Sunday 25th May 2014

Before I start just a reminder to tread carefully when walking through this site and be ever respectful to the dead. Hello and welcome to the Wembdon Road Cemetery. Today we will be walking through this burial ground and talking about some of those individuals commemorated here. Today we will be talking about the First World War, the Great War, that of 1914 to 1918. There are many war memorials in the Wembdon Road Cemetery ranging from the Indian Mutiny of 1857 through to the Korean War a hundred years later, but by far the most numerous amongst them belong to the Great War, a conflict which had more impact upon our town than perhaps any other. Twenty seven service men are buried here in the cemetery, and each of them have the white commonwealth memorial, but a further twenty one men are commemorated here, mentioned on the family memorial, but whose bodies are buried to lie forever near the battlefields on which they fell. There are also countless more interred here who served in the conflict but survived and many families would have lost sons and brothers who are not recorded here. It is safe to say that the war would have impacted upon every single person buried in this cemetery who was alive at the time. These white memorials therefore do not stand in isolation, but stand amongst their community and families.

The impact on the town was severe. I'll be talking about the individuals, their lives, but also the war and its impact on the town. I do not have the time to talk about every poor soul commemorated here and if you would like help with research or have stories to tell yourself do not hesitate to get in contact via the website. Please note as we walk around the poppy markers given by Mr. Allan from the Bridgwater British Legion and also note the living poppies, donated by the cooperative funeral care.

Memorial 1 James Cook

We start here with the most impressive memorial in the cemetery, not to a soldier, but to the old Town Clerk, James Cook. Before the war Bridgwater was a wealthy town; the brick and tile works employed hundreds of men, the river, canal and railway bought commerce and trade with the rest of the country and the rest of the world, and the fertile land around the town was rich and productive. This memorial neatly sums up Bridgwater before the war, prosperous, proud and ambitious. This confident world summarised by this memorial would be forever ended with that war. This becomes clear if we look at the commemoration of individuals; this sort of bold statement of the achievements in life would give way to to these low and humble kerb memorials. After the war any memorials of the sort of ambition shown on the Cook memorial would no longer be commissioned for individuals, this sort of structure would instead be the precursor and model for many of the cenotaphs, communal war memorials, which can be found in every city, town and village within these kingdoms. Which is the reason why this particular memorial is listed and why I mention it today.

On 4 August 1914 Britain declared war on Germany. The Bridgwater Squadron of the West Somerset Yeomanry was mobilised and over 150 horses in the town and surrounding area were bought up for military purposes. The GWR bridge at Dunwear was put under guard day and night and countless young men enlisted to see the world and fight the foe. Because of this, by 1915 it was noted that the population in Bridgwater had fallen sharply and so the townswomen entered into the workforce in the shirt factories making kit for the soldiers. That so many women were working was (incorrectly) blamed on a tragic jump in infant mortality in the town in 1917. Although I will be talking more or less exclusively about men today do bear in mind the impact the war had on everyone. The men might be killed but the women and children had to live with this loss for the rest of their lives.

Memorial 2 Walter Roman

If you look there you will see the grave of Walter 'Rattler' Roman, who grew up in West Street. He had a wonderful career and was something of a national name, but his life was cut tragically short by the war. At the age of 13 he joined the Bridgwater Dreadnoughts, the local rugby team, and proved himself very talented, to the point that at the age of seventeen he was playing for Somerset. Two years later he joined the army and had a distinguished career fighting in the Boar War, thereafter serving in India for five years. The Boar War was a bloody and hard won affair, and was almost a disaster for the British, its use of modern weapons was the precursor of the war to follow. But Walter survived.

In 1907 he left the army and returned to Bridgwater. He worked in the brickyards but returned to Rugby and managed to go professional and signed for Rochdale, where he also opened a pub. In 1914 he was playing for England. However his career was halted in its renaissance by the war. As a reservist he was recalled by the army. On his birthday, the first of July 1916, the first day of the Battle of the Somme, his unit went over the top of their trench into no-mans land and advanced towards the German positions. While charging forward Walter was savagely wounded down one side. He was dragged from the battlefield to safety and quickly bought to back to Britain, but he soon died from his fatal injuries. His body was bought back to Bridgwater and his funeral was held in a tightly packed service in Holy Trinity near the Broadway. Throngs of people lined the streets between the church and here, and the procession took a long time to reach his grave, such was the outpouring of grief at the loss of this famous individual.

