keen to hear from you, or, of course, contact us at the link at the bottom of the page. Additional material from the Bridgwater Mercury has been supplied by Joyce Hurford.

Although Charles is buried in a simple kerb plot with his parents and has no Commonwealth memorial, and no inscription records his war work, he is included in the 'those buried in the cemetery who fought and died' section as he died as a direct result of his service.

13 September 1888 - 10 September 1918

Charles Bond's name is recorded on the Bridgewater War Memorial as he had served with the Tank Corps in the Great War. His story is not however known - in fact, he served in the first ever tank action on 15 September 1916 on the Somme battlefield near the village of Flers

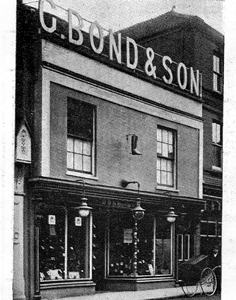

Charles was the youngest son of a Bridgwater boot and shoe manufacturer George Elias Bond and his wife Emily. Charles, who was bought up at Gordon Villa on the Taunton Road, had two elder brothers and three elder sisters. Unlike his eldest brother William, who took over the family firm when his parents died in the summer of 1909, Charles was involved in the jewellery retail business. He initially worked in Cardiff and then moved to Bournemouth where he worked as a shop manager.

When the Great War broke up, Charles did not immediately volunteer but enlisted in 11 December 1915 as conscription was being introduced. A keen motorcyclist, Charles wanted to become a motor cycle despatch rider but, at the time, there were few vacancies. However, in February, the Motor Machine Gun Corps (MGC) were looking for people like Charles and he volunteered to join them. On 10 March 1916, he passed the mandatory trade skills test at Coventry and was sent to Bisley for initial training.

Around this same time, Armoured Fighting Vehicles (AFV) were being secretly developed. Their role was to support British infantry units by flattening German barbed-wire obstacles, neutralizing defended trench systems and most important of all, destroying machine gun positions. Each AFV needed a crew with proven mechanical and machine- gun handling expertise which was rare amongst the British Army. However, those at Motor MGC Training Depot had just the right skills and the first six tank companies were formed at Bisley in late May 1916. To ensure the purpose of the new units was hidden, these companies were called the Heavy Section MGC and the AFV became known as tanks.

The British Commander in Chief, General Douglas Haig, had been keen to deploy tanks as quickly as possible. Tank training was not however possible in the area around Bisley so the tank companies moved to a rural estate near Thetford where a secret training location had been established. The first tanks started to roll off the production line in June and, by the end of August, there were sufficient for two companies of tanks, each with twenty four tanks, to deploy to France.

There were two tank variants; the male was fitted with two cannons which fired a 6 pound shell capable to destroying machine gun posts whilst the female was designed to kill men using four belt fed machine guns. Each tank crew consisted of eight men, the commander or "Skipper" was a junior officer, four gunners operated the weapons and two gearsmen who maintained the gearboxes, selected the range at the instruction of the driver and provided ammunition to the gunners. An Army Service Corps (ASC) unit provided the drivers but these were not initially integrated with the crew although this changed in 1917.

On 25 August, Charles deployed with the six tanks of No 2 Section of D Company Heavy Section MGC. He sailed on the SS Ilston from Avonmouth to Le Havre where the tanks were unloaded. Two days later, they moved at another training area near Abbeville where the tanks and their crews undertook final firing practices. They also provided demonstrations to senior officers so that these could understand the advantages and limitations offered by the tanks. Douglas Haig had directed that the tanks were to support the next major offensive on the Somme battlefield which was to start of 15 September. Charles and his crewmates arrived near the Somme on 10 September and undertook final preparations before deploying forward on 13 September.

On 15 September Charles was a member of tank crew D15 which manned the female tank no 537 which was built at Oldbury near Birmingham. Charles' crew consisted of the skipper, Lieutenant Jack Bagshaw from Uttoxeter, Lance Corporal (LCpl) Charley Jung from Southampton with Cyril Coles from Poole, Charles Hoban from Warwick, Arthur Smith whose home town is unknown, and "Tippo" Wilson from Grasmere. Pte Albert Rowe, an ASC soldier from London, was tasked to drive but may not have done so. Their tank was one of ten were tasked to support the 41st Division attack on Flers, the most heavily fortified village in the area.

We are lucky that a first-hand account exists in which Charles describes the action from the time they left their start point at 6.15 a.m.