The Somme cost a total of 623,907, British French and Empire troops, and between four to five hundred thousand German men. To put that in perspective the total number killed in the battle is more than the entire population of Somerset now.

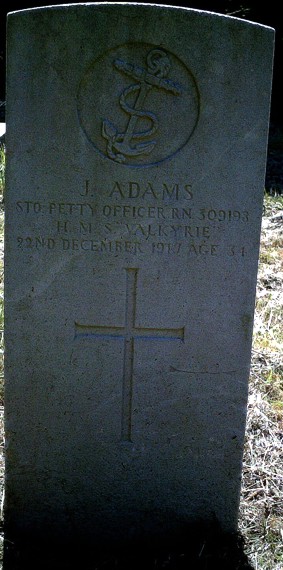

Memorial 3 James Adams

The war carried on at sea as it did at land, and there are two naval personnel buried in this Cemetery. The was only one huge naval battle in the war, the Battle of Jutland, but there were many smaller and bitter clashes and skirmishes, between ships, craft and submarines. It must be remembered that the German U-Boat campaign of this war came as close if not closer to starving Britain than that of the second and this was the real reason for the jump in infant mortality in Bridgwater in 1917. Bridgwater is the town of Admiral Blake and had and still has a strong maritime heritage. James Adams was born in 1883 at Huntworth and lived in 4 Halesleigh Road. He had a wife Eliza Emma Adams of Hamp. He joined the Navy before the war and in 1914 at the Battle of the Falklands he was serving as chief stoker on the HMS Cornwall. In June 1917 he was assigned to a brand new destroyer, the HMS Valkyrie, upon her completion. However only half a year later in the December that year he was killed in an explosion when the Valkyrie hit a sea mine. He was aged just thirty four. His body was returned to Bridgwater and buried here. The Valkyrie survived and remained in service in the Royal Navy until 1936.

Memorial 4 Willcox

Company Sergeant Major Charles Willcox buried over there is worth a mention. He was from Johannesburg in South Africa to a Bridgwater family and actually survived the war. He was constantly mentioned in despatches for his bravery. In 1914 he survived a shell blast which tore the kit off of his back, the same year he was wounded by shrapnel through his lung. He was given many medals for his bravery. However he was accidentally killed on the 4 December 1919 in a boxing match at the National Sporting Club in London, aged just 26. One of his honours was the Russian Order of St George, 4th Class, Russia's highest award for bravery in defending Russia, awarded for his bravery in the trenches.

Russia was of course one of the great losers of the war, having suffered staggering casualties, food shortages and civil strife it descended into Civil War and Revolution, the outcome being the murder of her Tzar and royal family and the rise of Communism and many decades of brutality. It is important this year not to just remember our own, but everyone who suffered in this war. Far too much of the media attention is focused on the British effort and the defeat of Germany, but fails to mention the horrors in Russia, the deprivation and collapse of the Hapsburg Empire, the brutal final days of the Ottoman Empire and the very valiant and heroic effort by France which almost bled herself white. All humans suffer the same and die the same.

Memorial 5 Cecil Bowerman

This is the grave of Cecil Bowerman. I'm pleased to say that the Friends of the Wembdon Road Cemetery have restored this memorial this year. At the outbreak of the war, aged just seventeen he joined the North Somerset Yeomanry as a second Lieutenant, and was the youngest commissioned officer in the British Army. He worked his way up the ranks and transferred to the Royal Engineers. He was awarded the Belgium Cross of War for his distinguished service and survived the war, having served on the Western Front all the way from start to finish. In this respect he was a very lucky man, few could claim that; but it was more of a curse. His is an example, no doubt like many other men buried in this cemetery who went off to fight and who one day came back. But just because they had no physical scars does not mean that they weren't affected by it. The horrors of war would stay with them until the day they died and poor Cecil here would take his life in a fit of depression in 1935. He was a victim to the war long after the guns had fallen silent.

Memorial 6 Arthur Oswald Major

This is the memorial of Captain Arthur Oswald Major. We can forget sometimes that the war carried on far beyond the trenches in Flanders and one of the major theatres was in the Middle East. Arthur was born in Bridgwater in 1875. In 1881 the family lived in Haygrove and his father owned a Brick and Tile works which at the time employed 120 men and 100 boys. By 1901 Arthur had joined his father's firm as a clerk and lived at home at 9 Northfields. By 1911 Arthur was working as a cashier in the firm and he still lived with his parents. He joined the army at the start of the war and through his abilities rose from private all the way to captain.

The Battle of El-Gib recorded on his memorial is now known as simply part of General Allenby's wider Battle for Jerusalem in November 1917. On 21st November, Allenby's 75th Division had been held up by hostile artillery fire. Orders were given for the Wiltshire Regiment and the Somerset Light Infantry to attack and capture El Jib and Bir Nebala. On 22nd November, they moved forward with a squadron of cavalry, the Somersets at the front of the attack under the command of Captain Major. A mistake on the first day held up the attack and the men had to endure a cold night camping in their warm-weather tropical kit. The following morning they attacked El Jib, and immediately came under severe shrapnel and high explosive fire, without the benefit of their own counter-artillery. The Somerset men nevertheless moved forward under intense machine gun fire. Captain Oswald Major, who went forward with his company, was first wounded and then killed outright by shellfire. Small groups of his men reached the village, but all perished. His battalion lost 69 killed and over 400 wounded in the unsuccessful attack. However by the start of December Jerusalem was successfully captured from the Turks.

Arthur was 42 when he died and there is no record of him having married. He was laid to rest on the Mount of Olives outside of Jerusalem, and this memorial records how for him to have been buried in such a holy place was a consolation for the family. In the entire attack on Jerusalem 18000 British and Empire men were lost and 25000 Ottoman forces.

Memorial 7 Harry Seward

We now move on to another theatre of War: Africa. Harry Seward was born in Bridgwater in 1882, and his family lived in 14 Angel Crescent, his father being a shop assistant. In 1901 he was living in Hornsea in Middlesex with his older brother, working as a builder's surveyor. Harry fought and was killed at the battle of Latema-Reata in March 1916, when British forces advanced from what is now Kenya into the German colony of Tanzania. Although the battle was a Commonwealth victory, during the fighting a machine gun post of The Rhodesia Regiment came under heavy German fire from three sides. In his gun pit poor Seward was wounded in this assault. He was dragged to safety by Private Harold Evans, who then returned to the pit and prevent a rush attack behind the British lines, and his bravery contributed to the winning of the battle and won him the Distinguished Conduct Medal. However, although rescued from immediate danger, Seward was so badly wounded that he died not long afterwards. He was buried there in Tanzania. His grieving siblings added his name to the family memorial where his parents had previously been laid to rest. Two hundred and seventy men were killed in the battle.

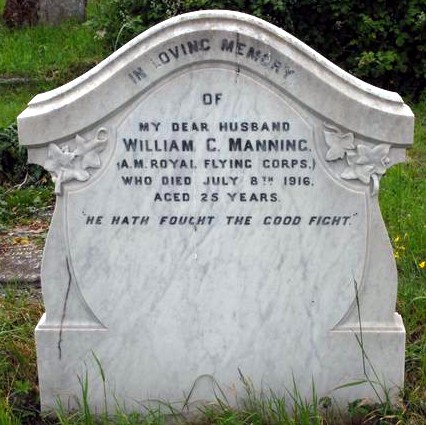

Memorial 8 William Manning

We now move on to a completely new theatre of war; the air. William Charles Manning was born in 1891 and in 1911 he lived at 21 Polden Street and worked as a cabinet maker, living with his six siblings. He married Nellie Frances Dodden, of Reading in 1915. Near the start of the war he enlisted in the Royal Flying Corps, the forerunner of the RAF, and served as Air Mechanic second class, which meant he was the lowest rank of pilot, the rank later being renamed as aircraftman. Aeroplanes were first used simply for reconnaissance over the troops, but were quickly adapted to attack ground positions and then each other. William was sadly killed in Britain on the 8th July 1916 in a flying accident. This was during the first week of the Battle of the Somme and the Flying Corps was desperate to gets planes and crew to the front as soon as possible, and in the rush accidents were made. By the end of the Somme offensive in November 1916, the Royal Flying Corps had lost 800 aircraft and 252 airmen killed.