We crossed the (British) Line to the left (west) of DELVILLE WOOD. On approaching the enemy front line of trenches, we were met with very hot fire. Our prisms (vision devices) were smashed within few minutes, the glass getting into my eyes made it very difficult for me to detect exactly what was going on. A bullet struck the corner of the car (tank) between the Vickers gun and the (armoured) plate and went through my sleeve without touching my arm.

Immediately after this, I was knocked over by a piece of shrapnel or splinter from a HE (high explosive shell) hitting me under the shoulder and thigh. We could not determine where it went through (the side of the tank). I continued to fire my gun which was the left hand front and then a piece of shrapnel hit Mr Bagshaw's prism and igniting the lining to the shutter. Mr Bagshaw had his face cut to pieces as did the driver L/Cpl Jung, the latter's face bleeding badly. I then began to feel the effects of my wounds and asked Gnr Smith to take my place. Before many minutes gunner Smith was wounded through the forearm and Gnr Hoban was also badly wounded.

We were still advancing under increasing fire which was very hot when a shell pitched through the front putting the car out of action. At about this time Mr Bagshaw was wounded in the arm. We looked out to see if anyone was near us but could not see anyone. Soon after the infantry passed us and we were all ordered by Mr Bagshaw to jump out. We found that Gunner Wilson had been badly wounded in the leg. I left the car after taking over Gnr Coles' gun whilst the others got out except Mr Bagshaw and L/Cpl Jung. On getting out I saw that Coles had been shot through the head- evidently by snipers - and getting to the back of the car saw Gnr Wilson badly wounded in the leg and unconscious, and the ASC driver who appeared to be suffering from shock.

We tried to get some help to Wilson but the shelling was to too much to expose oneself very much. Mr Bagshaw and L/Cpl Jung went to see who was safe and on consideration I decided to try to get the R.A.M.C. to bandage Wilson's leg which was bleeding badly. I saw Mr Bagshaw dive into a shell hole to try to help some wounded fellow so immediately decided get to the R.A.M.C who were coming across the battlefield.

A shell burst a few yards away and completely covered me. Having dug myself out, I proceeded to the trenches previously occupied by the New Zealanders, and there met a N.Z. officer who had been shot in the back. After attending to him until (soldiers wearing) the Red Cross arrived, he made them carry me with him to the nearest dressing station. I was attended to there and then sent to another station where they inoculated me and sent me to the Camp Hospital at ESBART. I asked to be allowed to enable on the following Wednesday 20th instant. They took me by car to ALBERT, from there I walked and rode to the LOOP (the main tank base between Fricourt and Bray sue Somme) at 5.30 p.m. reporting to QMS (Quartermaster Sergeant Edward) Williams. Since then I had have my wound dressed by the camp doctor.

This report, with two others recorded in the D Company correspondence book, was made on 29 September. Charles' tank was repaired and recovered to the Loop by 1 October but Charles was not to see battle again.

Charles wrote his own account of the first battle for the Morgonian, which was later published in the Bridgwater Mercury on 25 July 1917:

It was in her Majesty's land ship 'Duchess', or 'Willie' as we called her, that crossed into No Man's Land on 15 September 1916. Our departure from England and the journey to our specially constructed camp I shall never forget. The first stopping place behind the Somme was Yvrench where we gave the peasants a nasty shock by entering suddenly with 50 of these queer monsters. However by the time Colonel Solomon and his staff of artists had altered the battle like appearance of a future ichthyosaurus those good folks had become as familiar with us as the Hun are now.

We were guarded all the way by the famous Bengal Lancers whose horse marching and manoeuvres filled us with admiration. We then proceeded to our camp which overlooked the whole of the Somme district. We often thought the enemy must have learned of our arrival as we were subjected to raids every night. Having tested the guns and having all the ammunition on board we set out at 5.00 pm in the evening of the 14 September in single file to a dump one and half miles from our foremost line of defence.

We passed the camps of the Guards divisions (Life, Scots, Irish and Coldstream) who were going into action with us. This caused tremendous excitement because it was the first time they had seen our 'buses'. At 12 that night we covered the tanks with netting and leaves and went to sleep as best we could.

Early the next morning the officer laid a tape from the dump picking out the most suitable path for the tanks to proceed over. We spent the rest of the day getting in stock of everything we might require for our joy ride to the Rhine. We had joints of meat and sardines and the favourite, pork and beans, stewed peaches and apricots, bread, butter and jam, sugar and milk with wine and other fluids to warm us up.

The 'Duke', our leading tank broke down just when it was wanted, and word was passed around that we were to lead into action and carry out the objective alone. At 5.30 in the morning of the 15 we crossed the first line of British trenches and they cheered us as vociferously as if their pet team had scored the winning goal. It was a misty morning when at 6.00am on the dot the 'Duchess' set out across No Man's Land.

What an awakening the enemy must have had as they heard the buzzing of the engines and saw those queer forms emerging from the greyness. Of course they greeted us with a hail storm of bullets and bombs which rattled against our steel walls. Our artillery was marvellous and the enemy was so scared they either jumped over the parapets and surrendered or made for their second line, thus affording us a target that, after one and half hours of firing, the ground was a mass of dead soldiers.

We suffered pretty badly ourselves. I was wounded twice and No 2 and No 5 caught bullets in the side. No 3 had his leg severed at the knee and died in hospital. We were just on the edge of our objective when a shell hit us full in the face, knocking out the driver and our officer. I immediately jumped into the driving seat but it was no good the 'Duchess' was grounded.

We were ordered to get out with the machine guns and back up the infantry, who were fighting magnificently. After six hours in the trenches, my officer badly wounded and my own wounds making themselves felt, we groped our way back, managing to help along others who were worse off than ourselves. I just remember hearing a heavy shell pitch near me and then came a void until I found myself in the hands of a doctor. On return to my unit only three of the crew were alive.

By 4 October I was on the warpath again when I contracted trench fever. The medical officer was Mr V H Coates, well known to Somerset footballers. We had several talks together about Bridgwater and its boys but in the end I was labelled 'Blighty' where I was once more in training and expecting to be on the move ere long.

Of the other crewmen, Jack Bagshaw was evacuated to London and, once recovered from his injuries, fought at Ypres in the summer of 1917 and at the Battle of Cambrai in November. Jack survived the war as did Charley Jung who made a full recovery from his wounds, remaining with D Battalion Heavy Branch MGC then 4th Battalion Tank Corps until the end of the war. Charles Hoban died of his wounds on 15 September and was buried near to the tank. Hoban's grave was subsequently lost but Cyril Coles' body was well marked and is now at the Bulls Road cemetery near Flers. "Tippo" Wilson died of his wounds on 22 September 1916 and is buried at the Heilly Road cemetery. Arthur Smith recovered from his wounds and served with the tanks for the rest of the war. After Albert Rowe recovered in England, he left the ASC and, in July 1917, returned to France serving with the Tank Corps for the rest of the war.

The field conditions in which soldiers lived on the French battlefields caused many to become ill. Charles caught trench fever and was evacuated to England in October. He was treated at the City of London Military Hospital for over a month before being sent for convalescence to Eastbourne. On 21 December, he was released from hospital and, after Christmas and New Year's leave, was sent to Bovington where the tank training centre was being established. Charles was posted to the newly formed G Battalion on 8 January 1917 where his operational experience was most welcome. Charles was not, however, fully recovered and in early March was posted to the Tank Depot Battalion near Wareham. Five months later, Charles was examined by a Medical Board which determined that he had TB, having suffered from measles, and they recommended he be treated in a sanatorium.

On 13 September 1917, coincidentally his 29th birthday, Charles was discharged from the Army as he was "no longer physically fit for war service". He returned home to Bridgwater and initially lived at "Spark Hayes" on the Taunton Road. Despite further medical treatment, he did not recover from TB and died just before his 30th birthday on 10 September 1918 at his brother's house in Wembdon.

From the Bridgwater Mercury 16 September 1918:

Death of Mr C Bond former Gunner and Tank Corp.

His many friends learnt with deep regret of the death, on Tuesday, at the Laurels, Wembdon (the residence of his brother Mr G. Bond) of Charles Edward Bond, formerly a gunner in the tank corp. He was 29 years of age and unmarried and was educated at Dr Morgans School. He joined the army two ago and was one of the crew of the first tanks to raid the enemy lines in France. On that memorable occasion he was twice wounded and was invalided home receiving treatment at a London hospital. Soon after his return to France he contracted trench fever and was invalided home for the second time. Measles and other complications followed and tuberculosis symptoms appeared. He was granted a discharge and recently he had been staying on the Quantock Hills but his condition gradually got worse and a heart attack ended his life on Tuesday The funeral took place at Wembdon Road cemetery officiating Rev. Langham (St Mary) and W. Catlow, Head Master of dr. Morgans School

Charles was buried at nearby cemetery on 13 September, the day which would have been his 30th birthday. His death, previous Army service and wounding was reported in the Bridgwater Mercury. His service was recognised by the local authorities as he is listed on the Bridgwater war memorial.