War in the air was a terrifying new prospect. This is quite evident as Bridgwater went as far as insuring St. Mary's Church against damage by enemy aircraft, for the grand sum of 23000 pounds in 1916.

Memorial 9 David Pole

After aeroplanes now we turn to another new technology, the Tank. David Pole was born in 1892 in Bridgwater to Thomas and Eliza Pole. In 1901 his family lived in Saltlands House, his father was a brickyard foreman. In 1911 David lived with his older brother coalminer Thomas Pole in Merthyr Tydfil in Glamorgan, working as a Collier Boy. In the war he served in the Grenadier Guards. He was killed in the battle of Cambrai in the winter of 1917. He was an infantry man, but I mention tanks here as this was one of the first tank battles. Although tanks had been used in combat earlier in the war, this was when they were first used en masse by British forces. Their use with new artillery techniques completely broke the German lines in what should have been a stunning victory. The first days successes were so astounding that church bells were rung out across Britain in celebration. However the attack was not properly reinforced and the Germans quickly counter attacked and with such ferocity that almost all the hard won territory was again lost. David's unit had managed to fight their way into a French village but on arrival met a strong and determined Germans counter attack and were forced to withdraw, during which time David was killed in action. The British and Empire losses in the battle were around 44,000 while the German losses amounted to around 45,000.

Tanks were another new development in this war, but failed to be a war winning machine. They were very popular though and did wonders for moral. In 1919 Bridgwater was awarded a tank, which was placed by the station in St. John Street, in return for the vast amount of money raised by the townsfolk in warbonds. It's not there today as it was taken away in the Second World War for scrap.

Victor Pitman was born in 1898, the son of Tom and Elizabeth Pitman. In 1911 aged 13 he had a job as an errand boy and lived with his family in 17 Blacklands, with seven siblings, supported by his father the corporation weighman. He was a private in the Gloucester Regiment and was killed in the Gallipoli campaign in modern day Turkey. The attempt to knock the Ottoman Empire out of the war, by sailing and capturing Constantinople was a complete shambles and military disaster. Falling short of their target, the allied forces made landfall in the Dardanells. However the British, French and Empire forces could not make headway from their beachhead and were pinned down by the Turks. Thereafter followed a futile and bloody struggle in the heat of the sun. Victor managed to survive the bulk of the campaign up to the point that it was abandoned and the withdrawal was started. A blizzard struck in early December and then rain flooded trenches and drowned soldiers then the following snow killed more men from exposure. Victor died within this horror. British, French and Empire losses amounted to 252,000. Ottoman losses were around 251,000.

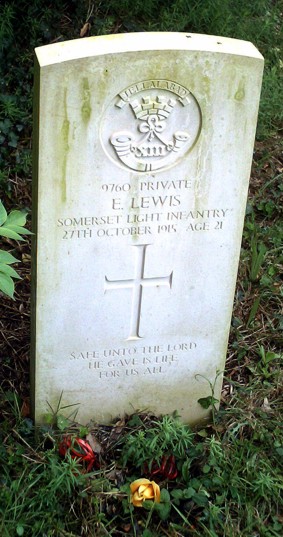

Memorial 11 Ernest Lewis

We will stop briefly with two memorials which bring home the impact of the conflict. This first reads; 9760 Private E Lewis Somerset Light Infantry 27th October 1915 aged 21. Safe unto the lord he gave his life for us all. Ernest Lewis was the 21 year old son of Frederick Lewis, of Gloucester Place, Friarn Street, Bridgwater, Bridgwater. He died at the first battle of Ypres and was one of the first victims of deadly gas poisoning. He was bought back to the Bridgwater Hospital, but died on 27 October 1915. He had three brothers who served in the war and all three would be badly wounded at the Somme in the following year. The line 'he gave his life for us all' is of course true of all the men commemorated here.

I mention this and the next memorial for their respective messages. This first reminds us of our duty to remember the dead, he gave his life for us. The second memorial is much more personal and reminds of the human tragedy of the war, over here.

This reads 1073 9460 Guardsman JR Steadman, Coldstream guards 1st November 1917 aged 26. Friends are friends when they prove true but I lost my best friend when I lost you. Joseph Richard Steadman was born in Chester. He died of wounds 1st November 1917. He was the 26 year old son of Alfred Steadman, of Birmingham and husband of Ethel May Westgate of Bridgwater. This is a crushingly sad poem and better than anything else I could show you summarises the horrible personal tragedy that was the loss of all this life.

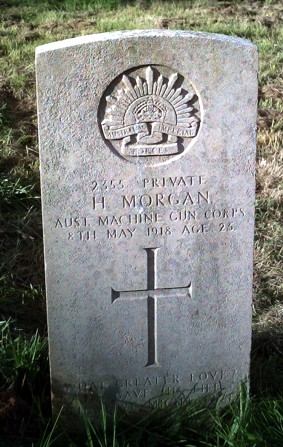

Memorial 13 Henry Morgan

This is the memorial of Henry Morgan. He was the son of Charles and Ellen Morgan, of 2 Hampton Terrace, Bridgwater. In 1911 he lived with his parents in Haygrove and was learning to be a farmer, his father was the manager in the Collar factory in town. By the age of 22 he had put his education to use and was a living as a farmer in Australia, New South Wales. He enlisted on 18 May 1916 and embarked from Sydney in October, becoming a private in the Australian Machine Gun Corps. He died from Gas poisoning on 8 May 1918. This was during the Great German offensive of March to July 1918, a bid on their part to deliver a knockout blow to the allies before America could properly enter the war. Thanks to the sacrifice of the likes of Morgan the German offensive was eventually ground down in to a bloody halt, which finally broke the German war machine, which was countered and pushed back beyond its original lines. The stalemate of the trenches was broken and in a hundred days the German army was routed, which would bring an end to the war.

In this cemetery are a couple of men serving in Australian units as well as Canadian ones, from both world wars. Britain and France were not alone in their efforts and both could draw on their respective empires. Bridgwater was connected to all sorts of families in South Africa, Canada, Australia and New Zealand who fought in the war and this reminds us of the effort of all the commonwealth forces, African, Indian, Pakistani, Caribbean and so forth. All would sacrifice brave men for the cause of Britain. The very face of Britain would also change. It's generally felt now thought that if Scotland goes independent this year it will be the end of the Union, but the Union was first broken as a result of the First World War when Ireland left and set itself up as a republic. The whole of Europe was transformed by the war and so were we.

Memorial 14 Roland Roberts

Roland Roberts was born in 1896 in Clevedon. He was a private in the 2nd Battalion Coldstream Guards. I bring you to this memorial last because of the date he died. The 10th November 1918. The war ended the next day. He never saw peace. To compound this tragedy, he had married Gladys Laura Pyne earlier that year, who was now left a widow. He probably died of the influenza epidemic, which hit Britain at the end of the war and carried off countless numbers of the population. A large number of people in the town died in the epidemic and lie at rest here.

The total killed in the war on all sides was around ten million. That's roughly the population of the whole of Greater London today, or twice the population of Scotland or New Zealand or Ireland, ten times the population of Somerset. On top of this the total injured amounted to some twenty million, with a further ten million unaccounted for. If you imagined the entire population of this island wiped out that the sort of numbers we are dealing with. In 1918 the Town's Roll of Honour recorded some 308 men belonging to the borough who had fallen in action. The servicemen here were given Commonwealth War Graves, which have been maintained to this day. In 1924 the War Memorial was erected in King Square in their memory. The same year as the Museum was founded. If we could now spare a moment to remember the fallen. We will remember them.